Inflation Fell. So, Why Do Older Americans Feel Worse?

A little bias explains a lot.

Headline CPI data released last week reports that inflation is now 2.4%. This is much closer to the 2% target set by the Federal Reserve and to what we have been accustomed to as an acceptable inflation level. But that is not the story.

A recent Marketplace segment highlighted a new trend. Consumer confidence just collapsed to its lowest level since 2014, according to the Conference Board.

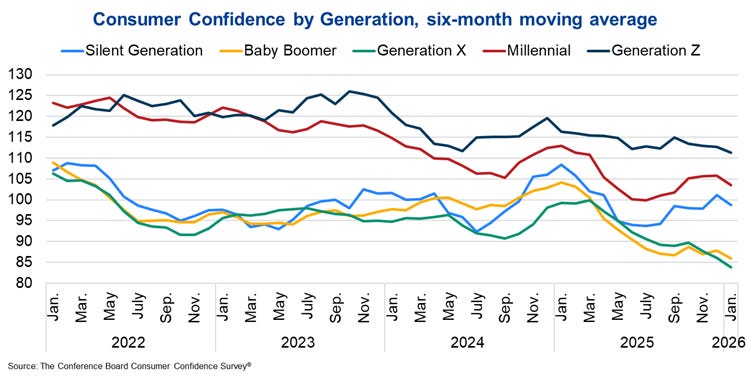

The headline number fell sharply in January. But the real story isn’t just that confidence fell; it’s who is losing confidence the fastest.

Older Americans are struggling with their economic outlook. Gen X, baby boomers, and even the Silent Generation saw much steeper drops in confidence than younger consumers. Meanwhile, Gen Z remains, somehow, the most optimistic group in the survey.

So what’s going on? Why are older Americans so much grumpier about the economy?

The Economics Behind the Grumpiness

At first glance, this doesn’t make sense. Here is the Decode Econ perspective.

Inflation is lower than it was. Wages have risen. Unemployment remains historically low. Many older Americans are in their peak earning years or already retired with assets that have benefited from strong markets.

Yet confidence is cratering, providing more evidence of the Vibecession—the disconnect between economic indicators and consumer sentiment.

The Economics: Prospect Theory and Reference Points

To understand this, we have to leave traditional macroeconomics and enter behavioral economics.

In 1979, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky introduced prospect theory. The core insight is simple but powerful. People don’t evaluate outcomes in absolute terms. They evaluate them relative to a reference point.

Reference point bias, rooted in prospect theory, is a cognitive bias in which individuals evaluate outcomes relative to an arbitrary, subjective baseline rather than their absolute value.

Older consumers don’t just experience prices as they are today. Because of their experience, they can compare today’s prices with what they used to be. A $24 entrée doesn’t feel like “normal inflation”, it feels like a personal insult if you remember paying $14 for the same meal ten years ago.

As one economist interviewed by Marketplace put it, inflation can feel like

“someone punching you in the face and taking a couple of $20 bills,”

even if your income technically kept up.

Real vs Nominal

The emotional experience is coded as a loss relative to a mental baseline. That baseline isn’t real, inflation-adjusted income. It’s the nominal price of milk, gas, or rent from ten years ago. So even though real incomes have increased, many older Americans remain anchored to nominal prices. And higher sticker prices feel like a decline—even when real purchasing power hasn’t fallen.

Younger consumers don’t have that same anchor. If rent has always been expensive during your adult life, it doesn’t feel like something was taken from you. It feels normal. That difference in reference points creates a very different emotional response to the same economy.

Now layer in something else from prospect theory: loss aversion.

Repeated price increases feel like repeated losses. Gas. Groceries. Dining out. Insurance premiums. The experience of daily, repeated expenses is a reminder of price changes and is most likely to trigger emotional responses.

Even if real income recovers, the memory of the loss lingers. Behavioral research shows that losses stick in our minds longer than gains.

The Bottom Line

Consumers over 35 account for a large share of total spending. If they pull back because they feel worse, even when the data says they’re okay, economic growth slows.

That’s the lesson here: Economic outcomes depend as much on perceptions as on paychecks. Vibes matter!

Inflation doesn’t need to be high to damage confidence. It only needs to feel like a loss relative to what you expected. Older Americans aren’t irrational. They’re human, and they are falling for reference point bias.

If policymakers want to restore confidence, it won’t be enough to show charts about declining inflation. They have to understand reference points. They have to understand loss aversion. That is one way to tackle the affordability crisis.

Ooooh, I wonder how the changing demographics structure over the past few decades (more old people compared to young people) affects overall inflation expectations? They may be more sensitive now. Interesting article!

One lesson of the Pandemic was the poor word choice of "Transitory" when referencing inflation. Classically defined as "Temporary or Short-lived", transitory gave the impression that it would end in months not years. The Comms teams for the White House and Treasury should never have agreed to the term being utilized repeatedly.

Implicit bias entered the conversation when people didn't feel they were as affected by inflation as they "believed" their neighbor to be. Political leaning dragged in the "Halo Effect" where they gave to much credance to leaders based on deference to educational background. (Slightly different from Authority Bias where they trust the leader implicitly.) "Horn Effect" is the opposite where you hold that same person accountable for their poor judgement/statement.

*Thanks for today's article... This Behavioral Economist loves when people take an interest in the work of others in the field!