America’s Affordability Crisis

Why it is a tough battle to fight

The White House is under growing pressure over affordability, and it shows. Americans feel broke, complaints are getting louder, and concern about the cost of living is now cutting across party lines. In response, the administration has leaned heavily on messaging. Specifically, they cite selected economic indicators while urging voters to be patient. Next month, next year, or sometime in the future, conditions will improve.

That tension was on full display in the recent primetime address. The message was twofold: the economy is currently strong, but households continue to suffer from problems inherited from the past. While both claims may contain elements of truth, they are contradictory. For many Americans, the issue is not who to blame; it’s why everyday life still feels so expensive.

This disconnect is not just political. It reflects a deeper economic reality about what affordability is and why it is so difficult to fix.

The Economics

Affordability is not the same thing as inflation. Inflation tells us how fast overall prices are rising. Affordability tells us whether people feel their income can cover the costs of daily life, housing, childcare, food, transportation, and insurance, to name a few. Those experiences vary dramatically across households, regions, and income levels.

That makes affordability difficult to measure and even more challenging to address through policy. There is no single affordability index, only a collection of pressures that show up differently depending on where you live and what you earn, and what you need to spend your money on. When leaders point to strong averages, many households feel ignored. When they promise future relief, people hear delay.

In practice, there are only a few ways affordability improves:

1. Overall prices fall.

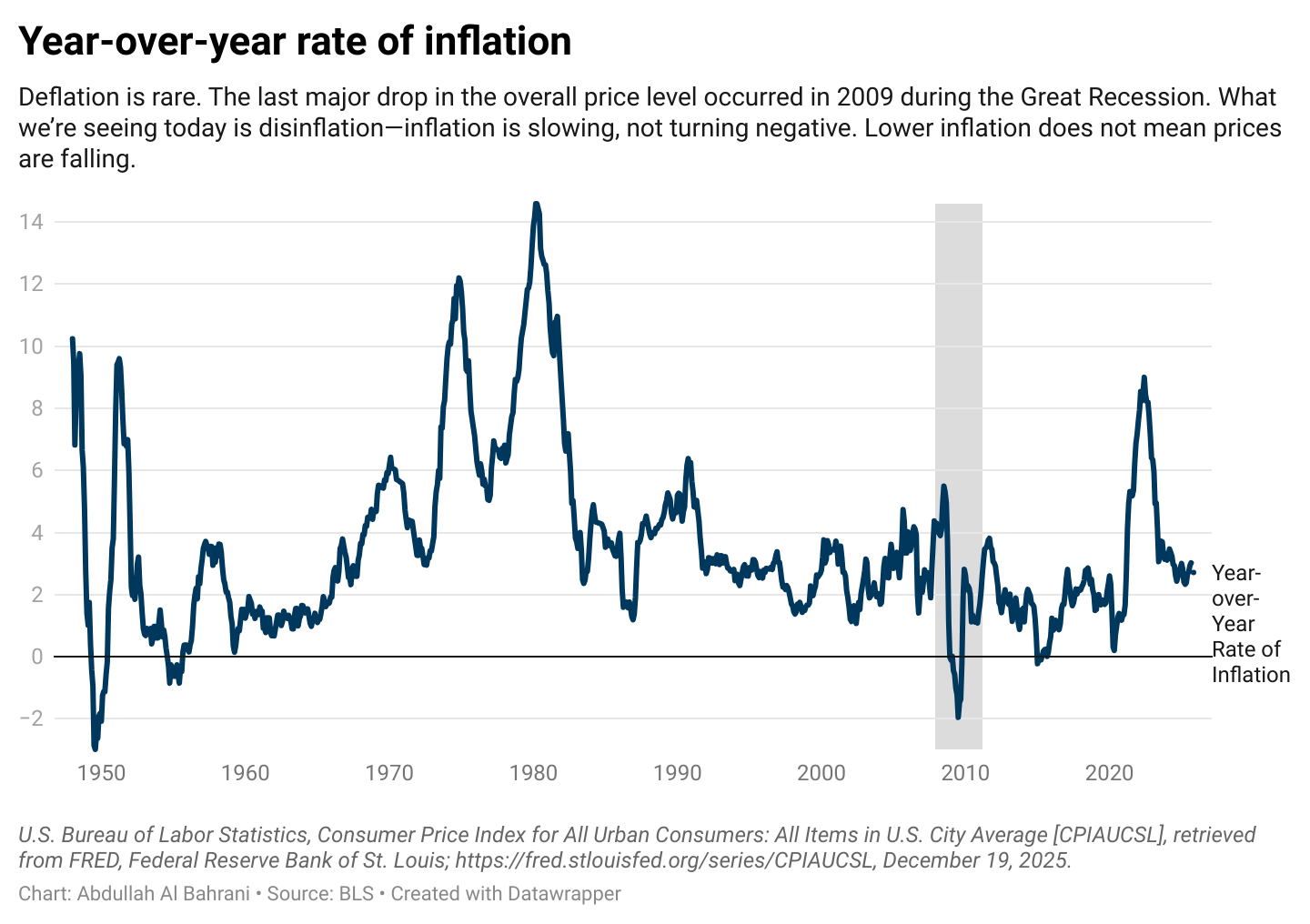

Broad declines in the price level usually occur during deep recessions. The last major episode was the Great Recession. Layoffs, bankruptcies, and financial stress often accompany falling prices. These are outcomes that few people actually want. The pain is real and doesn’t solve the affordability problem; it merely reduces prices. Our goal should not be to have lower prices.

