How Much Would You Pay to Avoid Different Political Views Than Your Own?

America has become increasingly polarized, and new research shows just how far that polarization reaches: many of us are willing to pay to avoid interacting with people who hold different political views.

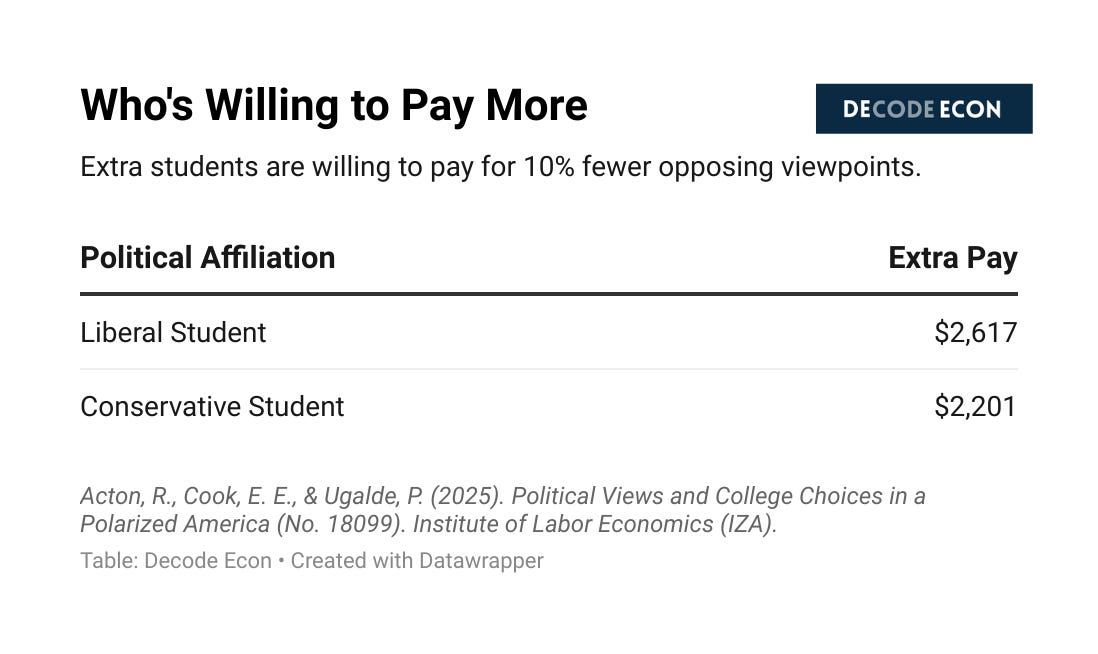

A new working paper by Riley Acton (Miami University), Emily Cook (Texas A&M), and Paola Ugalde (LSU) considers the role of politics in one of life’s most consequential decisions: where to attend college. The authors find that students are willing to pay more than $2,000 extra in tuition to attend a campus where fewer students hold opposing political beliefs.

When discussing the cost of college, we typically consider tuition, room and board, and the expense of textbooks. But this study suggests students are increasingly willing to pay for something much less tangible: avoiding political disagreement. This isn’t just a liberal or conservative issue. The study reveals something surprising for both sides.

The Study

The research unfolds in two parts:

Trends over time – a snapshot of college students’ political views from the 1980s to today.

A survey experiment – testing current students’ preferences for the political climate of a college’s state and student body.

The Experiment

Students were presented with profiles of hypothetical colleges. Each profile included information about academics, location, cost, and the political makeup of the student body.

The results:

Liberal students would pay $2,617 more to attend a college with 10% fewer conservatives.

Conservative students would pay $2,201 more to attend a college with 10% fewer liberals.

Liberals are willing to pay more to attend campuses with more liberals and fewer conservatives.

Conservatives don’t pay extra to be around more conservatives; they mainly pay to avoid liberals.

That willingness to pay is roughly equivalent to the premium students place on higher academic quality or a shorter distance from home.

This is evidence of what political scientists refer to as affective polarization. Students aren’t simply attracted to like-minded peers; they’re willing to pay to avoid those who disagree with them.

