New Evidence That Studying Economics Really Works

Back in January, I wrote a post called Why Study Economics and What Skills Actually Matter. It came from conversations I keep having with students who are anxious about the future—AI, disappearing job titles, and the fear that choosing the “wrong” major could lock them out of opportunity.

My argument then was simple: economics matters because it teaches adaptability. It trains you to reason through uncertainty when the world refuses to sit still. I also shared data showing that, on average, studying economics pays off financially over a career.

But a fair question remained:

Does that story still hold up when we look carefully at how the labor market rewards economics majors?

That’s why a new paper caught my attention, especially because one of its authors, Nicholas Moellman, is a graduate of the University of Kentucky Economics Ph.D. program. I earned my Ph.D. in economics at UK as well, and I remain deeply supportive of that program.

This new paper is a must-read for any economics instructor or student considering the field.

It provides new, rigorous evidence not only that economics majors earn more but also why.

And the answer lines up closely with the argument I made back in January.

About the Study

Title: Job Market Outcomes for Undergraduate Economics Majors

Authors: Nicholas Moellman, Danko Tarabar, Alexander Tsiukes

Access Paper: Eastern Economic Journal (2026)

Abstract:

This study examines labor market outcomes for undergraduate economics majors in the United States using American Community Survey data from 2014–2023, covering more than four million individuals ages 25–65. The authors estimate the marginal effects of holding a general, business, or agricultural economics degree on earnings and weeks worked, controlling for extensive individual, occupational, industry, and state-level characteristics. The results show a robust and statistically significant earnings premium for economics majors, particularly for general economics degrees. The premium is driven primarily by higher wages rather than increased labor supply or occupational sorting and persists throughout the life cycle and across U.S. states.

Research Question

Do economics majors earn more than comparable college graduates, and if so, why?

Is the observed earnings premium driven by working more, choosing different occupations, or by higher wages within the same jobs?

Data and Setting

Data Source:

American Community Survey (ACS), 2014–2023

Sample:

~4.5 million college-educated individuals

Ages 25–65

All 50 U.S. states

Key Comparisons:

Economics majors vs. non-economics college graduates

Degree types: general economics, business economics, agricultural economics

Key Advantage:

Rich microdata allow controls for occupation, industry, geography, education level, and demographics

Enables separation of wage effects from labor supply and occupational choice

Methodology

Log-linear earnings regressions with extensive controls

Ordered probit and linear probability models for weeks worked

Fixed effects for state, year, occupation, and industry

Separate analyses by gender and labor force participation

Life-cycle analysis using predicted age–earnings profiles

Geographic analysis of earnings premia by state

Main Findings

1. Economics Majors Earn More—Consistently

General economics majors earn 5.7–8.5% higher wages than comparable college graduates

The premium is strongest among individuals in the labor force

Earnings gains are similar for men and women in general economics

2. The Premium Is Not About Working More

No evidence that economics majors work more weeks per year

Differences in labor supply explain little of the earnings gap

Conclusion: the return operates through wages, not hours worked

3. Occupational Choice Explains Less Than You Think

Economics majors are more likely to work in analytical and managerial roles

However, controlling for occupation and industry does not eliminate the earnings premium

