Reshoring Takes Different Forms, Each With Its Own Tradeoffs

Reshoring is having a moment in the United States. It shows up in headlines, policy speeches, and industrial strategy plans. Often framed as a simple goal: bring jobs back home.

When politicians and business leaders talk about reshoring, they usually mean one thing: moving manufacturing back to U.S. soil so production and employment happen domestically.

But that’s only part of the story.

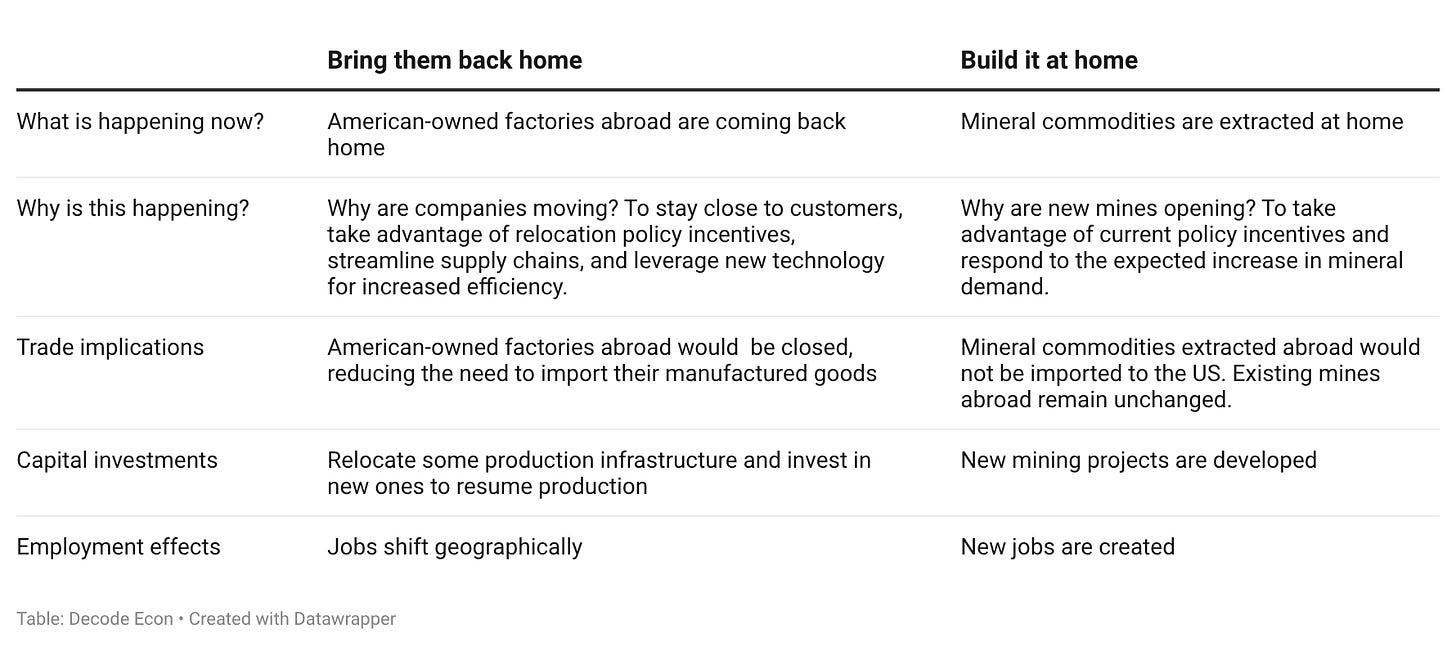

There’s an important distinction in today’s reshoring debate: bringing manufacturing back versus building critical production at home for the first time. Those two ideas sound similar, but economically, they are very different.

Today, we’re going to unpack that difference and why it matters more than the slogans suggest.

GE Appliance Case Study

A familiar example of the Bring it Back Home is GE Appliances. GE Appliances brought portions of its manufacturing back to the United States, notably relocating washing machine production from China to Louisville, Kentucky, as part of its ‘zero-distance’ strategy.

This was partly driven by economic considerations, such as supply-chain efficiency, access to technologies, proximity to customers, and responsiveness to financial incentives designed to encourage companies to relocate.

But this common understanding of reshoring is not the focus of this post.

Rather, this post discusses the opening of new domestic mining operations or the expansion of existing ones, at a time when the US is seeking to reduce its reliance on imports. In this case, it is not about bringing them back home. But building it at home.

Building at Home

To illustrate this, I will consider the case of building new cobalt and nickel mining projects or expanding existing ones. Reshoring, in this context, means that, rather than importing more nickel from abroad, the US would mine existing, proven domestic reserves.

