What Spousal Jealousy Can Teach Us About Labor Markets

New Paper Says....

Every December, the economics profession enters one of its most unique traditions: job market season. Ph.D. candidates release their job-market papers. This is their best work, polished to signal the kind of researcher they will become. It’s one of my favorite times of the year because we get a preview of the ideas that will likely shape journals, policy, and classrooms in the years ahead. Aniket Panjwani on X is curating a list of all job-market candidates here.

This week, one paper caught my attention.

Kailash Rajah, a Ph.D. student at MIT, released a remarkable study that asks a question most labor economists have never thought to model, let alone measure:

What if a major barrier to women’s employment is spousal jealousy?

And what if this constraint is strong enough to override wages, safety concerns, and job quality?

Rajah’s job-market paper, “The Female Labor Supply Constraints of Spousal Jealousy: Experimental Evidence from India,” is one of the most innovative empirical papers I’ve read this cycle. It uses two field experiments in Patna, India, to study how much household dynamics shape women’s work decisions. The results are powerful.

Link to the paper: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Aj_KkEGLvL56kBOF4KvAN2ydbPWB3gsP/view

The Economics: Labor Supply Meets Household Dynamics

Economists tend to model labor supply as a function of wages, childcare, commute time, or job safety. But Rajah shows there is another constraint we rarely quantify: male partner behavior. Specifically, does having a jealous husband impact your workforce decisions?

Experiment 1: Does the gender composition of the workplace matter?

Roughly 1,400 women were randomly assigned to a two-week job in either a mixed-gender or a women-only workplace.

The results were striking. Women offered a women-only workplace were 46% more likely to apply and 31% more likely to show up. Providing women with a 50% wage increase barely moved the labor supply decision. When researchers improved perceptions of workplace safety, application rates didn’t change.

The effects were much stronger among women who reported jealous or controlling husbands. In other words, women’s decision to work wasn’t about the job; it was about the husband.

Experiment 2: Will households pay to avoid male coworkers?

