A Majority of Westerners Are Dissatisfied With Democracy — and That’s Okay

What the data shows

Yesterday, at the Southern Economic Association, I met with Doug Norton program director of the Philosophy, Politics, and Economics program at Florida State University and Branch Head for Economic Liberty Institute for Governance and Civics. We talked about the “loss of hope and its impact on capitalism and democracy” and how critical it is for us to tackle despair. The conversation was filmed for release by Doug and his team for educational purposes.

Two hours later, Glenn Blomquist, president of the SEA and emeritus professor of economics at the University of Kentucky, gave his presidential address titled “Benefits, Costs, and the Size of the Pie: An Economist’s Musings….” His presentation centered around Americans’ loss of trust in their institutions over the past 50 years.

Both of those discussions reminded me of a column Antowan Batts wrote for Decode Econ, focusing on the increased dissatisfaction with Democracy and how to make sense of it.

So let’s discuss what’s happening with democracy.

-Abdullah Al Bahrani

How can widespread dissatisfaction with democracy possibly be “okay”? Simple, because dissatisfaction isn’t the same as rejection. In fact, the latest data shows a more nuanced story: people still value democracy deeply, but they feel it’s under-delivering. And that gap between expectation and reality is exactly where modern democracies need to focus their attention.

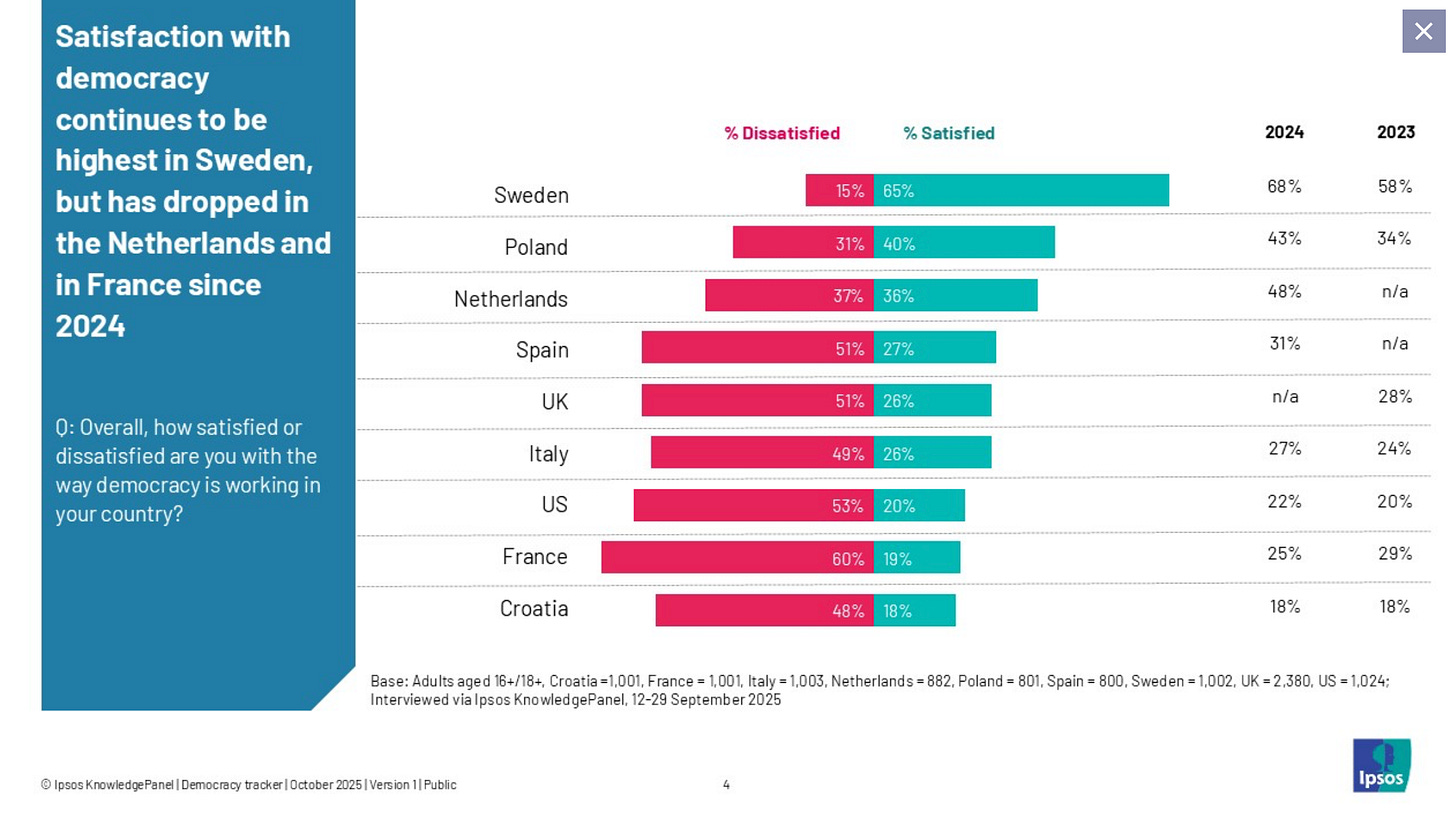

Recently, Ipsos released its State of Democracy 2025 survey, a sweeping look across Western nations that reveals something both troubling and oddly hopeful. Yes, large shares of citizens in Western democracies are unhappy with how democracy is functioning. But no, they are not giving up on the democratic idea itself. Most still support democracy, still believe it is the best system, and still want it strengthened rather than replaced.

This tension between dissatisfaction and commitment tells us far more about our political moment than panic or cynicism can.

What the Numbers Say: A Deep Trust Problem

According to the Ipsos data, satisfaction with how democracy works is shockingly low across most of the Western world. In eight out of nine Western countries surveyed, fewer than half of respondents say they are satisfied with democracy in practice. The United States and France are near the bottom, with satisfaction dipping to around 20%. Even high-functioning democracies like the Netherlands and Germany show rising frustration.

Sweden is the exception; roughly two-thirds of Swedes say they are satisfied with how their democracy functions. Its stability, trust in institutions, and strong social protections buffer it from many pressures facing its neighbors.

So why the discontent elsewhere?

The survey identifies several key drivers:

Perceived lack of accountability

Many citizens feel politicians and public institutions are out of touch, unresponsive, or shielded from consequences. When people see rules applied unevenly, one standard for elites, another for everyone else, trust evaporates.