2. Real wages rise meaningfully.

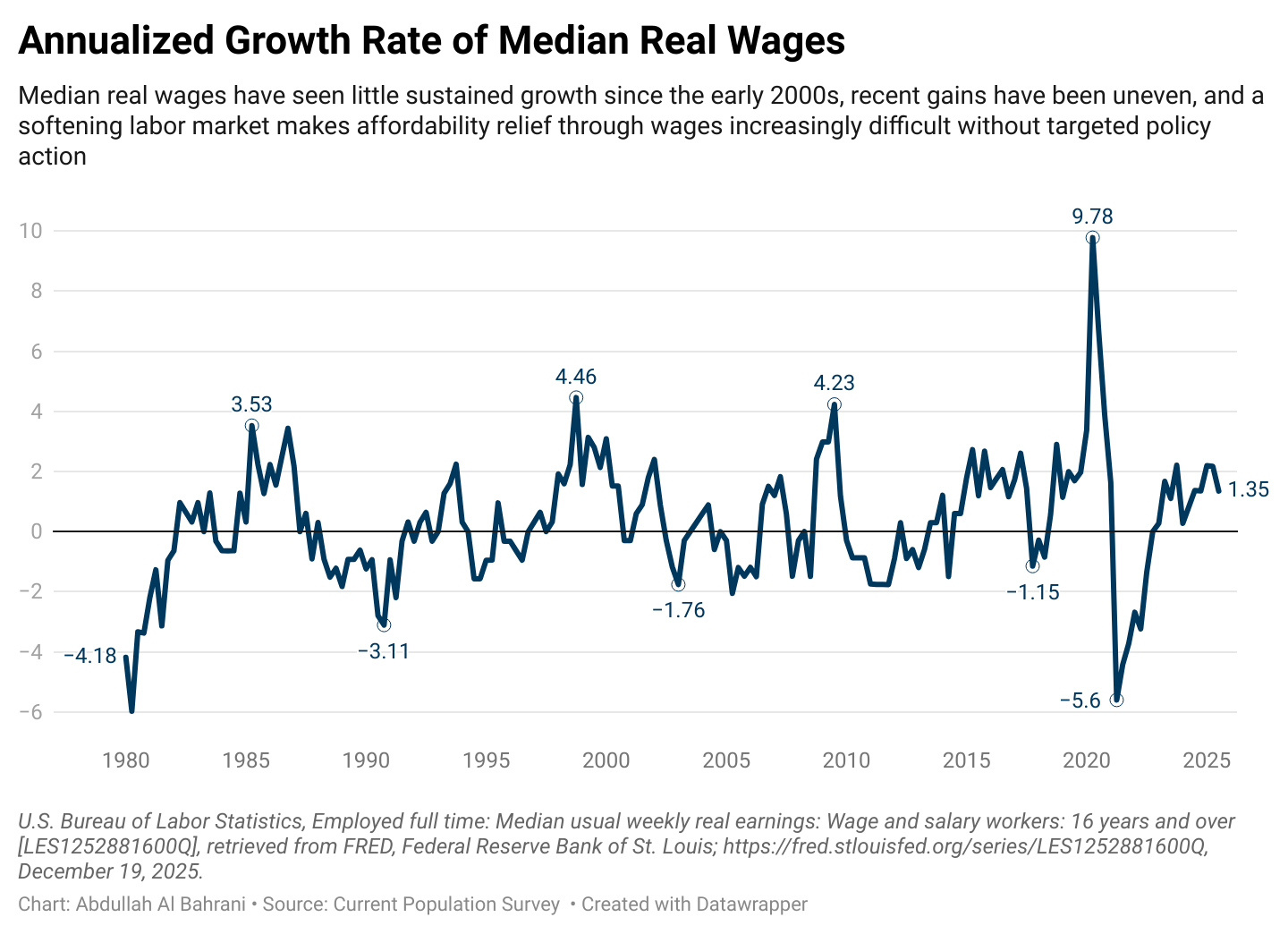

For most workers, real wage growth rates have hovered near zero since the early 2000s. Recent gains have been uneven, and a softening labor market makes sustained wage growth harder to achieve. Wage increases can provide relief for affordability, but raising wages across the income distribution requires targeted and well-designed policies. Those have not been presented yet.

3. Money becomes cheaper and more abundant.

Lower interest rates and easier credit can make life feel more affordable by boosting access to borrowing and inflating asset prices. But this approach carries a well-known cost: inflation. We saw this clearly after 2020. Cheap money feels good at first, then lingers long after.

None of these options is clean. Each involves tradeoffs that are politically uncomfortable to acknowledge.

A Note on Inflation Data

Yesterday’s CPI report came in lower than expected at 2.7%, which some will celebrate as progress. Caution is warranted. Because the October CPI was canceled, the Bureau of Labor Statistics relied on alternative data sources to complete the index. The number provides information, but not certainty.

More importantly, slower inflation does not automatically mean improved affordability. Prices may be rising more slowly, but they remain high, and many household budgets are still under strain.

A common mistake in public discourse is mistaking disinflation, the reduction in the inflation rate, for deflation, negative inflation. Disinflation means prices are rising, but at a slowing rate. Deflation means prices are falling.

The Bottom Line

Affordability is a real economic problem, not a messaging strategy. It cannot be fixed quickly, cleanly, or without tradeoffs. Slower inflation helps, but it does not erase years of price increases or guarantee relief for households already stretched thin.

Until policymakers narrow the problem and speak honestly about the economic tradeoffs involved, Americans will continue to feel a gap between headline data, political promises, and their lived experience. The economy can appear healthy for some, while affordability remains painfully out of reach for many.

Inflation may be easing. Affordability is a much harder fight.

Question to the readers: Have you enjoyed listening to the narrated newsletters?

Great work!