What is Going on in Venezuela?

The Economics of Regime Change

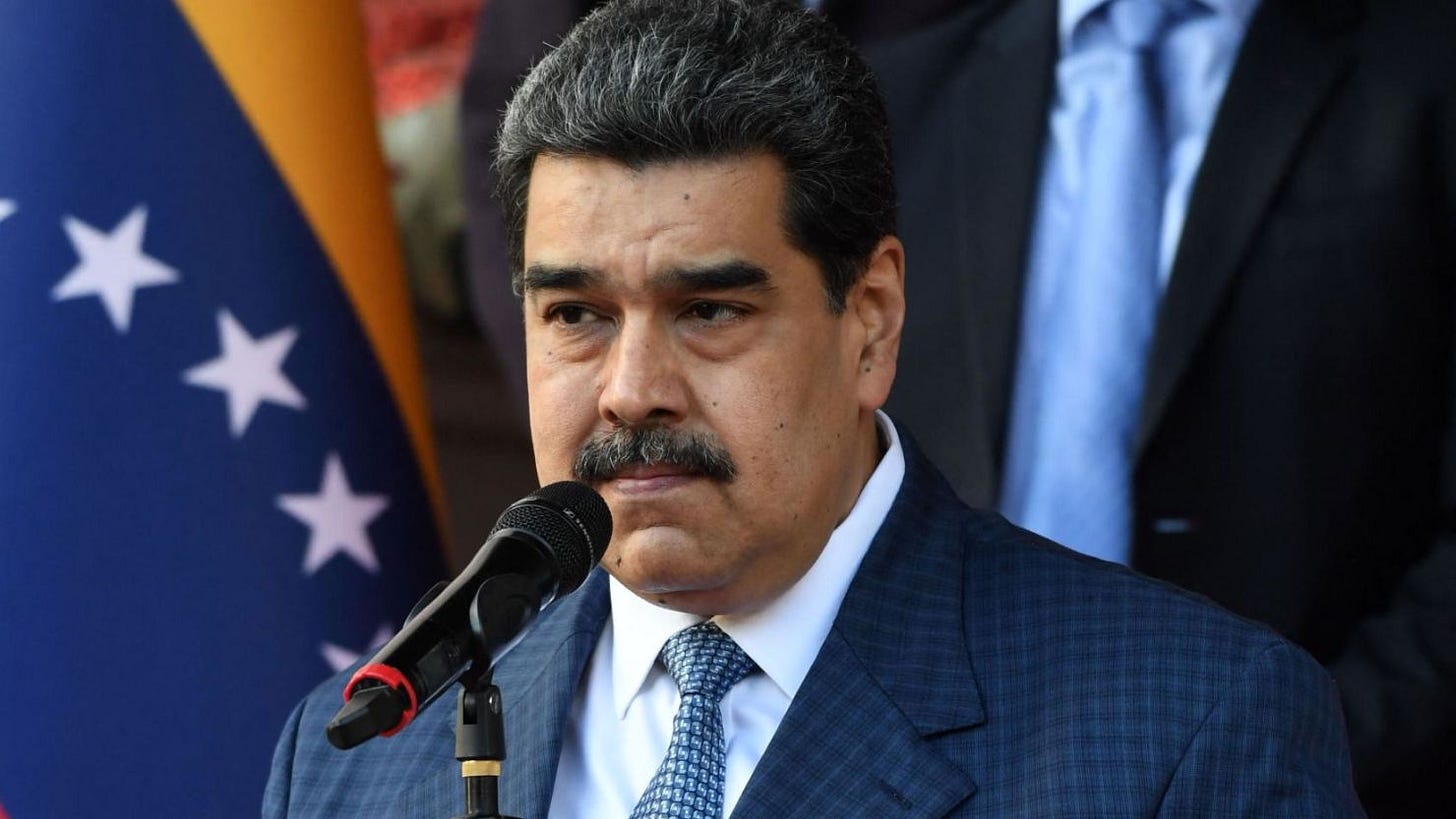

On January 3rd, 2026, the United States overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in an overnight military operation.

Maduro, 63, has ruled Venezuela since 2013. International observers widely disputed the results of his 2024 election, and the U.S. recognized the opposition candidate, Edmundo González, as the legitimate winner. Sanctions followed. Despite that, Maduro was sworn in for a third term.

Why Capture Maduro?

The U.S. is charging Maduro and his wife with narco-terrorism, cocaine importation, and weapons conspiracies as part of a campaign against alleged drug trafficking by his government. U.S. officials claim Maduro led a “narco-state,” protecting cartels like the Sinaloa Cartel in exchange for profits, and is now being held to face these federal charges in New York.

U.S. Public support for intervention was weak. A CBS News poll from November found that 70% of Americans opposed military action in Venezuela, and 75% believed Congressional approval would be required. Most respondents also said Venezuela does not pose a major threat to the United States.

What is clear are the charges and the intervention itself. What remains contested are its motivations and the likely long-term consequences.