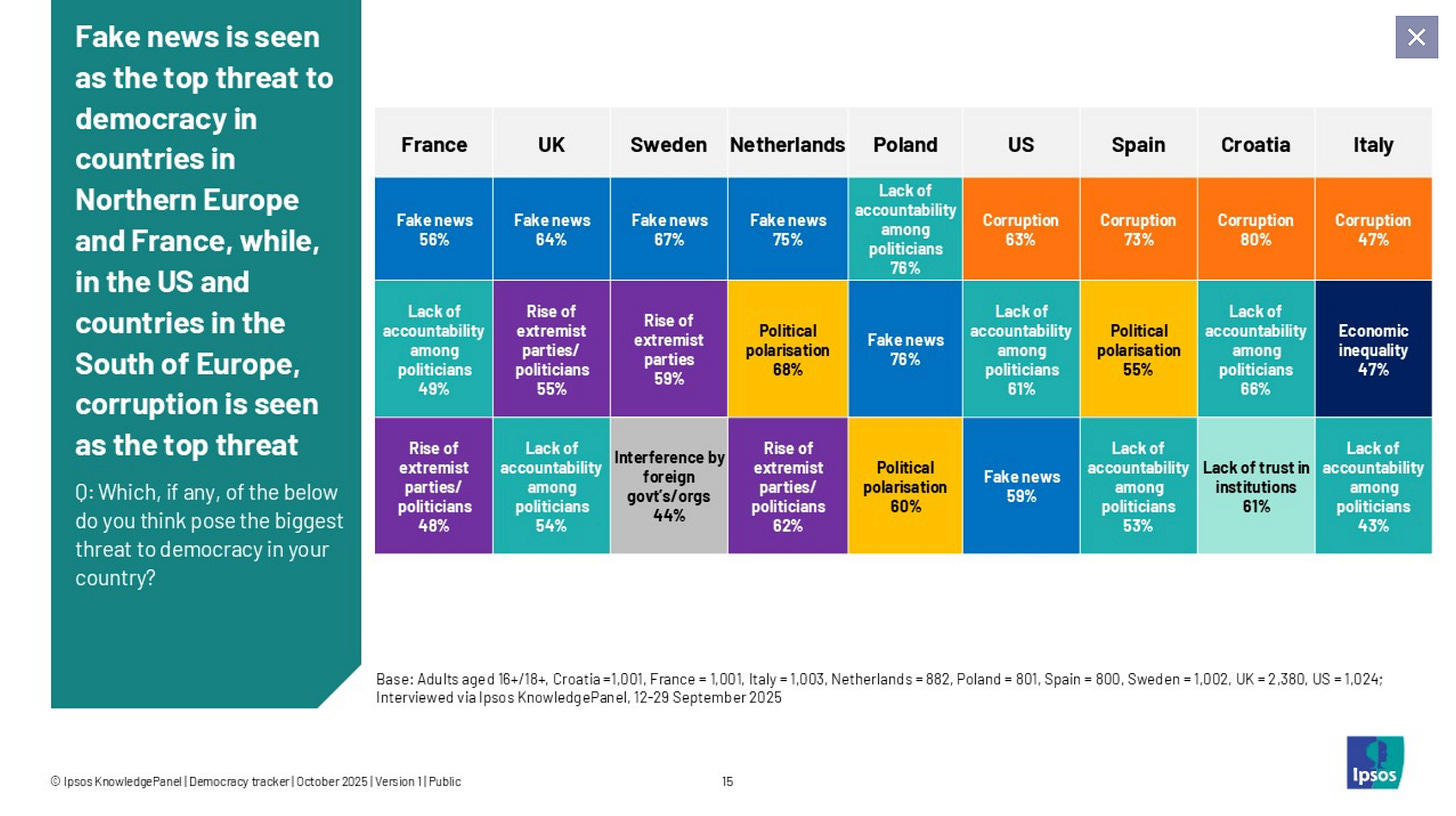

Misinformation and the media environment

A huge share of respondents list disinformation and media polarization as threats to democratic stability. When no common information baseline exists, public debate feels impossible.

Fears about the future

Many believe democracy has deteriorated over the past five years, and expect it to worsen. Economic uncertainty, rapid technological change, culture-war politics, and global crises all feed into a sense of fragility.

Frustration with outcomes, not principles

This is crucial: people aren’t turning away from democracy because they no longer believe in it. They’re unhappy because they believe democracy should work better than it currently does.

This distinction matters. Dissatisfaction isn’t the end of democracy — it’s a signal that citizens expect more, not less, from their governing systems.

The Hopeful Part: People Still Want Democracy

Despite the bleakness of the satisfaction numbers, the Ipsos survey reveals something incredibly important:

Strong majorities still support democracy as the best form of government.

Most people in these countries do not support authoritarian alternatives. They do not want to give up elections, civil liberties, or open debate. What they want is a version of democracy that lives up to its promises — one that produces fair outcomes, holds leaders accountable, and protects rights effectively.

This is why the dissatisfaction is “okay.” Not because everything is fine — far from it — but because dissatisfaction can be constructively channeled. It means the public is paying attention. It means expectations are high. And high expectations are a democratic asset, not a democratic weakness.

Democracy is supposed to frustrate people sometimes. It’s slow, deliberative, messy. But it’s also flexible. It can evolve, expand, and improve. And historically, democracy has strengthened precisely when citizens demanded more from it.

So What’s the Path Forward? Rebuilding, Not Romanticizing

Western democracies aren’t doomed. They’re strained — strained by polarization, by inequality, by a media ecosystem that rewards outrage over understanding, and by institutions that haven’t kept pace with modern expectations.

