The Law That Changed Marriage and Divided America

In 1980, marriage looked much different than it does today. Back then, people across all education levels were more likely to marry, and divorce was high for everyone after the big surge of the 1970s. Today, the story has split into two. Adults with college degrees are just as likely to marry now as in 1980, but are less likely to divorce. But for those without a college degree, marriage has become less common and divorce more common. This has created a sharp “marriage divide” and “divorce divide,” where education (and income) now plays a central role in who marries and who stays married.

How Much Have Divorce Rates Changed by Education?

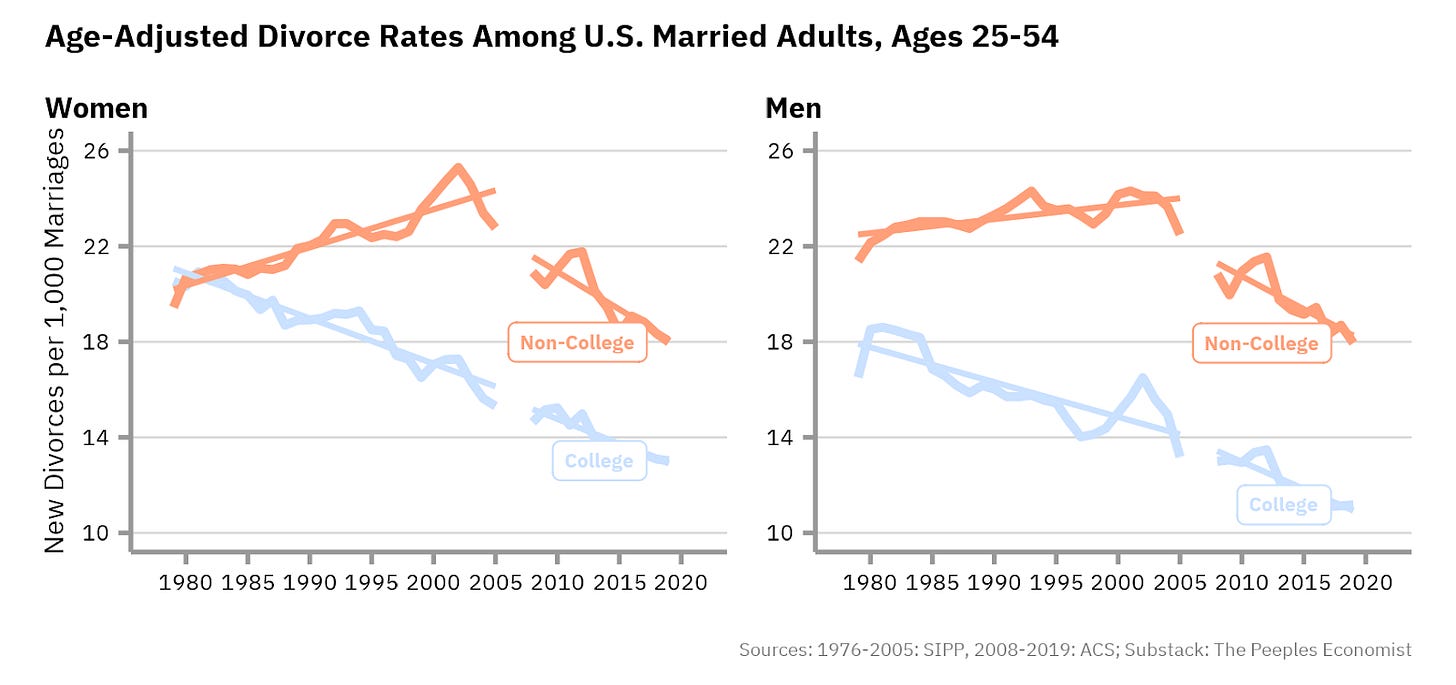

The divorce divide has grown more for women over time than for men. In the graph below, I document the annual divorce rates for men and women. This represents the number of marriages in the U.S. that end in divorce each year, per 1,000 marriages in each group. Of course, I am not the only one to document this fact, as it has been a topic of interest in economics and sociology research for years.