For and Against Intervention

Opponents of the intervention are concerned that the intervention is primarily about access to oil. This view relies on President Trump’s statement at Saturday’s press conference that the U.S. would “run” Venezuela temporarily during the transition and “get the oil flowing.” They also point out that Trump ordered the operation to capture Maduro just a few weeks after pardoning former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández, who had already been convicted in a U.S. court on similar drug trafficking charges. Additionally, they raise concerns that Congress was not involved in the decision to invade Venezuela.

Proponents of the intervention and regime change believe it will improve the lives of Venezuelans who have been under the control of Maduro’s policies. Viewed as an authoritarian dictator, his policies contributed to a severe economic and humanitarian crisis, leading to hyperinflation, shortages of basic goods, and the displacement of millions of Venezuelans as refugees. The economic situation has been difficult for several decades, but has been particularly severe since 2013, when Maduro took office. His policies have caused an estimated 20% of citizens to flee the country.

So the natural question is one economists rarely get asked directly:

What are the economic consequences of regime change?

Foreign policy debates often focus on intentions and legality. Economics asks a different question: what actually happens after regimes are forcibly changed?

It turns out, economists Samuel Absher, Robin Grier, and Kevin Grier asked that exact question.

The Economics

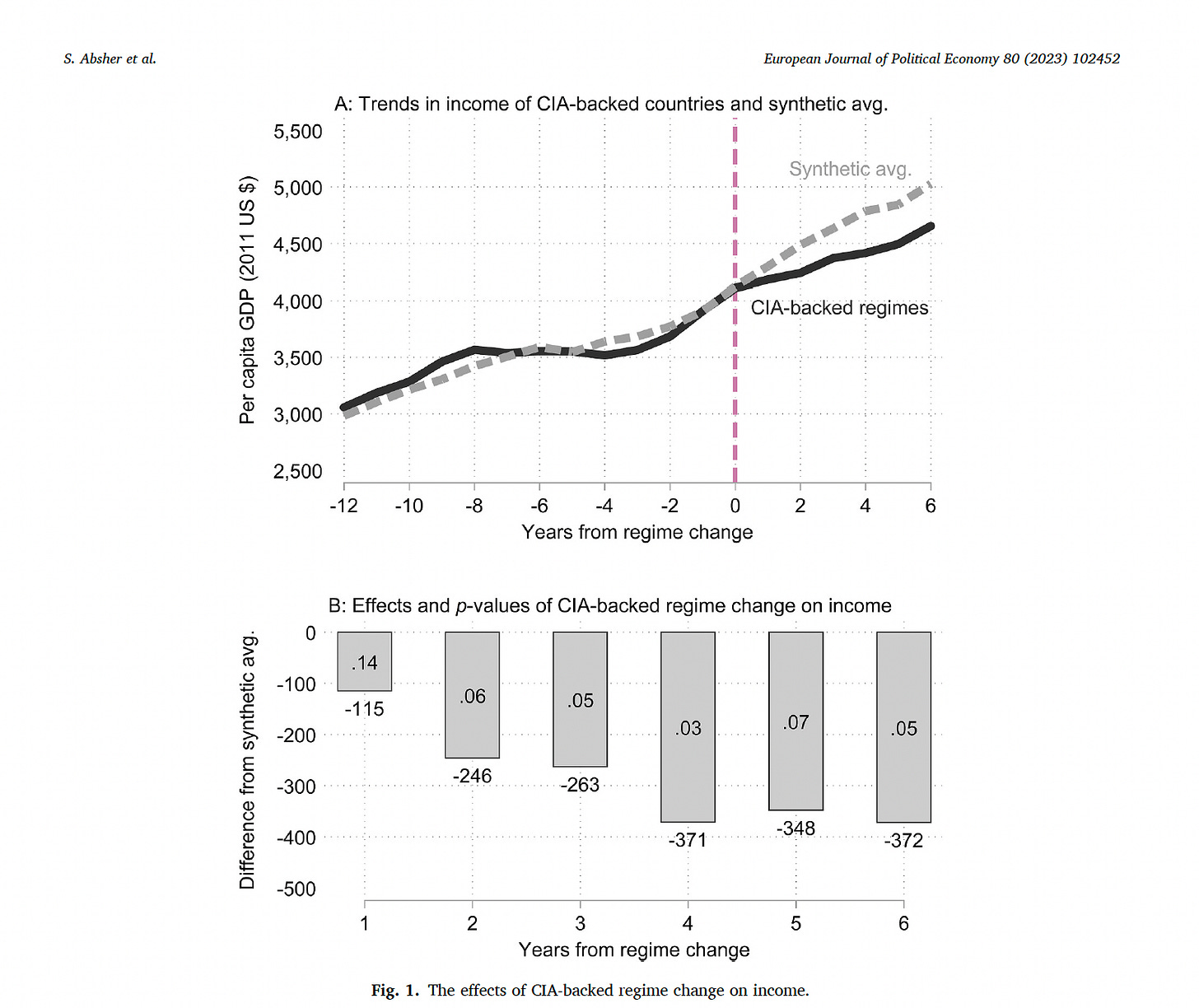

In a 2023 paper published in the European Journal of Political Economy, Absher, Grier, and Grier examine CIA-sponsored regime changes in Latin America during the Cold War. Using a synthetic control method, they compare countries that experienced U.S.-backed regime change (Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, and Panama) with what would likely have occurred absent the intervention.

