The 50 Year Mortgage

How to make homeownership affordable, again.

The Problem

Homeownership is slipping further out of reach. That is especially the case for the young, lower-income individuals, and those without the wealth to provide a substantial cash down payment.

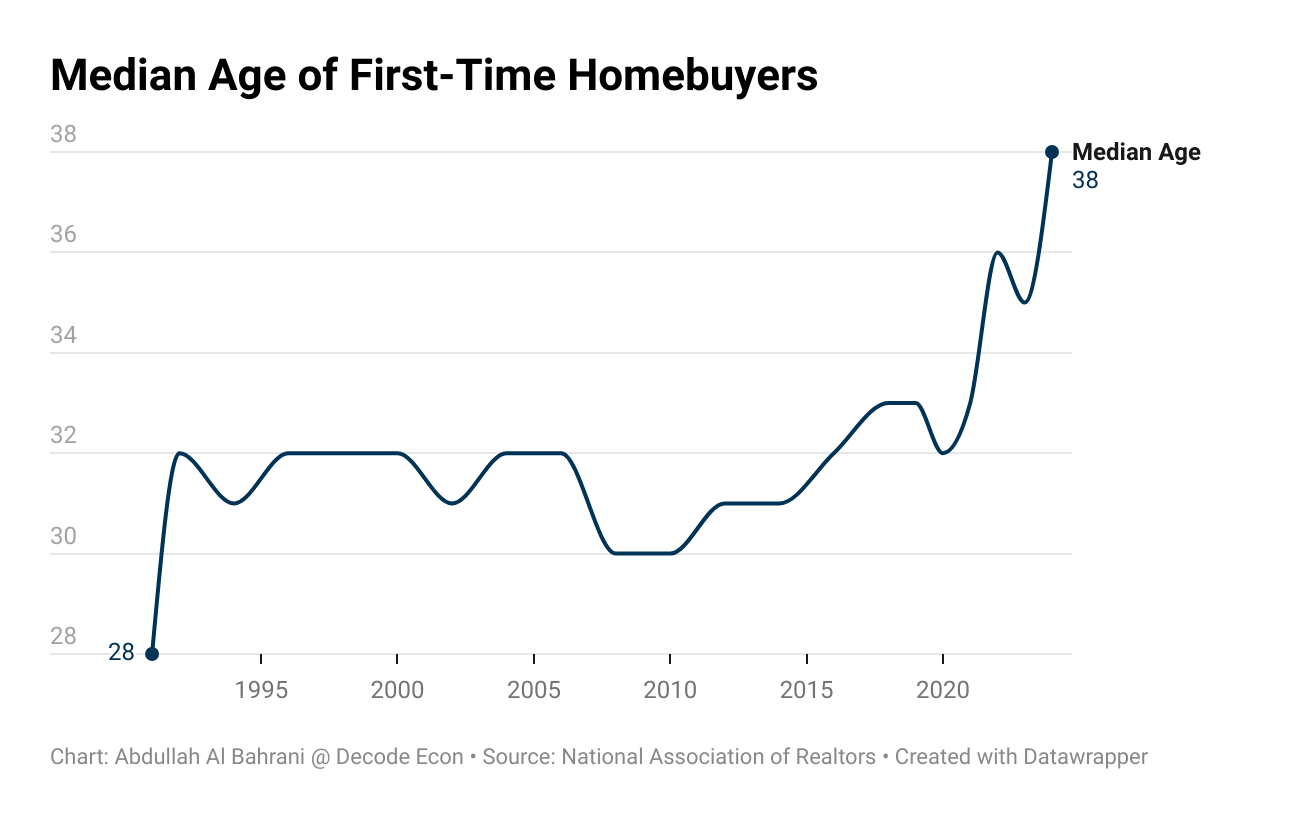

According to a recent report by the National Association of Realtors, the median price of a single-family home reached $426,800, representing a 1.7% increase from the previous year. As prices climb, the typical first-time buyer keeps getting older, now 40 years old compared with 33 just five years ago. The share of first-time buyers has fallen to 21%, the lowest level since records began in 1981.

