Did Congestion Pricing Work in NYC?

One year later, what does the data say?

One year ago, New York City implemented a congestion-pricing scheme.

Drivers entering Manhattan’s busiest core were required to pay a fee, and the reaction was immediate and loud. Critics warned that congestion pricing would harm businesses, keep workers at home, push traffic into surrounding neighborhoods, and barely reduce pollution.

We are now twelve months into this experiment. What does the data tell us? Let us look into what has happened since.

The Problem: A Policy Everyone Said Would Fail

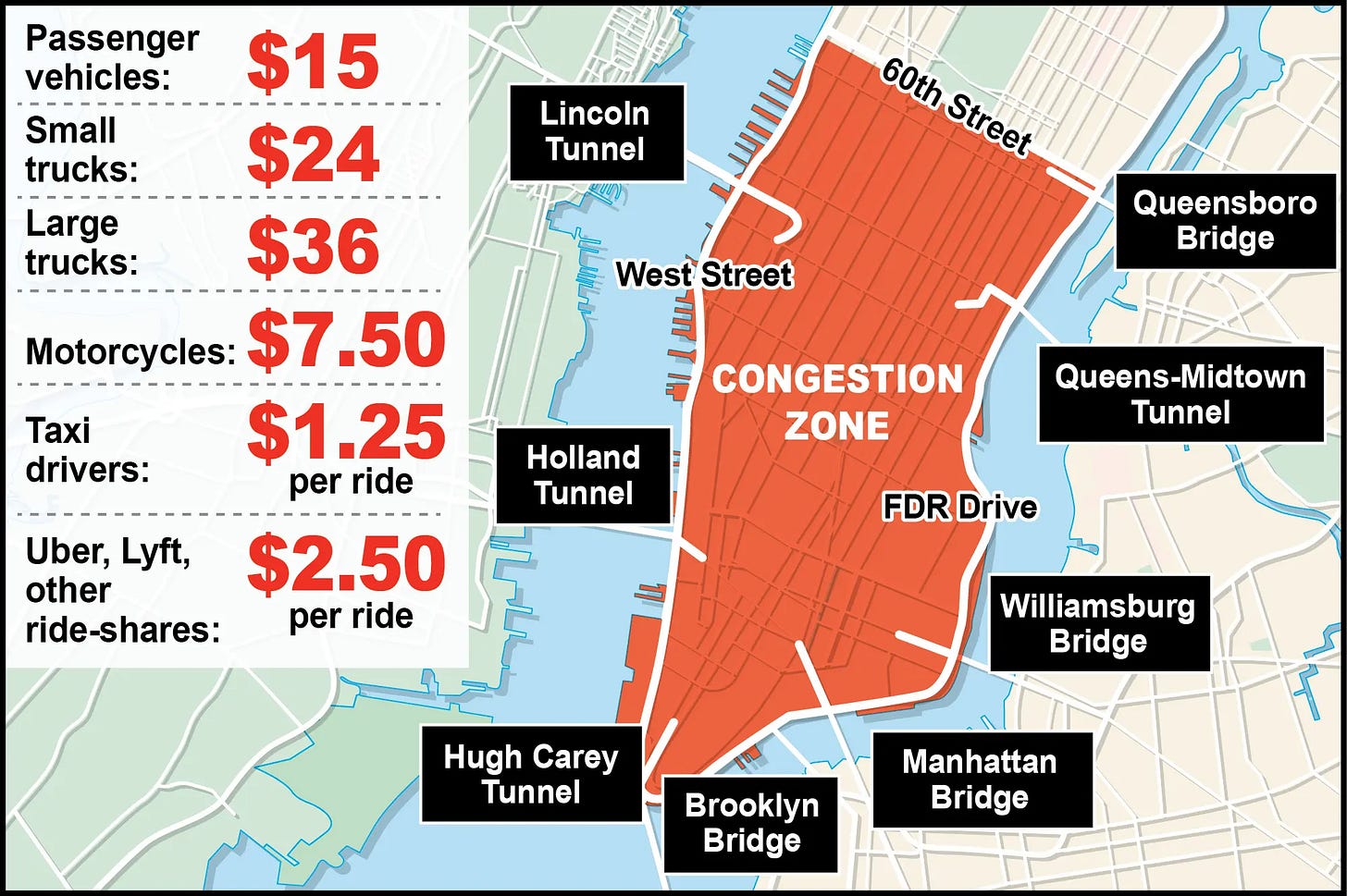

This map, provided by the NY Post, shows the pricing structure for vehicles entering Manhattan.

Critics of the policy warned that it would affect small businesses, Broadway show attendance, and the return-to-office trend, and would not reduce traffic because people would not switch to public transportation.