Sample: 210 married women

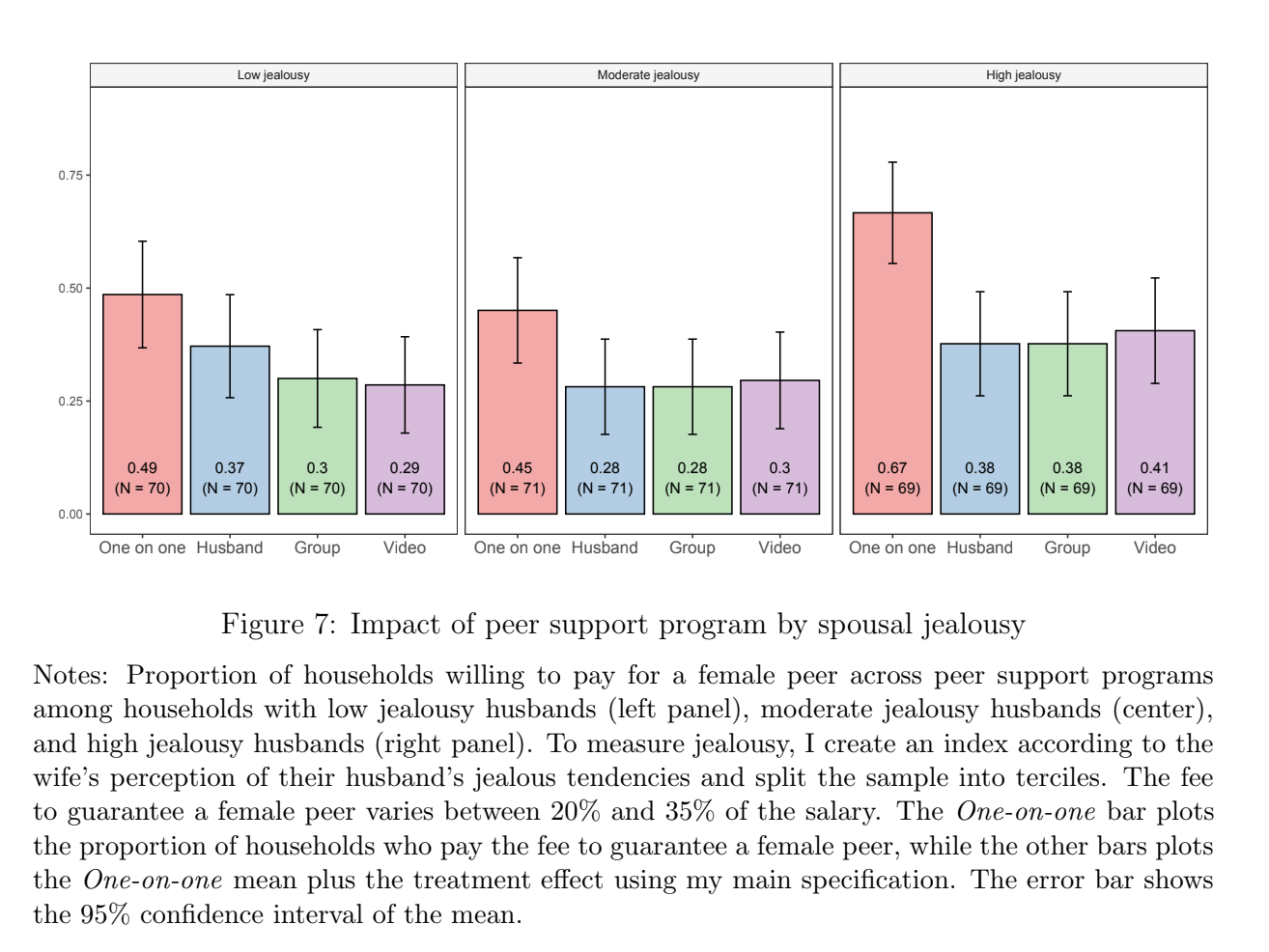

Women were offered a job that included a mandatory online peer support program. They could pay 20–35% of their salary to guarantee that their assigned peer was a woman.

Here’s what happened:

53% paid for the female peer when interactions were one-on-one.

Demand dropped to 34% when husbands could monitor the conversations.

A full 33% still paid to avoid even prerecorded videos featuring a male peer.

This is what Psychologists call a “distaste cost”. In this example, it is the price women pay to avoid triggering jealousy by incurring real financial losses.

How is Jealousy Measured?

The study measures spousal jealousy using a two-question index administered privately to wives. This index includes the following questions:

Direct report: “Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: ‘My husband would be angry or jealous if I were interacting with other men at work?’”

Internalized norms: “Do you agree or disagree with the following statement - Married women should not spend time with men outside their family?”

The index is constructed such that higher values indicate greater spousal jealousy. In the original pre-registered jealousy index, two additional measures were also included:

The fraction of close friends and family who would find it unacceptable for married women to spend time with men outside the family.

“When you leave the house, how often does your husband insist on knowing where you are going?” This measures controlling behavior.

Dimming Their Shine

In conversations with women, I often hear about the pressure to “dim their shine” to keep others comfortable. Rajah’s research provides empirical evidence of this kind of self-censorship. To signal a strictly platonic relationship and avoid triggering suspicion, women with more jealous husbands were significantly more likely to prefer that a hypothetical male colleague address them as “didi” (sister). This small linguistic shift becomes a strategy to manage household dynamics while navigating professional spaces. In other words, women are forced to strip away their name and identity to allows their husbands to feel more secure.

The Bottom Line

This research is a powerful reminder that wages and policies don’t just shape labor markets. They’re shaped by homes, marriages, norms, and emotions, all the messy human parts of economic life that our models often simplify away.

Three takeaways:

Human behavior belongs in our labor equations. Constraints like jealousy operate in the background but have measurable economic consequences.

Policies that expand women-only workspaces may boost labor supply more than wage increases, at least in contexts where household constraints dominate.

New economists are pushing the field forward. Papers like Rajah’s show how the next generation is expanding what counts as “economic behavior.”

If this is the kind of work emerging from the job market, the future of economics is bright and far more human.

Did you enjoy this Decode Econ column? Share today’s post or forward it to a friend. Let’s grow a community that makes economics accessible, one insight at a time.

Very interesting research and findings . It will be worth researching comparing eastern and western cultures . Does husband jealousy appear in both cultures?

Here is a fascinating ChatGPT description of a game theoretic model of (mostly male) spousal jealousy and its effect on partner's behavior. You could set this up as an exercise with students

ChatGPT says: here’s a compact, usable game-theoretic model you can plug into a paper or expand into an empirical test. I give (1) a baseline extensive-form model, (2) closed-form equilibrium conditions, (3) comparative statics and intuition, (4) a few natural extensions (bargaining, stochastic jealousy, enforcement/violence), and (5) testable predictions and policy implications.

Baseline model — sequential extensive form

Players

Wife (W)

Husband (H)

Timing

Nature draws wage offer

𝑤

w to the wife (could be deterministic or random).

Wife chooses labor action

a∈{0,1}: 0 = stay home, 1 = work. If she works she obtains wage 𝑤

w and experiences some benefit 𝐵

B (non-pecuniary: status, consumption).