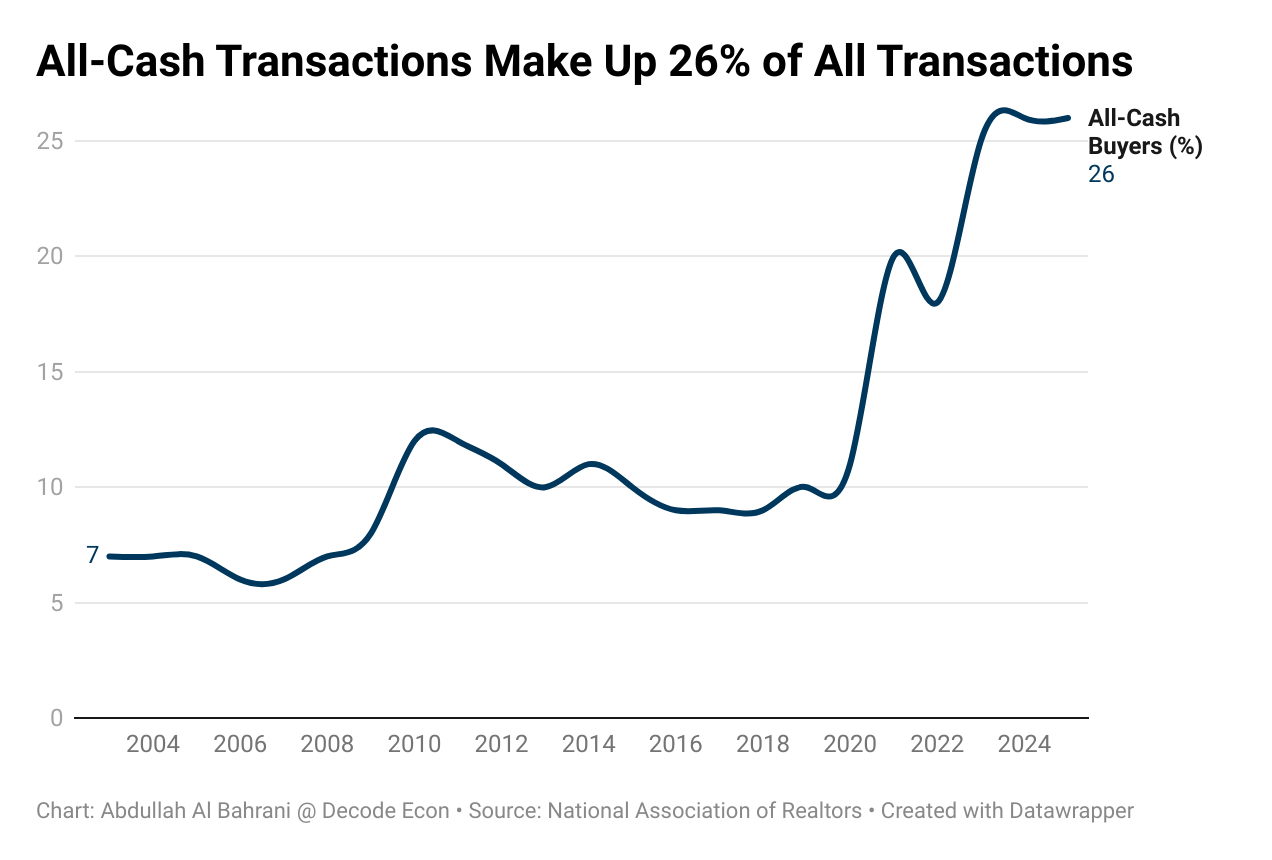

Rising prices, high interest rates, and stagnant wages have turned the American dream into a luxury good. Cash buyers now account for more than a quarter of all sales, which is up from 7% in 2003.

President Trump floated a new proposal to make homeownership more affordable. Let’s make sense of it.

The Proposal

Enter the latest proposal from Washington: a 50-year mortgage.

President Donald Trump floated the idea of a 50-year mortgage in a social media post. Federal Housing Finance Agency director Bill Pulte called it a potential “complete game-changer.” The logic is simple: longer loans mean smaller monthly payments.

The purpose of a longer-term mortgage would be to lower the monthly payment for homeowners. The longer the loan term, the smaller the monthly principal payment needed to pay the mortgage. But such a plan has other trade-offs.

The Math

Here’s the math. For a median-priced home ($415,200) with 20% down at 6.3% interest:

30-year mortgage: $2,056/month

50-year mortgage: $1,823/month

That’s $233 less per month, but at a steep cost. Borrowers would pay about 40% more in total interest and build equity much more slowly. Homeowner’s total monthly payments would total $740,160 for the 30-year mortgage, compared to $1,093,800.

The 30-year mortgage itself was once a financial innovation. It was created during the New Deal to make homeownership accessible to middle-class families. Before that, most loans lasted 5–10 years and required large balloon payments at the end of the term. The 30-year fixed loan stabilized the market, but it also set expectations that affordability could be engineered by stretching time rather than lowering prices. We have seen this “financial innovation” to make cars more affordable when the car loan market introduced with the 7-year car loan!

The Bottom Line

When I worked as a mortgage broker, and later when I taught personal finance, I always told people: never start a deal by saying,

“I’m looking for monthly payments of no more than $XXX.”

Once you do, the dealer (or lender) can adjust other terms to meet that number, often at your expense. You might drive away with the car or home you wanted, but you will end up paying thousands more than you should. The same logic applies to mortgages: focus on the total cost, not just the monthly bill.

A 50-year mortgage might make the payment smaller, but it doesn’t make the home more affordable; it just stretches the debt further into the future. Lower monthly payments can help buyers qualify today, but they also delay wealth building and keep families tied to debt for longer.

Housing affordability won’t be solved by creative financing. It will be solved by building more homes, raising incomes, and opening fairer pathways to ownership.

What’s missing from the conversation is how to build homes for people across the income distribution; that’s the real policy challenge.

Stretching the timeline might ease the pain, but it doesn’t cure the disease.

If you found this helpful, share Decode Econ with a friend who’s thinking about buying their first home. Let’s make sense of the economy—one story at a time.

When people focus on only what they are paying now bad things happen (like the rash of foreclosures spurred by adjustable rate mortgages). Between this and the new tax deduction for the interest on some new car loans, what I see is indebtedness being sold as a feature.

Not even considering the time value of money. The idea seems good but does little to help. We need more housing. Often times I wish houses were treated less like an investment, but I also understand that they are a major vehicle for wealth for a lot of people.