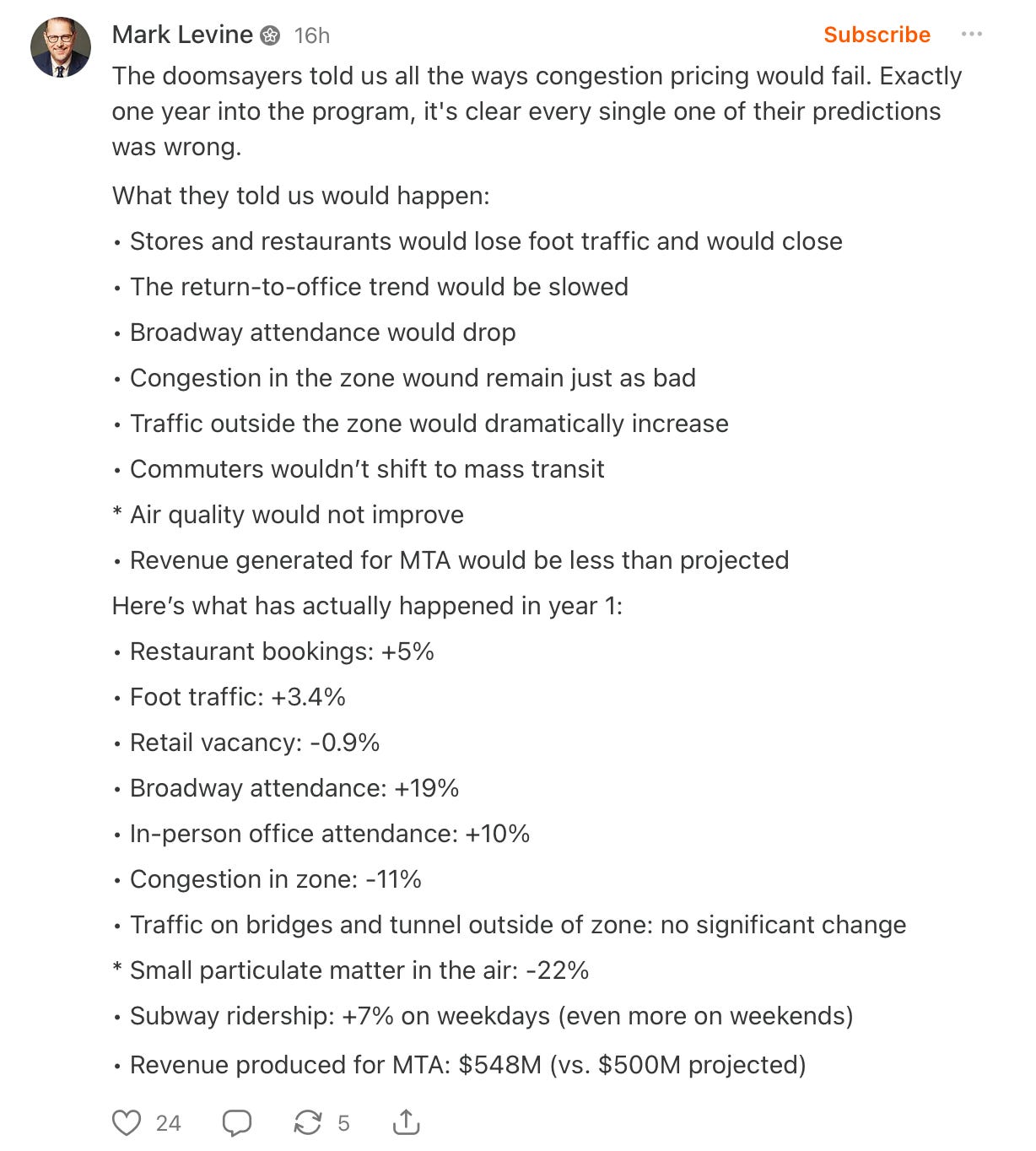

Mark Levine , New York City’s Comptroller, summarized his observation over the past year on his Substack note.

According to his post, here are the year-one outcomes:

Restaurant bookings: +5%

Foot traffic: +3.4%

Retail vacancy: –0.9%

Broadway attendance: +19%

In-person office attendance: +10%

Congestion inside the zone: –11%

Traffic outside the zone: no significant change

Subway ridership: +7% on weekdays

Revenue for public transit: $548 million (vs. $500M projected)

These are trends and do not constitute a scientific analysis of the impact of the pricing scheme. To that end, we would have to rely on the academic research discussed below. First, I discuss the economic rationale for implementing congestion pricing.

The Economics

From an economics perspective, congestion pricing isn’t a radical idea. It is a common solution economists recommend.

Driving in a dense city creates costs that drivers don’t fully pay for: slower traffic for others, more pollution, more noise, and higher accident risk. Economists call these negative externalities.

That’s the core problem.

The cost to the individual driving is lower than the cost to society. A basic principle of microeconomics states that the efficient level of consumption is achieved when prices reflect all costs associated with consumption. When prices are below true costs, too much activity occurs. In this case, too many cars in Manhattan.

Congestion pricing functions like a Pigouvian tax. This tax is a fee imposed on third parties to offset the costs of an activity. Raising the private cost of driving leads to behavior changes. Some will not take that additional trip; they might shift to off-peak hours or switch to public transit.

The policy isn’t about banning cars; it’s about aligning incentives.

And the theory predicted exactly what we’re now seeing in the data.