Husband observes wife’s action and may choose a punishment/response

p∈{0,1}: 0 = no punishment, 1 = punish (punishment represents withdrawal of transfers, increased monitoring, domestic conflict, divorce threat, or costly control). Punishment imposes cost 𝑐𝑊>0

cW>0 on wife and cost 𝑐𝐻>0

cH>0 on husband.

Payoffs realized.

(You can interpret punishment as credible threat if it’s costly for husband but feasible.)

Preferences / payoffs

Wife utility:

𝑈𝑊(𝑎, 𝑝)=𝑎⋅(𝑤+𝐵)−1{𝑝=1}⋅𝑐𝑊−ℓ𝑊UW

(a,p)=a⋅(w+B)−1{p=1}⋅c−ℓW

where ℓ𝑊

ℓW is the non-labor home utility (set to 0 for normalization if she stays home and is not punished).

Husband utility:

𝑈𝐻(𝑎, 𝑝)=𝑌−𝑎⋅𝐽(𝑎)−1{𝑝=1}⋅𝑐𝐻

UH(a,p)=Y−a⋅J(a)−1{p=1}⋅cH

where: 𝑌

Y is baseline household private consumption/utility (independent of wife's labor),

𝐽(𝑎)

J(a) is the husband's jealousy disutility when wife works: set

𝐽(0)=0

J(0)=0, 𝐽(1)=𝛾≥0

J(1)=γ≥0. So if wife works, husband suffers 𝛾

γ (captures jealousy / perceived infidelity risk / loss of status).

Both players discount future costs identically (or consider a single-period model).

Information

Husband observes 𝑎

a before choosing 𝑝

p (sequential with perfect monitoring).

Wife anticipates husband’s response when choosing 𝑎

a.

Strategies

Wife chooses 𝑎

a to maximize expected utility given husband's strategy.

Husband chooses 𝑝

p after observing 𝑎

a.

Subgame Perfect Equilibrium (SPE)

Solve by backward induction.

Husband’s decision after observing 𝑎

a

If 𝑎=0

a=0 (wife stays home):

𝐽(0)=0

J(0)=0 so husband’s payoff if he punishes is 𝑌−0−𝑐𝐻=𝑌−𝑐𝐻

Y−0−cH=Y−cH, and if he does not punish it is 𝑌

Y. So punishing when 𝑎=0

a=0 is dominated (assume no perverse reasons), so choose 𝑝=0

p=0.

If 𝑎=1

a=1 (wife works): husband compares:

No punishment:

𝑈𝐻=𝑌−𝛾

UH=Y−γ.

Punish:

𝑈𝐻=𝑌−𝛾−𝑐𝐻=(𝑌−𝛾)−𝑐𝐻

UH=Y−γ−cH=(Y−γ)−cH.

Because punishment reduces his own payoff by 𝑐𝐻

cH, he will punish only if punishing yields higher utility. Since punishment reduces his own payoff, he never gains by punishing unless punishment changes future behavior (a dynamic deterrence argument). In a single-period model with no future effects, husband never punishes (since 𝑐𝐻>0cH>0). To make punishment credible, we must model dynamic/reputation effects or let punishment impose future benefits (e.g., restores control).

To capture credible punishment: add an immediate private benefit to husband from punishing when wife works — for instance, punishing may reduce wife's outside options or signals dominance, giving husband an immediate small benefit

𝑔>0

g>0. Then husband punishes if:

𝑌−𝛾+𝑔−𝑐𝐻>𝑌−𝛾⟺𝑔>𝑐𝐻.

Y−γ+g−cH>Y−γ⟺g>cH.

So punishment is credible if

𝑔>𝑐𝐻

g>cH.

Wife’s decision anticipating punishment

Wife will work (𝑎=1

a=1) iff:

𝑤+𝐵−Pr(punish ∣𝑎=1)⋅𝑐𝑊>0.

w+B−Pr(punish ∣a=1)⋅cW>0.

Assume husband punishes deterministically when

𝑔>𝑐𝐻

g>cH. Then:

If husband punishes (credible):

𝑤+𝐵−𝑐𝑊>0⇒𝑤>𝑐𝑊−𝐵

w+B−cW>0⇒w>cW−B.

If husband does not punish:

𝑤+𝐵>0⇒𝑤>−𝐵

w+B>0⇒w>−B (trivial if 𝐵≥0

B≥0).

So the jealousy constraint binds when punishment is credible and

𝑐𝑊

cW

large relative to

𝑤+𝐵

w+B.