If anything, the survey suggests a clear path forward:

Strengthen trust through accountability

Democracies rise when leaders are held to clear, consistent standards. Anti-corruption measures, fiscal transparency, and independent oversight matter more now than ever.

Reinforce shared information spaces

Without a baseline of facts, democratic disagreement becomes democratic dysfunction. Investments in media literacy, responsible tech regulation, and public-interest journalism can help rebuild this foundation.

Modernize institutions to meet modern expectations

Citizens want faster responsiveness, more transparency, and less bureaucratic distance. Digital governance, participatory budgeting, and simplified public services can reduce the gap between people and policymakers.

Address economic fairness

Economic dissatisfaction is political dissatisfaction. When people feel locked out of opportunity or burdened by stagnant wages and rising costs, faith in institutions declines. Economic policy and democratic renewal are linked.

Encourage civic participation beyond election day

The future of democracy isn’t just about voting. It’s about ongoing engagement — community organizations, unions, volunteer networks, issue advocacy, and public consultations. Democracy must be lived between elections, not just measured by them.

The Bottom Line: People Haven’t Lost Faith — They’ve Raised the Bar

If democracy were truly failing in the eyes of Western citizens, we’d see mass abandonment of democratic principles. We don’t. What we see instead is a demand for improvement. Dissatisfaction is pushing people to think critically, ask harder questions, and hold leaders accountable.

And that’s okay. Healthy democracies grow from tension, not complacency.

The Ipsos findings don’t tell a story of collapse — they tell a story of recalibration. Democracy isn’t dying; it’s being tested. And the good news is that people still believe it’s worth fighting for, fixing, and building upon.

A democracy that can evolve is a democracy that can survive.

Written by Antowan Batts

Reader Question: What are your views on the state of democracy and trust in institutions?

Antowan- Thank you for your contribution -- it's great. My response is to take a walk down memory lane, and talk a little about Aristotle's Politics, and my take on some implications. In the Politics, Aristotle talks about three types of government, and their "good" and "bad" forms. The three types are Monarchy -- rule by one; Aristocracy -- rule by a few; and "Polity" -- rule by many. If you consider only the "good" forms, Monarchy is the best of the three -- rule by an intelligent monarch whose focus is the good of the polity, including the well-being of its population. Polity is the worst of the "good" forms, as it is based on the votes of a large number of people with varied intelligence and understanding and sometimes competing interests. If you flip the scenario and look only at "bad" forms, clearly the worst is the malevolent and selfish Tyrant who wants only his own benefit. Oligopoly is less bad, as the malevolent and selfish rich are fighting each other, which gives some scope for others to benefit. Democracy is the most chaotic of the forms of what is in practice a "scramble for resources", such that a number of groups get much of the pie.

It seems to me that this looks a lot like a competition grid that we show in our economics courses, and that Democracy wins what is effectively a "Nash equilibrium" -- as Churchill said: "democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time." It is always messy, but particularly so when it is a fight to see who can suck the most from the teat of government. When government is captured by people who see it as a cow to be milked, we can expect bad results. The modest Social Democracy that already exists in the USA especially benefits old people, who cling to their benefits with ferocity, but the rest is an unseemly battle to see who gets the most -- the military-industrial complex, the poor, investors, industrialists, the health care sector (keep in mind that by far the largest lobbyist spending in the US is by the health care industry, and by golly! we have by far the most expensive health care in the world). Unless and until a way can be found to allocate goods and services and manage regulation in the service of the real needs of the US population, we will be stuck with what we might call "the Soviet Problem" -- the corruption of gatekeepers to resources by the wealthy and powerful via the political system. Plato in his Republic supposed this was a problem of raising the population in a system based on making sure each citizen is in the correct place in their society. For us it is ultimately a problem of Public Choice Theory --- let us all drink to that most ornery of economists: James M. Buchanan, Jr!

Good food for thought, " a sweeping look across Western nations that reveals something both troubling and oddly hopeful"