Can Virtual Reality Teach Economics Better Than a Textbook?

Educators who Innovate, Inspire.

The Problem

If you’ve ever taught or taken a course on economic development, you know the challenge: the numbers are staggering, but they rarely feel real. A $150-a-day consumption level in the U.S. versus $10 or even $2 in many emerging markets is a meaningful statistic, yet people still struggle to grasp what that difference looks like on the ground.

Enter Andrew Jonelis, a University of Kentucky economics Ph.D graduate and now an assistant teaching professor at Syracuse University. Jonelis is trying something bold: using virtual reality to bring emerging markets straight into the classroom.

Instead of imagining how people navigate cities like Port Moresby or Dar es Salaam, students step directly into those environments. During class, you can find them standing in a fruit market, floating over informal settlements, or walking down streets lined with open-air vendors. Suddenly, the gap in living standards is no longer an abstract concept. It’s something you can see.

The Economics

Economics is, at its core, the study of choices in the face of scarcity. But those choices vary dramatically around the world. That’s why study abroad programs have historically been among the most powerful tools in economics education. They expose students to the real-world conditions behind the data.

As my longtime collaborator Darshak Patel often says, “Study abroad transforms classrooms into real-world laboratories where culture teaches and curiosity drives learning. It pushes students to move beyond observation—to engage, analyze, and connect in meaningful ways. The world is their canvas, and only they can choose how boldly they paint it.”

But here’s the challenge: not every student can travel. And not every program has the resources to send students across continents.

That’s where VR becomes more than a tech novelty; it becomes an access point.

Jonelis begins the semester as most of us do, grounding students in statistics on consumption, infrastructure, and poverty. But he knows something is missing.

“I’ve been to some of these countries,” he says, “and you can very clearly see what struggling with international poverty looks like. Just reading about it does not have the same effect.”

He’s right. Data can explain the what, but not always the feel.

So when a student “lands” in a densely populated neighborhood in Papua New Guinea, Jonelis points to the screen: “Right there—you’ve got informal housing next to developed neighborhoods. That’s economic development in action.”

Another student explores Tanzania and notes, “Seeing the areas of informal housing we discussed in class really helped me understand what we mean when we say ‘developing economies.’”

VR turns abstract concepts into spatial, human experiences: infrastructure gaps, informal markets, sanitation challenges, and transportation constraints. Students aren’t merely hearing about them, they’re looking at them.

Patel’s insight captures exactly why this matters: “The insights students gain abroad stay with them long after they return home, and in the process, they develop knowledge, empathy, and confidence that no traditional lecture can replicate.”

VR isn’t a replacement for study abroad, but it can replicate aspects of its learning power for students who might otherwise never see these environments.

The Power of Storytelling

These moments matter because development economics is visual, spatial, and human. You learn as much from observing roads, wiring, drainage, and market stalls as you do from reading growth theory. VR lets students contextualize statistics: how people get to work, how water is accessed, how electricity is delivered, how public services extend, or fail to extend, across communities.

Darshak Patel, my longtime friend and collaborator, has written extensively about how exposure to international environments deepens students’ understanding of global economics. Studying abroad accomplishes that. Now, VR can offer parts of that experience to students who might otherwise never see these environments. While it might not replicate it fully, Andrew Jonelis's innovation allows us to bring some of this experience to our students.

“Numbers and charts don’t hit home the same way,” Jonelis says. And he’s right. His assignment brings economics to life by leveraging immersive technologies.

A Note on the Technology

The immersive experience in Jonelis’ class is powered by WorldLens (formerly EarthQuest), a VR platform that lets users explore cities and communities around the world. Students use WorldLens through Syracuse University’s Digital Scholarship Space, which supports faculty experimenting with new forms of experiential learning. The assignment itself is Andrew’s intellectual property—and I want to respect that—but the technology behind it shows what’s possible.

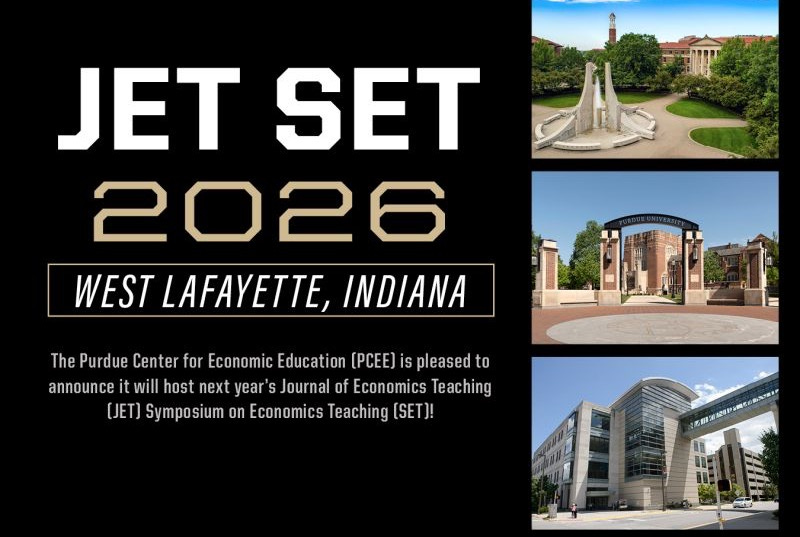

I would love to see this lesson plan in a Scholarship of Teaching Journal, such as Journal of Economics Teaching. It would also make an excellent presentation at JET SET at Purdue July 29-31, 2026. Submissions for July’s conference are open.

The Bottom Line

VR won’t replace study abroad, but it democratizes the kind of experiential learning that transforms how students understand global inequality. It allows students to “travel” across five continents in a single class session, building intuition about markets and scarcity in a way that reading alone can’t.

Most importantly, it keeps economics rooted in real human lives. When a student removes the headset and says, they have developed a stronger connection with the human story behind the data.

As we always say at Decode Econ, economics isn’t only about equations. It’s about the lived realities those equations try to describe.

And thanks to innovations like this, those realities are becoming easier to see.

This is great! I used a similar pedagogy at Penn State in my Labor Econ class and my Econ of Crime course. The students got to see a really neat side of the world without leaving campus.