The Evidence: What the Nature Study Shows

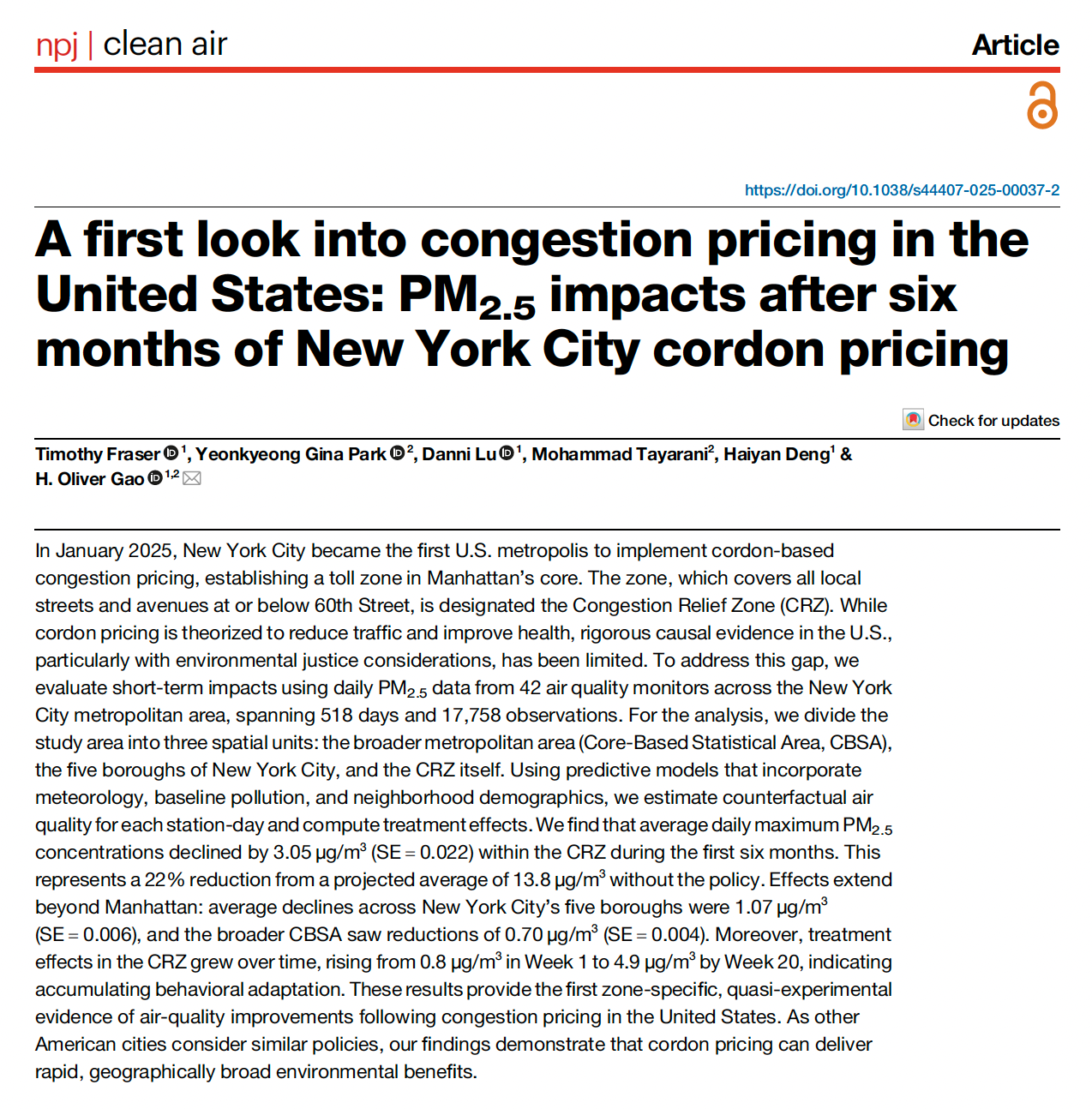

The strongest confirmation comes from a new peer-reviewed study published in Nature.