Four Decades of Polarization

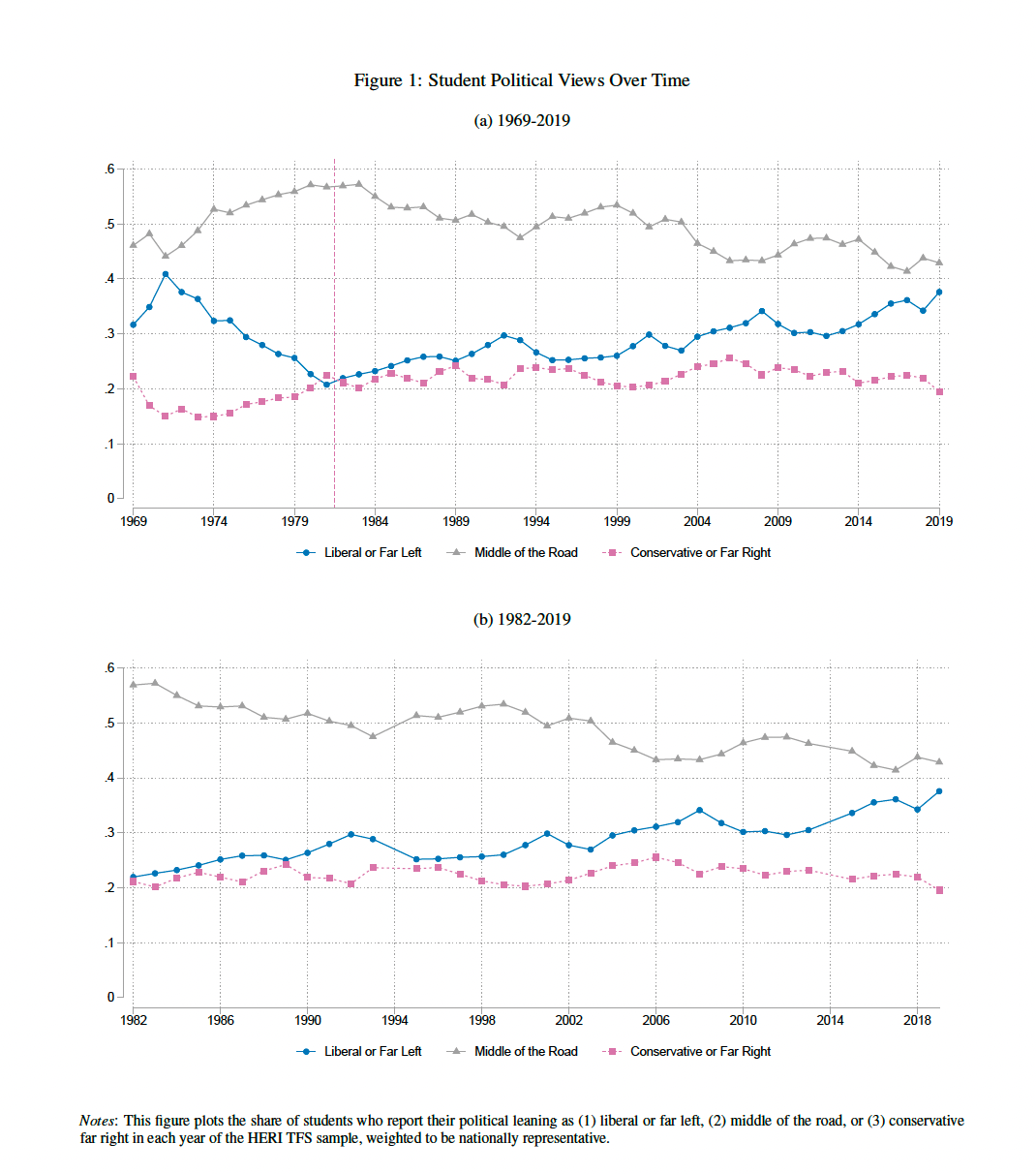

As the chart below shows, the 1970s saw a sharp decline in students identifying as liberal, mirrored by a rise in those identifying as conservative or “middle of the road.” By 1982, liberals and conservatives converged at roughly 21–22% each.

But the trajectory shifted after that:

Since the early 2000s, the share of students identifying as liberal has steadily risen, reaching 37.6% by 2019.

The share of conservatives has remained fairly stable, at about 19.5% in 2019, close to its 1982 level.

What has really changed is the decline in students calling themselves middle of the road, falling from 56.9% in 1982 to 42.9% in 2019.

In other words, it’s not that conservatives are disappearing; it’s that the political “middle” is shrinking, and more students move toward the liberal side.

Other findings include:

Elite schools have shifted the most to the left. By 2019, more than half of students at the most selective colleges identified as liberal, compared with about a third at other schools.

Religious colleges have grown more conservative.

Demographics, academics, or geography can’t explain these divides. Politics itself is reshaping where students enroll.

This long-run polarization helps explain why politics has become such a powerful factor in college choice today.

Why It Matters

If students continue sorting into universities based on political ideology, the effects could reshape higher education and society:

Fewer cross-partisan friendships. College has traditionally been one of the last spaces to encounter people with different ideologies. Homogeneous campuses mean fewer opportunities to practice civil dialogue.

Deepening divides. Because political identity aligns with geography and income, this sorting could perpetuate existing inequalities.

Future leadership. Elite colleges disproportionately produce policymakers, judges, and CEOs. If these institutions become more politically uniform, the impact will extend far beyond the campus.

This research reveals that students’ own choices are now one of the most significant forces shaping the political climate of higher education. How will higher education institutions leverage this information? Will they work to increase diversity, or will they use this information to market their offerings selectively?

The Bottom Line

The U.S. is becoming more polarized, and higher education is no exception. This research shows that both liberals and conservatives are actively avoiding each other and are willing to pay thousands of dollars to make that happen.

In the 1980s, students were more likely to encounter a mix of political ideologies on campus than they are today. College may represent the last chance for many young people to experience ideological diversity before they form adult friendships, careers, and communities. The question is: what happens when that chance disappears?

Reader Question: Beyond college, do you find yourself avoiding spaces where people think differently from you?

Very insightful work. The results also suggest a deepened future divide in the composition of faculties political orientations across campuses. It is very possible that appointment decisions will be more starkly influenced by students’ self selection into like-minded academic communities.

Further, Gary Becker (1954) suggested an intuitive economic rationale for avoiding labor market discrimination. That is, discrimination does not pay off. Although an indirect association, the results of this study would propose that discriminatory hiring decision, based on political orientation, could potentially be revenue generating.

1970 in the graph looks interesting. I wonder how consistent the definitions of left and right remains over the years in this graph?

Great work!