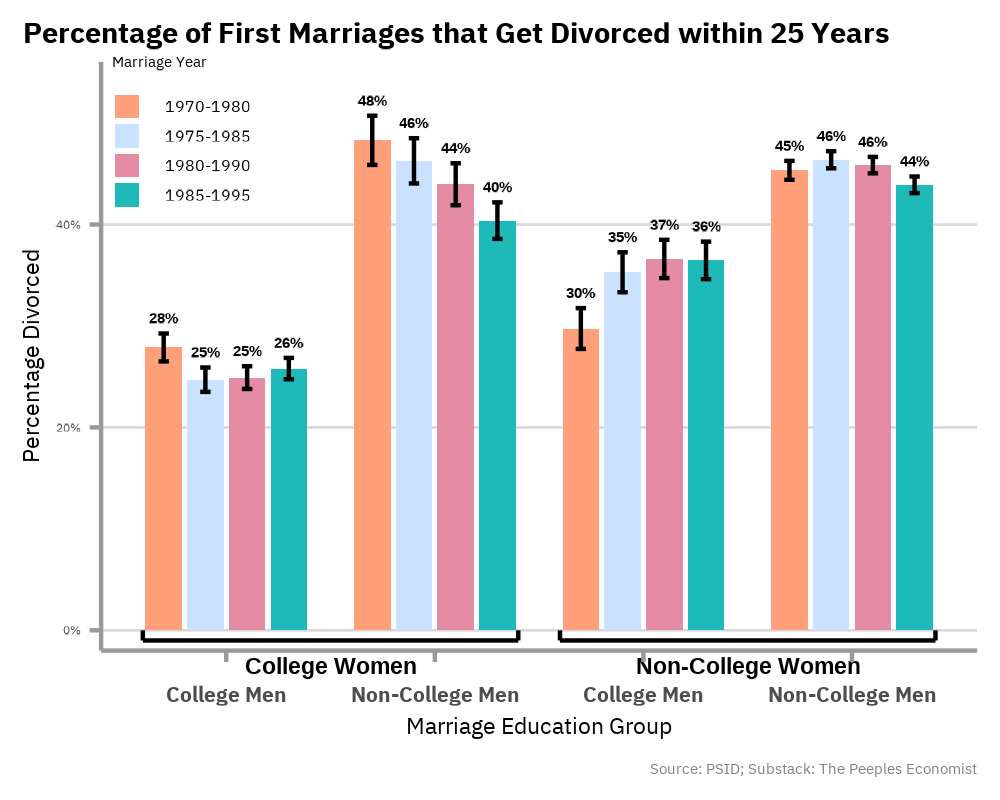

Examining marriages over time reveals the importance of education in relationships. I followed marriages beginning in different years and considered whether they ended in divorce before hitting 25 years of marriage. Among marriages starting in 1975 versus 1990, divorce rose for women without a college degree married to men with a college degree but fell for women with a college degree married to men without a college degree. Sociologists see the same pattern for income.

The Role of No-Fault Divorce Laws

Economists and sociologists have proposed several hypotheses regarding the divorce divide: the age at first marriage is higher for adults without college degrees, birth rates have actually decreased less for college-educated adults than for non-college-educated adults in recent years, and the type of people becoming educated in 1980 is significantly different from today. I go into these potential reasons in detail in my Substack post.