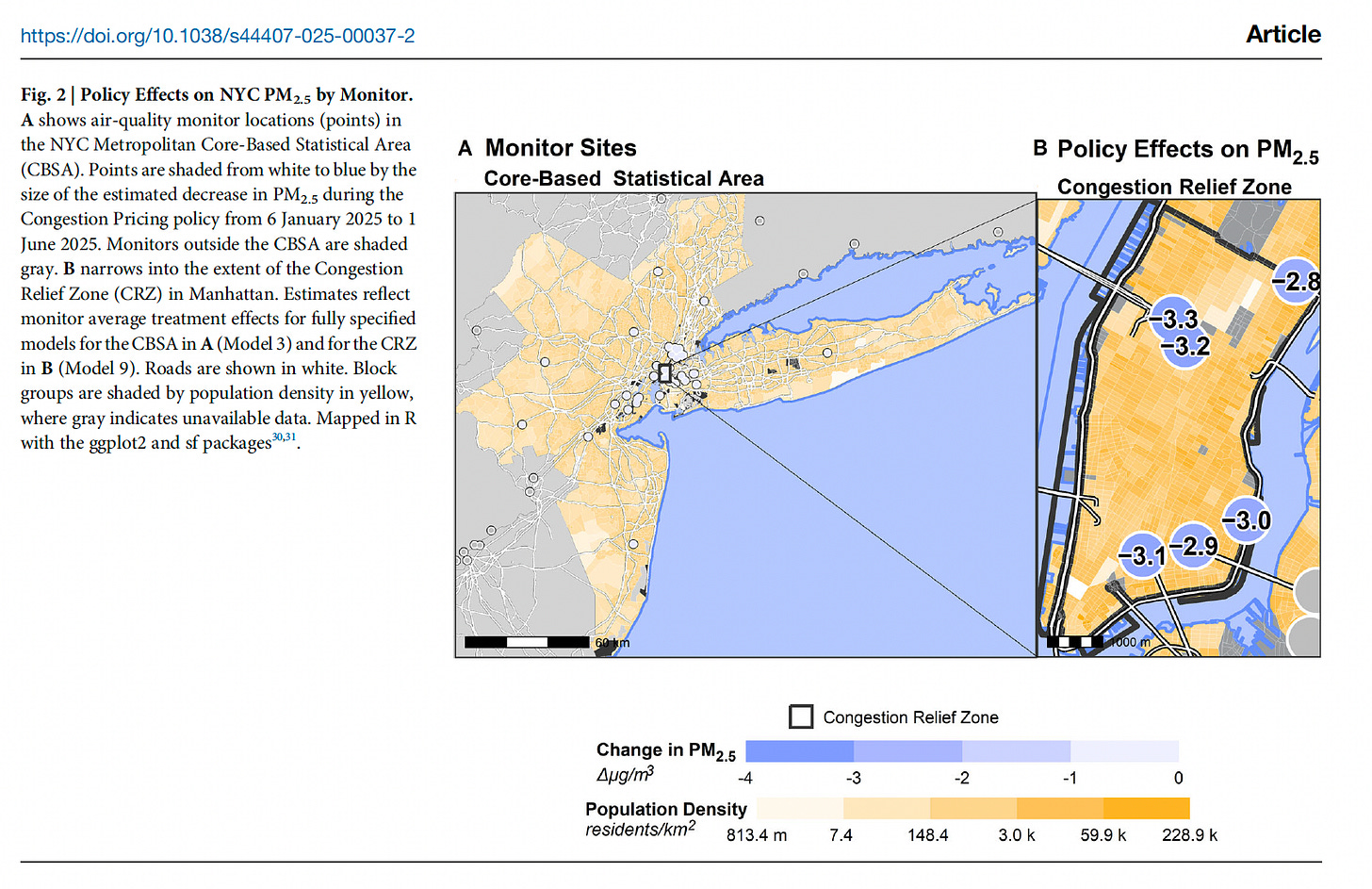

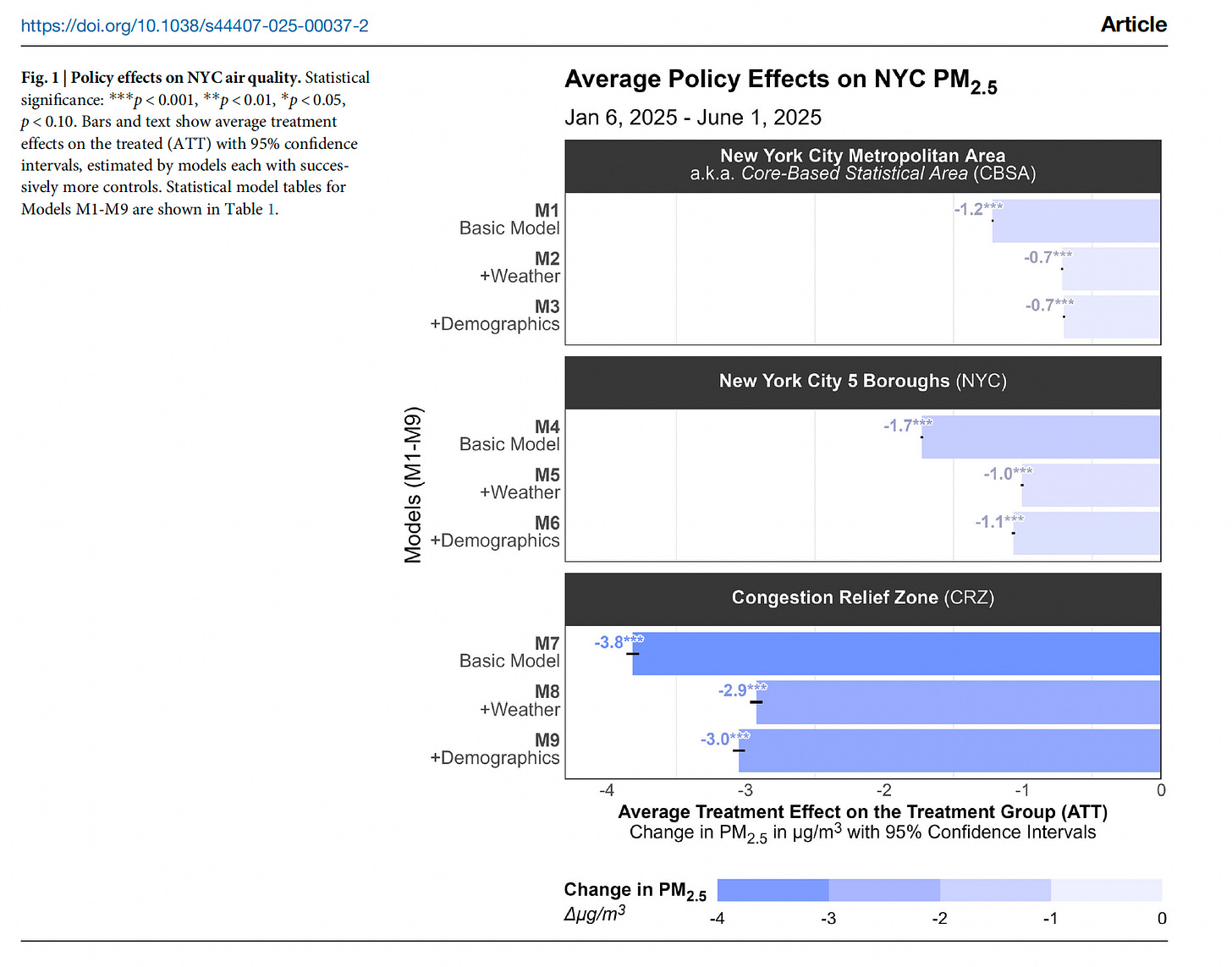

Instead of relying on projections and trends, researchers analyzed daily PM2.5 air pollution data from 42 monitoring stations across Manhattan’s Congestion Relief Zone, New York City’s five boroughs, and the broader metropolitan region.

They examined 518 days of data and used predictive models that controlled for weather, baseline pollution trends, and neighborhood characteristics. This enabled them to estimate the pollution levels that would have prevailedwithout congestion pricing.

The results were interesting:

Inside the congestion zone: PM2.5 pollution fell by 3.05 μg/m³, a 22% reduction relative to the counterfactual.

Across all five boroughs, Pollution declined by 1.07 μg/m³.

Across the broader metro area: Pollution fell by 0.70 μg/m³, showing benefits extended well beyond Manhattan.

More importantly, the effects increased over time.

Pollution reductions were modest in the first week but nearly six times larger by Week 20, indicating sustained behavioral change as commuters adapted.

The Bottom Line

Congestion pricing made the city cleaner and less congested with cars while generating hundreds of millions of dollars to support public transit. What is still to be examined is the impact of this policy on business activity. Although Mark Levine provides data on business activity, it is unclear whether those numbers would have been higher had the congestion-pricing model not been implemented.

In this case, the pricing scheme improved air quality. When markets failed, smart pricing helped fix them.