The Economic Case Against SNAP Work Requirements

Do work requirements work?

This is a guest post by Michael Prunka from Enough with Michael Prunka

Over the summer, Congress passed and President Donald Trump signed a tax-and-spending bill that expands work requirements for SNAP’s “able-bodied adults without dependents” and shifts more costs onto states. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that changes to SNAP alone account for roughly $180 billion of the law’s overall safety-net cuts.

After a 120-day grace period expired on November 1, states are now fully responsible for enforcing the new rules, which raise the upper age limit for work requirements from 54 to 64 and remove exemptions for veterans, the homeless, and former foster youth.

Subjecting more potential SNAP beneficiaries to work requirements will undermine the effectiveness and efficiency of one of the country’s most impactful safety net programs.

The Economics

What are work requirements supposed to accomplish?

Proponents argue that stricter work requirements will encourage more people to enter the labor force. Standard economic theory predicts that more generous safety nets reduce work incentives. But SNAP’s average monthly benefit, about $188 per person, is hardly a substitute for employment.

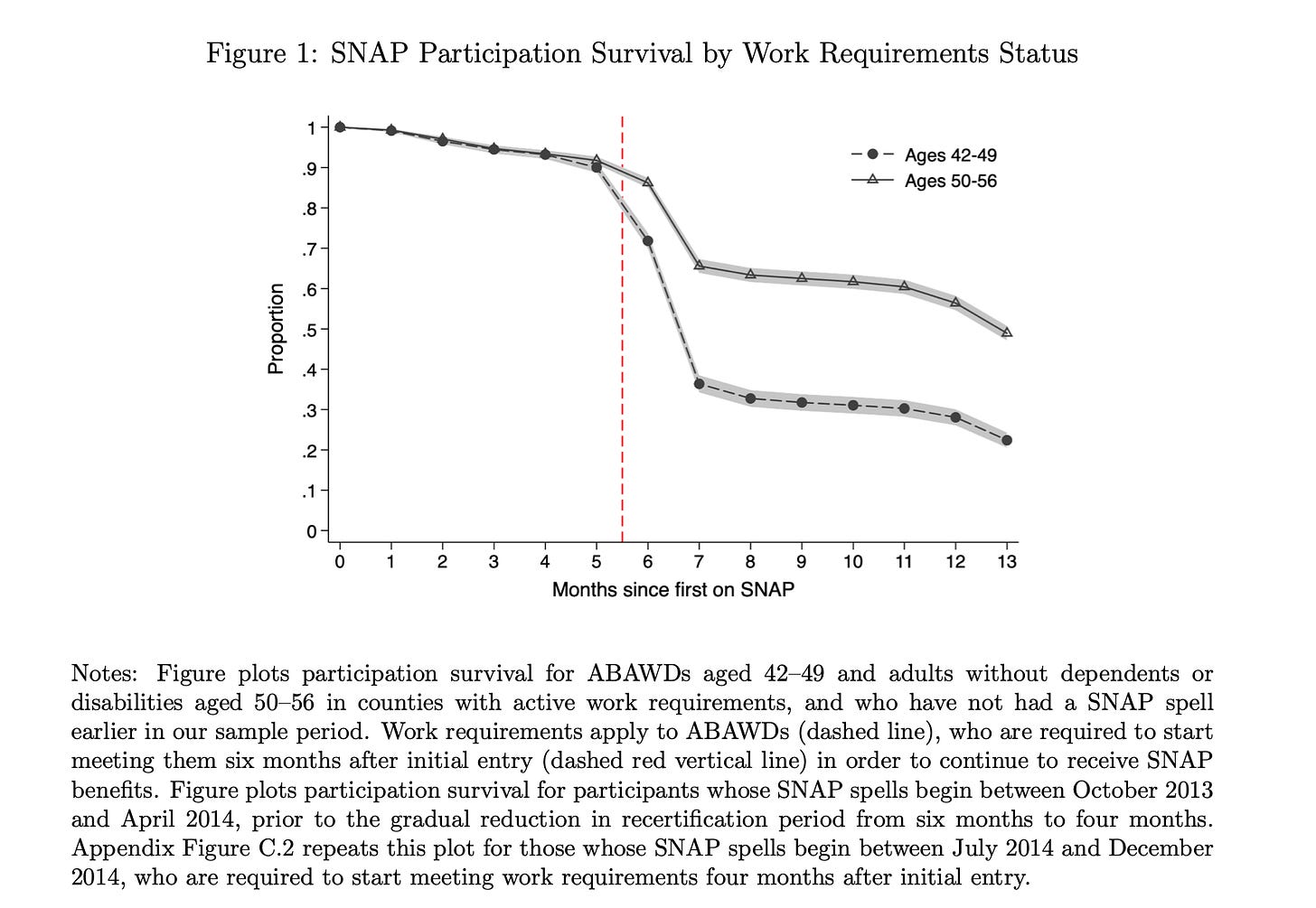

The data bear that out. A study of Virginia’s 2007–2015 policy changes found that re-imposing work requirements sharply reduced SNAP participation but had no measurable effect on employment. A separate quasi-experimental analysis even suggested that SNAP participation itself modestly increases employment and the number of hours worked.

Additionally, this notion overlooks the reality that the overwhelming majority of SNAP recipients who are able to work do so.