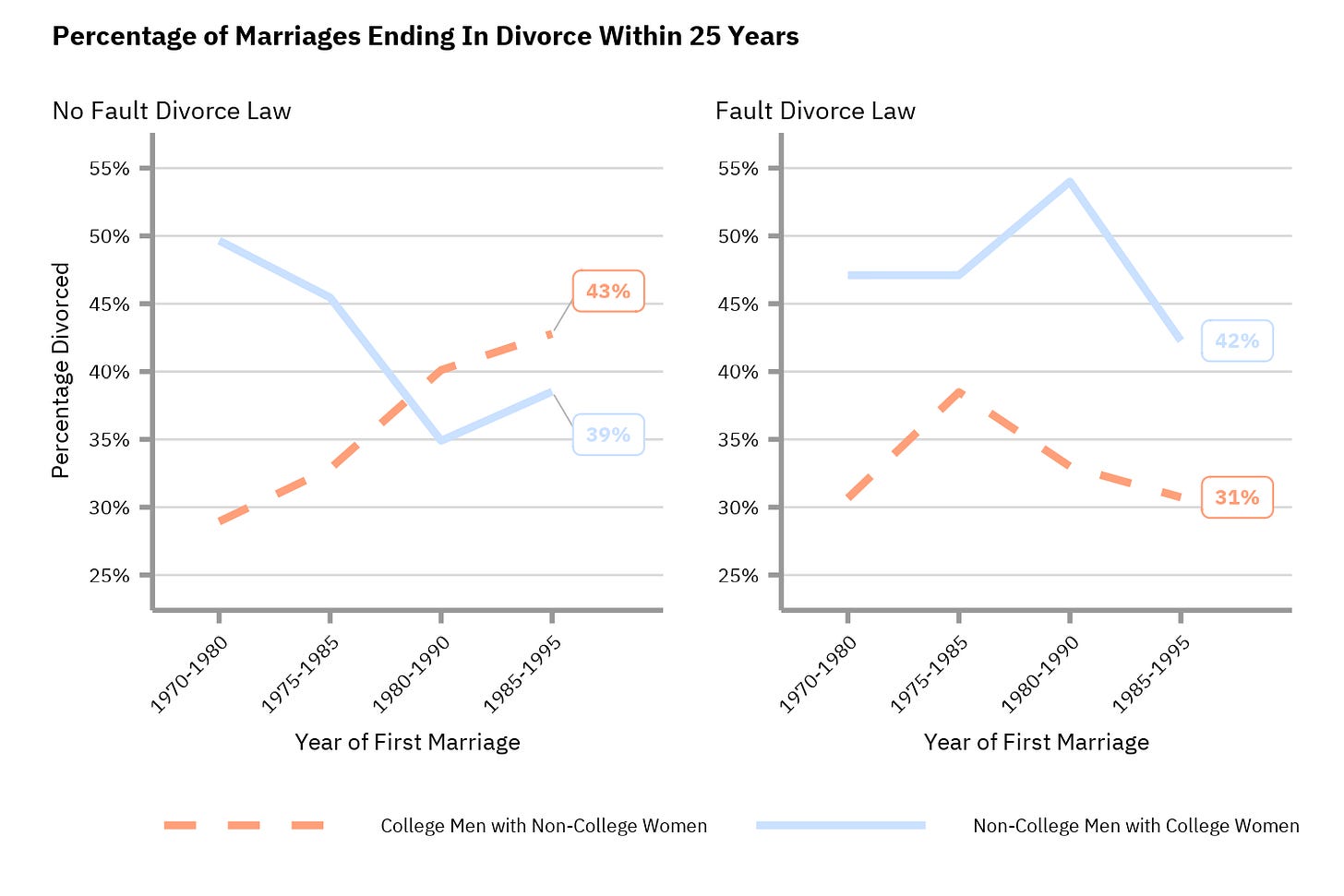

However, in the late 1960s, the U.S. began shifting from “fault” divorce laws to “no-fault” divorce laws. Under the old system, both spouses had to agree, and one often had to blame, leading couples to fake allegations. Divorce was especially hard if one spouse resisted. No-fault laws ended these issues: spouses no longer had to point fingers. In my working paper (and Substack post), I show this change made divorce easier for women without college degrees but may have discouraged college-educated women from divorcing. I am not the only one who found the pattern below.

How This Relates to Economics

Economic research argues that an increase in income should lead to an increase in divorces, as the economic benefits of marriage decrease. Take two women: one in a low-wage job without a degree, the other a well-paid professional. For the poorer woman, marriage can bring significant economic benefits, such as shared housing and pooled income, which ease financial strain. For the wealthier woman, those gains matter less since she already enjoys comfort and independence. If either of these women falls out of love with their husbands, it is easier for the wealthier woman to get a divorce.

The divorce divide (and even marriage divide) has implications for income inequality; children who have divorced or single parents have a harder time making more income over their lifetimes. This is known as upward mobility. A paper also found that no-fault divorce laws could lead to worse outcomes for children’s lifelong earnings. On the flip side, no-fault divorce laws led to decreases in suicides for women and domestic abuse for everyone.

The Bottom Line

Some state legislators have recently introduced bills to bring laws closer to fault-based divorce once again. Texas is currently considering a bill that would eliminate its no-fault divorce reason, known as “insupportability,” and Tennessee has passed a bill that makes divorce fault-based for covenant marriages. Oklahoma has a bill to repeal its no-fault divorce law, which is currently stalled but still under consideration. Given that overall marriage rates and divorce rates have already been in decline for years, any positive benefits of these laws may be overshadowed by the restrictions placed on lower-income women having the ability to get a divorce – divorce does not always lead to bad outcomes.

About the author

Jordan Peeples, PhD is a VP Quantitative Modeling Analyst at a Fortune 500 bank. She holds a Ph.D. in Economics (2025) from the University of Pennsylvania and an MA/BA in Economics (2019) from the University of Georgia. She was born and raised in a small, rural area called Pike County, Georgia. Her posts address topics related to labor markets, demographics, and government spending.

I suspect that if such laws are pushed through there could be a decline in marriages, i doubt it would be significant. Marriage isn't seen as a necessity anymore. Very insightful newsletter! It is always interesting to see how policies cause new types of trade offs. This is obe of them.