Declining Labor Mobility in the U.S.A

A currency union that depends on movement

The United States is one of the world’s most successful currency unions. We share a single currency, a single central bank, and a single interest rate across 50 very different state economies. That arrangement has powered growth for more than a century.

But currency unions come with a tradeoff.

When one region is booming, and another is struggling, the Federal Reserve cannot tailor interest rates to local conditions. The same rate applies everywhere. That’s where labor mobility matters. In theory, workers move from weak regions to strong ones, thereby absorbing shocks that monetary policy cannot absorb.

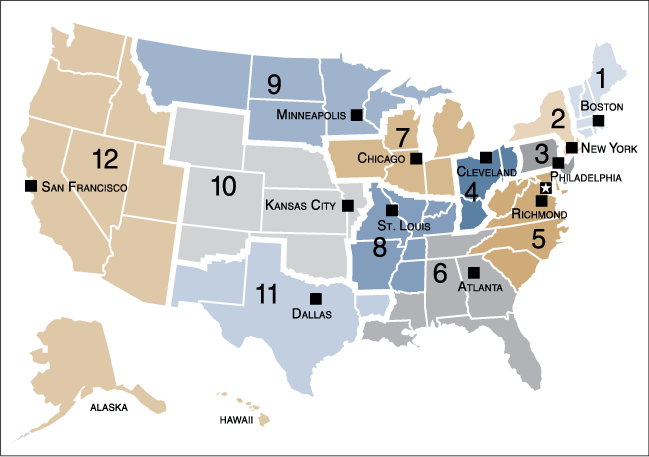

This is also why the Federal Reserve's structure matters.

While monetary policy is set centrally by the Board of Governors and the FOMC, the Federal Reserve System is deliberately decentralized. The twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks collect on-the-ground information from businesses, workers, and local governments in their districts. Through surveys, regional data, and direct outreach, they communicate local economic conditions, such as labor shortages, layoffs, housing pressures, and credit constraints, to policymakers in Washington.

In other words, the Fed relies on regional banks to listen to the economy, even if it can’t fine-tune interest rates for each place.

But listening is not the same as fixing. When labor mobility weakens, even the best regional intelligence cannot fully offset regional mismatches. Monetary policy becomes blunter, adjustment slows, and local downturns risk becoming permanent.

That’s where we get to today’s problem: Americans are moving less than they used to, and that has an impact on the economy.

The Economics: why labor mobility is the shock absorber.

In a system with flexible exchange rates, struggling regions can regain competitiveness through currency depreciation. In a currency union, that tool is gone. This also applies to currencies that are pegged to the dollar, like in Oman.

According to the theory of optimal currency areas (OCA), economist Robert Mundell has argued that for a currency union to function smoothly, at least one of these must adjust: wages, fiscal transfers, or labor mobility

In the U.S., labor mobility has historically done much of the heavy lifting. Workers moved toward jobs. Regions adjusted. Unemployment stayed lower than it otherwise would have.

However, recently, that mechanism has been weakening.

New research on labor mobility.