Inconsistent hours and cyclical employment

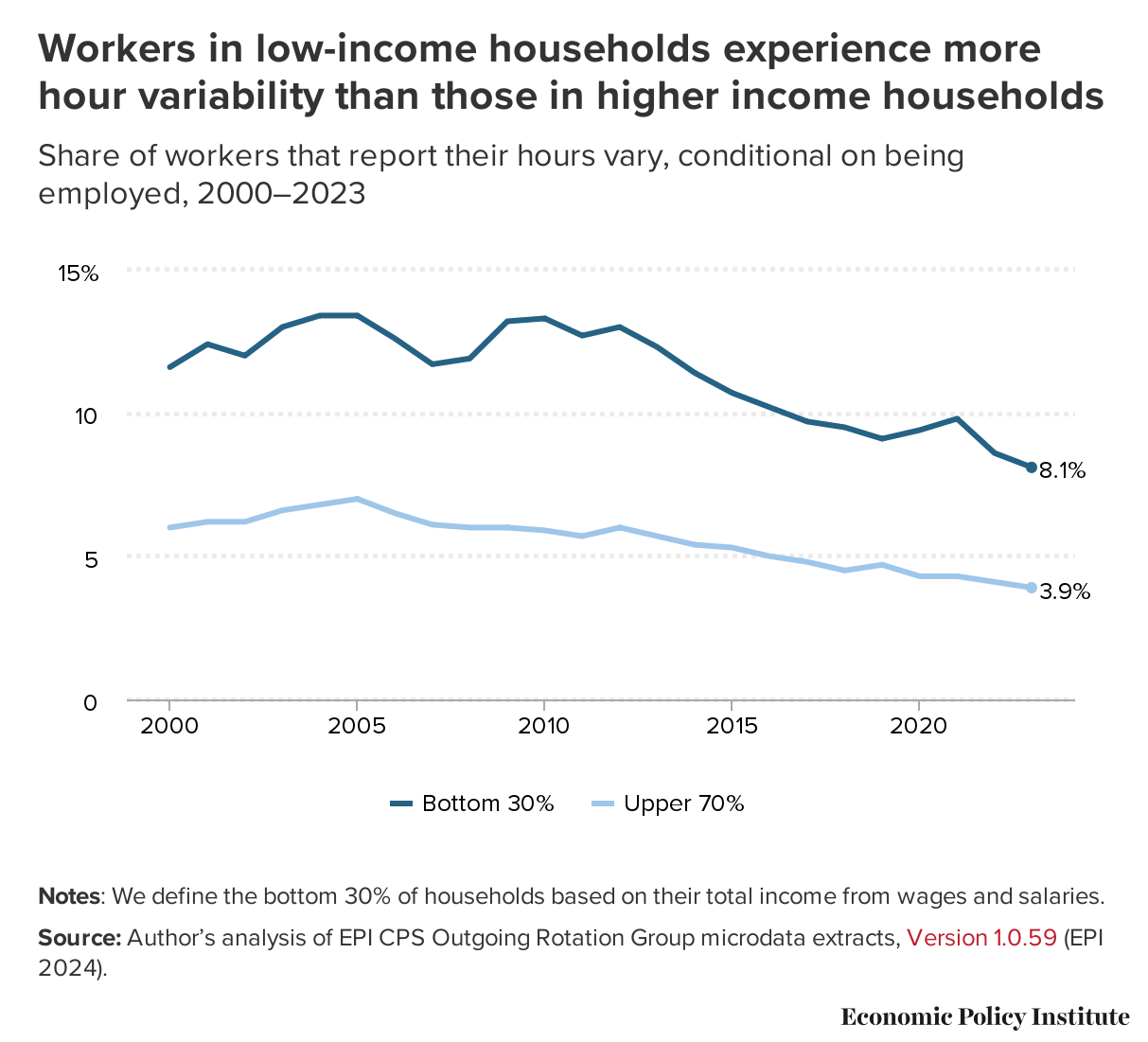

In general, hours of work are inconsistent among low-wage workers. Workers without college degrees, that’s roughly 80 percent of those in the bottom third of the income distribution, are concentrated in industries such as construction and hospitality, which are more susceptible to fluctuations in the business cycle.

Data from the Economic Policy Institute show that households in the bottom 30 percent experience double the scheduling volatility of higher-income households. That instability makes documenting steady 20-hour weeks — the benchmark for SNAP eligibility — a daunting task even in good times and nearly impossible when the labor market softens further.

Stimulating and stabilizing

The USDA estimates that SNAP generates at least $1.50 in economic activity for every dollar of benefits distributed. This happens quickly as well — 96% of SNAP benefits are spent within a month.

Because participation expands automatically during downturns, SNAP serves as an automatic stabilizer, helping to blunt recessions. However, the new law undermines that function in two ways. First, shifting costs to states that must balance their budgets will put SNAP benefits at risk during a downturn. This will disproportionately impact states that are already facing budgetary challenges and high SNAP participation rates.

Second, additional administrative barriers presented by expanded work requirements will make it tougher for people to get help when demand does surge. The stimulative impacts will be diminished and take longer to be felt throughout the economy.

The Bottom Line