This analysis does not judge whether the intervention is morally justified. It evaluates what past interventions have produced economically and institutionally. Venezuela in 2026 is not Latin America in the 1960s, but the economic mechanisms, uncertainty, weakened institutions, and disrupted investment remain remarkably consistent across time and place.

Their findings are striking:

Income fell: Five years after regime change, real GDP per capita was about 10% lower than the counterfactual.

Democracy collapsed: Democracy scores dropped sharply and stayed depressed for years.

Civil society weakened: Large declines in:

Rule of law

Freedom of expression

Civil liberties

These weren’t small or temporary effects. The political damage was immediate and persistent, and the economic damage grew over time.

One important detail: these were not failed states or economic disasters before intervention. In fact, the authors show the CIA often intervened in countries that were more democratic and economically better off than others in the region.

The mechanism is familiar to economists:

Political instability raises uncertainty

Uncertainty discourages investment

Weak institutions reduce long-run growth

In economics, uncertainty is not neutral. It changes behavior, delaying investment, slowing growth, and eroding institutional trust long before policies are fully implemented. Regime change, even when framed as stabilization, often undermines the very institutions that support economic development.

The Bottom Line

Regime change is not just a foreign policy decision; it’s an economic shock.

History suggests that externally imposed regime change tends to:

Make countries poorer

Less democratic

More institutionally fragile

That doesn’t mean Maduro’s regime was economically sound or morally defensible. But the evidence is clear: overthrowing governments is far more likely to destroy economic capacity than rebuild it.

Economics doesn’t tell us what policies should be morally chosen. But it does help us understand tradeoffs. The trade-off is stark: Regime change may satisfy short-term political goals, but the long-term economic costs are often borne by those who had the least say in the decision.

What to Expect Next

For Venezuelans, the future will be determined by how quickly a new government is established and by the policies the government implements during the transition. Delcy Rodríguez is the current interim president, appointed following the intervention. Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado, who recently won the Nobel Peace Prize, has called for Edmundo González, to be recognized as the rightful leader of the nation. He was widely regarded as the legitimate winner of the country's 2024 presidential election.

The key economic question now is not who governs Venezuela, but how quickly uncertainty can be reduced and credible institutions rebuilt.

For now, there will be uncertainty. That’s the economics of regime change.

Further Reading

If you want a non-academic but influential account of how economic and political pressure can be used alongside, or instead of, military force, I recommend Confessions of an Economic Hit Man by John Perkins.

The book offers a firsthand account of how debt, development loans, and economic leverage have shaped political outcomes in developing countries. While it is not an academic study and should be read critically, it raises important questions about power, incentives, and the hidden economic mechanisms behind regime influence.

Discussion Prompt

The research discussed in this post finds that externally imposed regime change often leads to lower income and weaker institutions. Which economic mechanism, uncertainty, reduced investment, or institutional erosion, best explains these outcomes?

This analysis evaluates economic outcomes, not moral justification. Can a policy be ethically justified yet still economically harmful? How should economists handle that distinction?

Looking ahead in Venezuela’s case, what economic indicators would you track to assess whether regime change improves or worsens economic well-being?

Everything you say is correct. And yet... Chile was a democracy when the CIA deposed Allende, but Venezuela was a dictatorship already. Moreover, Venezuela has not actually seen "regime change" -- it was the removal of a dictator. It is not at all clear what will replace Maduro. The previous Vice President, Delcy Rodriguez, has taken over as Acting President. She is not a democrat, but she has considerably more technical credentials than the bus driver. Perhaps she would be less economically incompetent. There may not be regime change at all -- what Mr Trump most appears to want is more economic competence, more cooperation with the US on oil, much less friendliness with Russia and China, and fewer Venezuelan economic refugees. So it is not clear that the study you cite is relevant. Authorization by Congress is a red herring by opponents of Mr. Trump -- the War Powers Resolution of 1973 requires that the President inform Congress within 48 hours of military action in a foreign country; troops must be withdrawn within 60 days unless Congress authorizes the action. This action is legal by US law, although international law may differ. I am gonna be eating a lot of popcorn while watching this.

Couple of questions

1) the Absher paper is based on 5 case studies, how relevant are any of those to the Venezuela case?

2) I thought "Confessions of an Economic Hit Man" was dismissed as conspiracy theory (someone told me this in Grad School), I just asked chatGPT and it seems to agree. Is it really worth a read?