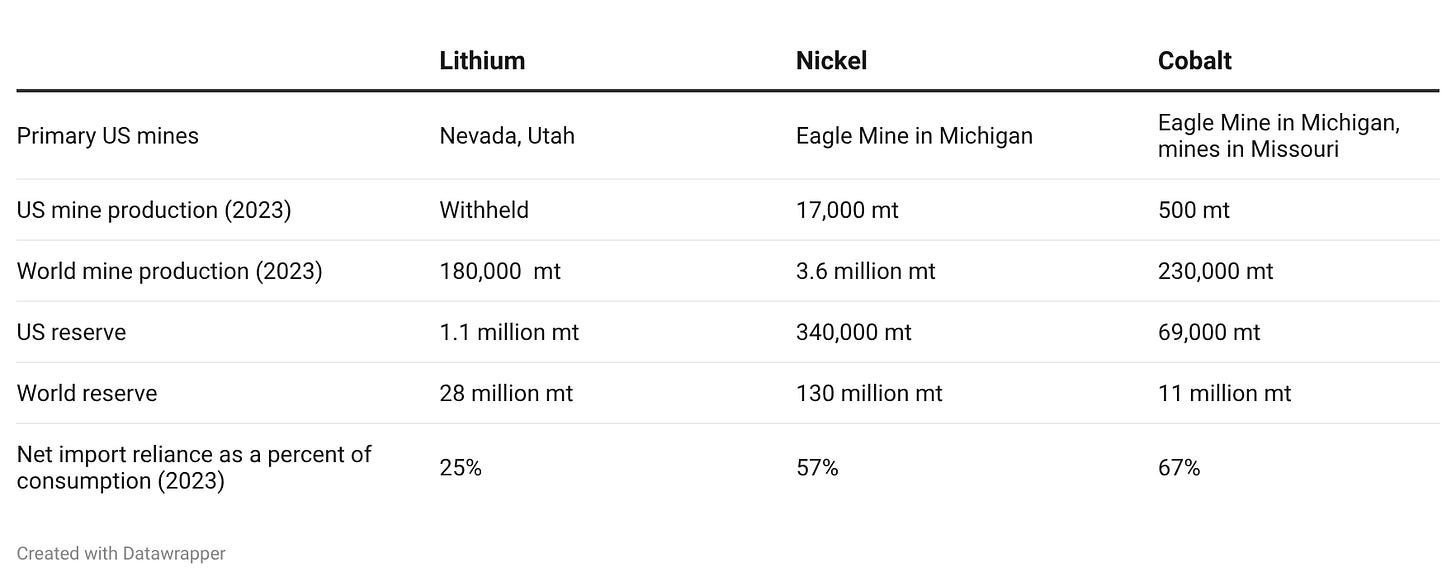

Examples of reshoring in this context include the development of nickel and cobalt projects in Missouri (US Strategic Metals), construction of lithium mining projects in Nevada (Thacker Pass), and nickel and cobalt projects proposed in Minnesota (e.g., Talon Metals and Twin Metals Minnesota).

Building Mines At Home Reduces Import Reliance

The US is historically a net importer of most mineral commodities. Importing typically reflects a lower opportunity cost of extraction in another country, owing to factors such as geology, labor costs, regulatory stringency, and existing infrastructure.

Currently, only about 43% of the nickel the US needs is sourced from domestic mines, primarily the Eagle Mine in Michigan, which accounted for all of the US mine production in 2023.

Similarly, only a handful of mines accounted for most of the 500 metric tons of cobalt mined in 2023. From 2020 to 2023, the nation’s reliance on cobalt imports declined from 76% to 67%, in part due to reshoring initiatives. Despite this decline in import reliance, 67% reliance on imports still means that most of the cobalt we need is imported from abroad.

Why Should We Care Where It Is Mined?

While choosing to mine locally could reduce import dependencies, it also addresses non-efficiency-related policy goals, such as ensuring a stable supply of raw materials (despite the cost) that key economic sectors and national security critically depend on.

Reshoring also offers other benefits. Domestic mining creates local jobs, generates tax revenues, and often does so in rural areas where economic opportunities can be limited.

However, mining is a resource- and capital-intensive activity, and it is often subject to lengthy permitting timelines. These constraints make it a costly and high-risk investment. If domestic mining operations expand before scale and efficiency are fully achieved organically, local metal prices could increase. Those higher input costs in turn could feed directly into higher prices for battery materials and other consumer goods that rely on nickel, cobalt, and other mineral commodities. This is more likely to happen with mandate-like mineral import restrictions and strong support for development projects.

Domestic mining may also face challenges in the short run, including a lack of a trained workforce and insufficient mineral-extraction technologies. There is also a need to develop domestic processing facilities to refine extracted minerals locally rather than sending them to mineral-processing hubs abroad.

Reshoring also requires proper management of the environmental impacts of mining and processing operations. When these activities relocate, pollution impacts also move with them. Hence, we need stronger environmental guardrails as a necessary prerequisite for reshoring.

The Bottom Line

The key takeaway is straightforward: reshoring mining entails trade-offs that people deeply care about.

Understanding these trade-offs clarifies why prices may rise, why jobs may grow, and why environmental policy becomes central rather than peripheral to reshoring initiatives. This perspective enables us to move beyond reshoring rhetoric and gain a deeper understanding of what reshoring mining actually delivers and entails.

Two Questions For You

As the United States seeks to reshore critical minerals, what do you think the nation should prioritize? Reducing costs? Environmental protection? Or local jobs? Workforce development?

How should we weigh the tradeoffs between continuing to import nickel and cobalt from countries with higher pollution risks, versus bringing those environmental costs home in exchange for greater supply security and local economic benefits?

Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

About The Author

Mahelet G. Fikru is an economist and educator. She holds a PhD in economics from Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Her posts address topics related to sustainability and innovations. If you enjoyed this analysis, you can subscribe to her M G Fikru newsletter.

A lot of people in the U.S. are too young to remember some of the environmental tragedies like Love Canal. We also forget the health costs of mining. I see the economic benefits but also the costs not just to miners but to the land.

This is a very clear and helpful framing of reshoring as a set of tradeoffs rather than a slogan — especially the distinction between “bringing it back” and “building it at home.” One additional angle that might deepen the analysis is the incentive structure that led to the current concentration of production in the first place. Since mining investments are long-lived and highly sensitive to policy stability, it would be interesting to explore whether today’s policy objectives materially change the underlying cost, risk, and credibility conditions that originally drove offshoring — and whether those changes are likely to persist long enough to sustain domestic production at scale. That intertemporal dimension seems crucial for assessing how durable reshoring efforts can be.