Economics majors earn more within the same occupations

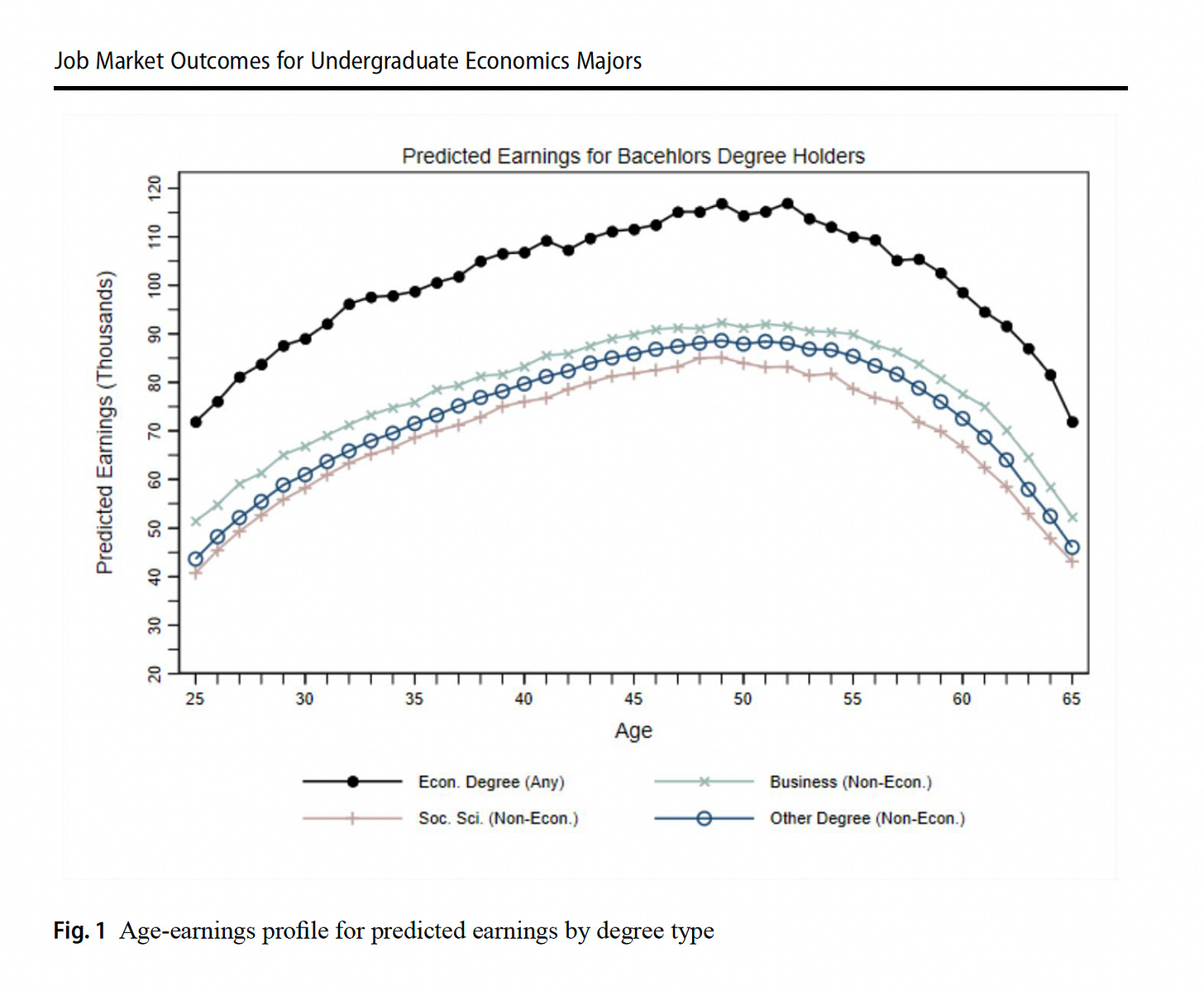

4. The Advantage Persists Over the Entire Career

Age–earnings profiles show a persistent premium from early career through retirement

This is not a short-term boost tied to first jobs or early sorting

Economic skills appear to compound over time

5. The Premium Is National, Not Regional

Positive earnings premia exist in every U.S. state

Magnitude varies, but no state shows a negative premium

Post-pandemic changes alter the size, not the direction, of the effect

Core Contribution

The study shows that economics provides a durable labor market advantage that is not driven by longer hours or a narrow job pipeline, but by higher wages within occupations. This supports the interpretation of economics as a form of general human capital—training decision-making, analytical reasoning, and adaptability rather than task-specific skills.

In short, economics does not just open doors early in a career; it raises the value of work throughout a lifetime.

Absolutely true. I didn’t work in economics and I graduated in Engineering, then later Medical Field, but the year of economics courses I took in college gave me the most understanding of how to understand the dynamics of the job market, the direction of the economy, and how to predict behavior and responses on both micro and macro scales. It shaped my thinking.

I have compared earnings with my fellow college grads in the past and i was always the top earner. I hadn't thought much about it until i interviewed for my new role and my VP said he was looking for people like me. Economics makes a difference