Bureaucracy is expensive, and it’s not stimulative. Expanding work requirements diverts SNAP dollars from groceries to paperwork, reducing both efficiency and impact on individuals and the broader economy.

If the goal is to strengthen the labor market, the evidence isn’t convincing. If the goal is to trim the deficit, it comes at the cost of weakening one of the country’s most effective automatic stabilizers. Either way, it’s an economic trade-off that makes little fiscal sense.

Most people are just a few missed paychecks away from needing SNAP to make ends meet.

About The Author

Michael Prunka holds degrees in economics and journalism from East Carolina University. His publication, Enough with Michael Prunka , explores hunger and food insecurity through an economic lens. Subscribe to Enough if you believe no one in America should have to wonder how they’ll feed their family.

Straw man here: I live in a poor area of a poor state and have know a few people on SNAP and working full time. These are folks doing everything our society asks, their pay just isn’t enough.

I have never seen a study that shows work requirements do anything other than throw up barriers to participation, which I guess proponents cite as evidence it works, it’s chasing away those that work. My strawman stuff shows it just makes it too difficult for eligible people to navigate

It is a little dated now but back in the mid 2010s there was a study that found roughly 80% of receiptants worked. The problem is not people not wanting to work. There is no evidence it ever was.. building better entitlement and assistance programs is about listening to the people that need them.