Climate Change: a Million Paper Cuts

Is Climate Change Real?

We’ve been arguing about climate change for decades. Not whether it’s real anymore, most of us are past that, but what to do about it. Scientists spent years waving red flags: melting ice caps, bleached coral reefs, dying forests, you name it. They sounded the alarm, and yet policy moved slowly.

Why?

Because even if we know something is bad, we tend to ignore it until we feel it, and we know exactly what it will cost us to change.

And now we do.

The What

A new working paper by economist Solomon Hsiang, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, provides policymakers and citizens with something they have been missing: a precise, empirically grounded estimate of how climate change will disrupt the global economy.

The takeaway? Climate change won’t affect us all equally.

Hsiang’s research reveals an unequal distribution of economic pain. Some regions, the hottest, poorest, and most vulnerable, will bear the brunt of rising temperatures and shifting weather. But nobody escapes. Even wealthy countries, which are better equipped to adapt, still face declining productivity, higher social costs, and ripple effects from global instability.

This isn’t about “saving the planet” in some abstract way. It’s about deciding what kind of world we’re willing to pay for, and who we’re okay with leaving behind.

Why It Matters

Economists love talking about externalities, but what are they? Negative externalities are costs that we do not pay directly but incur nonetheless. Often, these costs are due to someone else’s actions. Pollution is an example of a negative externality. So is untreated wastewater or secondhand smoke. Climate change is a negative externality, but it presents itself in a slightly different way.