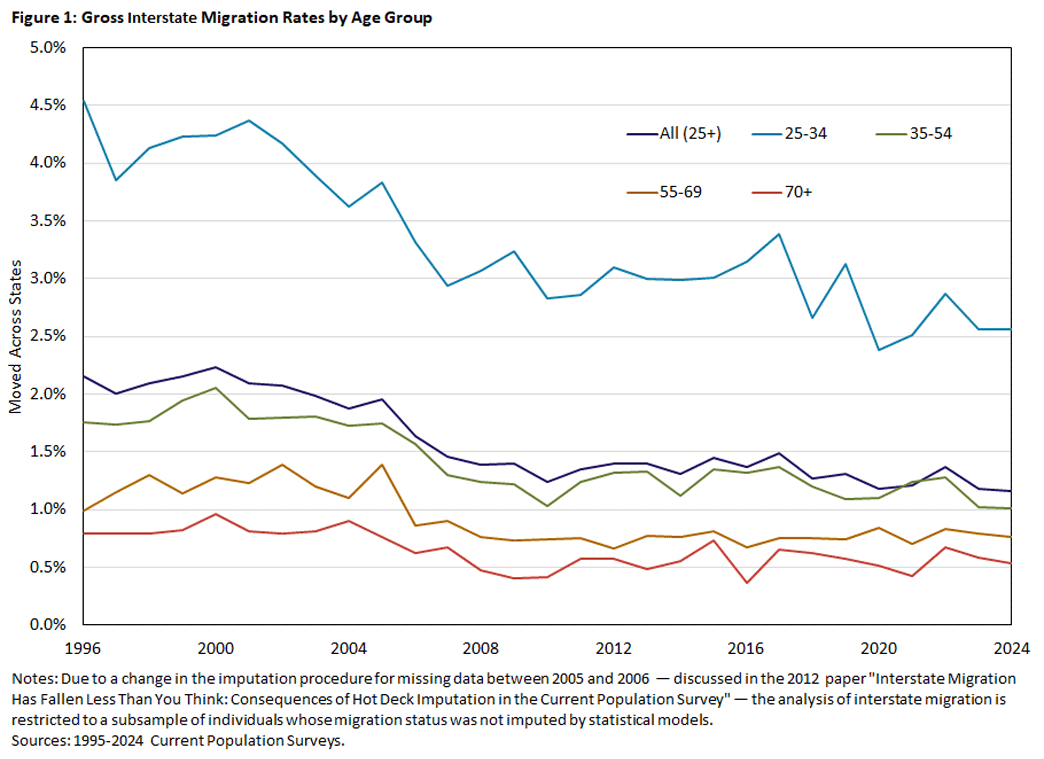

Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond indicates a steady decline in interstate migration across all age groups since the mid-1990s. Younger workers still move more than older workers, but even their mobility has fallen sharply.

The authors provide several reasons why this might be the case

Population aging

Dual-earner households (making relocation harder)

Rising housing costs in high-opportunity cities

Geographic sorting by education, driven by agglomeration economies

Narrower wage differences across regions for similar jobs

The key point: fewer people are willing or able to move, even when regional economic conditions diverge.

What the data say about earnings and moving.

A common explanation is that “moving just doesn’t pay anymore.” The data don’t support that story.

A detailed study using Social Security administrative records (Patrick Purcell, 2020) finds:

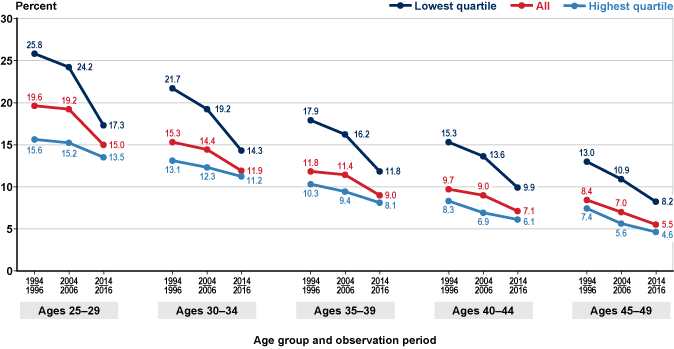

Geographic mobility fell substantially from 1994 to 2016

Employer switching remained common

Younger movers often earned more several years after moving

Earnings gains from moving did not disappear over time

In short, Americans didn’t stop moving because the returns vanished. They stopped moving for other structural reasons.

This distinction matters. If mobility fell because returns collapsed, the economy would simply be adapting. But if mobility declines while returns remain, adjustment failures begin to manifest elsewhere, such as in structural unemployment.

Structural unemployment and the trade shock we misjudged.

This issue was clearly highlighted in a recent episode of Planet Money, where David Autor reflected on what economists got wrong about trade with China.

One key assumption:

Workers displaced by trade would move across regions and across industries.

Many didn’t. Instead, job losses became geographically concentrated. Labor markets didn’t clear. Communities stagnated. Structural unemployment rose, not because jobs didn’t exist, but because workers weren’t matching up with where jobs were, and their skills began to deteriorate.

Declining labor mobility turns regional shocks into persistent economic scars. Trade wasn’t the problem; labor mobility was not as frictionless as we anticipated. The government could have facilitated this transition through educational and relocation programs, but it was slow to do so. Americans stayed local and watched their opportunities disappear; they blamed trade when it was actually declining labor mobility.

The bottom line.

Labor mobility isn’t just about personal choice. It’s a core macroeconomic stabilizer in a currency union, and the U.S. is a large currency union.

When workers stop moving:

Regional downturns last longer

Cyclical unemployment lingers and turns into structural unemployment

Inequality across places deepens

Monetary policy becomes less effective

As I teach structural unemployment this semester, this is a real-world example. The U.S. economy assumed that mobility would adjust. Increasingly, it doesn’t.

That leaves us with a harder question: If workers won’t move, what policies will help the economy adjust instead?

Labor mobility is such an important topic that even strategy games incorporate it now. We also saw it in historical contexts like serfdom and other policies like it. Limited mobility can stagnant not just a local economy but the macro one as well if it widespread enough. Great post as always.

I would love to see the trend pre-Internet.

Aside from that, I think the two likeliest candidates are some of which you mentioned: 1. Dual income households and 2. Geographic sorting by education.

On the second one, it looks like the lowest quartile earners saw the strongest dip. It makes sense given that jobs that don't require an education are pretty versatile and generally needed in urban and rural communities. That geographic ubiquity doesn't really apply as much to people with degrees. That might be why the gap in moving percentage isn't as large now. I imagine the gap still exists due to the stability of higher earning jobs.