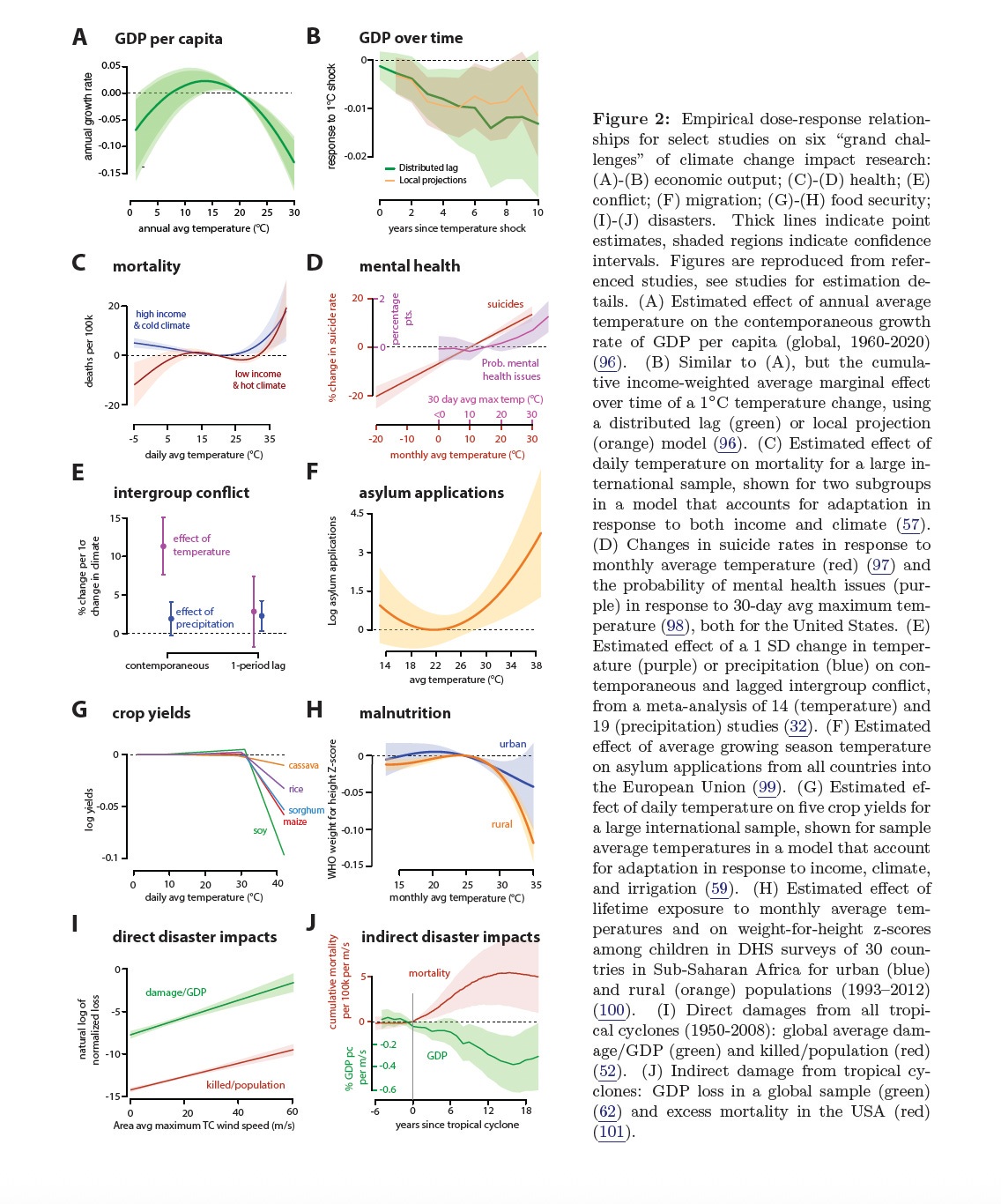

The most economically damaging effects of climate change aren’t the dramatic hurricanes or wildfires that make headlines. They’re the slow, everyday shifts—what Hsiang calls “chronic climate pressure.” This is what makes climate change so difficult to address: the costs are small at first, but they quietly accumulate over time until they become impossible to ignore.

These “minor” changes are:

Hotter average days lower worker productivity

Increased mortality during heat waves

Lower crop yields and higher food insecurity

More conflicts as resources become strained.

Slower long-term GDP growth, especially in hotter countries

Death by a thousand decimal points of growth. And we’re already feeling it.

A Closer Look: The GDP Effect

Hsiang’s team analyzed decades of empirical research to estimate the impact of rising temperatures on economic growth. The results aren’t pretty: hotter countries experience reduced productivity across labor, agriculture, manufacturing, and many other sectors. The damage doesn’t bounce back, either. Instead, it compounds, year after year.

By 2100, with 3°C of warming, the average person is expected to lose 20% of their income compared to a world without climate-driven losses.

To put it another way: climate change isn’t just an environmental crisis. It has a permanent impact on the income of billions of people.

And again, the pain isn’t evenly shared. Countries in the tropics—where temperatures are already high—face GDP declines of 30% or more. That’s not just slower growth. That’s a reversal of decades of development progress.

Health: The Hidden Cost Driver

Economics isn’t only about money; it’s also about what money measures. As Hsiang notes, health is one of the most valuable economic resources we have, and climate change is already degrading it.

Heat-related deaths are climbing.

Air pollution linked to wildfires is contributing to an increase in heart and respiratory illnesses.

Stress from extreme weather is worsening mental health outcomes.

Even our sleep is under threat. Rising nighttime temperatures reduce rest, which lowers productivity and impacts health.

By mid-century, the global mortality burden from heat alone could cost the world around 3% of GDP annually. That’s about $3 trillion per year in today’s money, due to people dying earlier than they should.

The Unequal Burden

A recurring theme in Hsiang’s work is the issue of inequality. Not only are poorer countries more vulnerable, but they also have the least capacity to adapt. Air conditioning, flood barriers, and reinforced hospitals all require significant capital investment. So even if the world warms by the same amount everywhere, the economic consequences are multiplied in places already struggling.

In effect, climate change is regressive. It taxes people with low incomes at a higher rate.

And yet, continued emissions today mainly come from wealthier countries and economies.

That raises a moral question for policymakers: How will nations justify doing less when doing nothing hurts those who’ve already been left out of the global growth story?

The Fork in the Road

When we hear about climate change costing us trillions, it often feels abstract and distant. However, what Hsiang’s paper reveals is that the costs of climate change are unfolding in real time, manifesting in rising food prices, declining productivity, and lower wages.

The longer we wait to act, the more expensive it gets.

This is why pricing carbon, taxing emissions, investing in green transitions, and building resilient public infrastructure aren’t just idealistic policy planks; they’re economic necessities.

The Bottom Line

So what should we do with this research?

For one thing, throw out the idea that climate change is something we can put off for a later generation. The last generation is here. The bill is here. And while we’ve already lost some ground, the models show that decisive action now can still save lives, foster growth, and preserve livelihoods.

Hsiang’s work puts climate change in dollar terms. Our politics needs to catch up.

Because pretending climate change is someone else’s problem isn’t just shortsighted—it’s bad economics. It ignores the true cost and problem.

Great article! The pain is real, every semester my students start businesses to help out a dent into climate change.

Great article! I'm impressed by your ability to put these out almost every day.

I think an interesting aspect to add to this is insurance companies looking forward and adjusting premiums to account for climate change.