Equilibrium characterization (simple)

If 𝑔≤𝑐𝐻

g≤cH (punishment not credible): wife works iff

𝑤+𝐵>0

w+B>0.

If 𝑔>𝑐𝐻

g>cH (punishment credible): wife works iff

𝑤+𝐵>𝑐𝑊

w+B>cW.

Thus credible spousal punishment raises the participation wage threshold from

−𝐵

−B to

𝑐𝑊−𝐵

cW−B.

Comparative statics & intuition

Increase in wife’s wage 𝑤

w makes working more likely; higher wages can overcome the jealousy constraint. (∂Pr(work)/∂w > 0)

Increase in punishment cost to the wife

𝑐𝑊

cW makes working less likely.

Increase in husband’s private enforcement cost

𝑐𝐻

cH (or reduction of benefit 𝑔

g) makes punishment less credible → relaxes constraint.

Increase in 𝐵

B (non-pecuniary benefit of work) relaxes constraint.

If wage is stochastic, higher variance (with same mean) can either increase or decrease participation depending on risk preferences.

Welfare

Household welfare under wife working and punishment differs by who bears costs. If punishment reduces total household welfare (i.e.,

𝑐𝑊+𝑐𝐻>0

c+cH>0), then jealousy constraint causes Pareto-inefficient outcomes if wife would have chosen to work absent punishment.

If husband's jealousy has an outside effect (reduces household production), social planner might intervene to reduce

𝑐𝑊

cW (support services) or increase penalties for punishment.

Natural extensions

1) Repeated game / deterrence (credible punishment through future threats)

Model an infinite horizon with discount factor

𝛽

β. Husband can punish today to reduce future probability wife works (or to re-establish an equilibrium with continued punishment). Use trigger strategies: punishment today imposes

𝑐𝑊

cW but deters wife from working in future. Solve for conditions when punishment is subgame perfect (folk theorem flavor). This allows punishment to be credible even if

𝑔<𝑐𝐻

g<cH.

2) Bargaining model (Nash bargaining)

Couple chooses labor and transfers to maximize a weighted sum subject to the threat point (outside options). Jealousy can be introduced as a constraint on the feasible set — e.g., husband’s utility drops by

𝛾

γ if wife’s labor choice has male contact, reducing the joint surplus for those options. A Nash bargaining outcome will pick the option that maximizes weighted surplus. If husband’s threat point (outside option) is strong because wife’s outside option is low, bargaining will favor husband’s preference and limit wife’s labor.

3) Endogenous punishment cost (violence model)

Let

𝑐𝐻

cH be small or zero if husband uses violence cheaply; then punishment is trivial and the wife’s participation threshold is high. Policy levers: increasing husband’s punishment cost via enforcement (legal risk, arrest) reduces credible punishment.

4) Heterogeneous husbands and wives, assortative matching

Model marriage as matching: men with high jealousy parameter

𝛾

γ pair with certain women; selection predicts occupation sorting, lower female labor force participation in high-jealousy matches.

5) Employer behavior

Employers might adjust schedules/locations to accommodate jealous partners (e.g., daytime only). This creates equilibrium occupational segregation.

Testable implications (empirics)

In couples with higher measured husband jealousy (or controlling behavior indicators), wives have lower labor force participation, lower hours, and choose occupations with less male interaction.

Exogenous increases in women’s outside options (e.g., transfer payments, unemployment benefits, legal protection) should raise female labor supply more among high-jealousy households.

Policies that increase the legal/social cost of punishment (domestic violence enforcement, restraining orders, emergency shelters) should increase women’s measured labor participation in affected areas.

Wage shocks (e.g., minimum wage increases) should have smaller effects on participation when credible punishment is present unless the wage increase exceeds the punishment cost

𝑐𝑊

cW.

Simple numeric example (to build intuition)

Take

𝐵=0

B=0. Suppose 𝑐𝑊=5

cW=5. Husband punishes iff

𝑔>𝑐𝐻

g>cH. If punish credible then wife works only if 𝑤>5

w>5. If not credible, wife works if 𝑤>0

w>0. So a wage of 𝑤=3

w=3 induces work when no punishment but not when punishment is credible. This shows how modest punishment costs can block middle-wage opportunities.

Policy levers (how to relax the constraint)

Increase wife’s outside option 𝑤

w or B (training, childcare, subsidies).

Reduce punishment credibility: increase cost

𝑐𝐻

cH (legal penalties, enforcement, social stigma) or reduce husband’s benefit from punishing 𝑔

g (couples counseling to change beliefs).

Reduce the cost to the wife

𝑐𝑊

cW

(shelter, financial transfers, legal protection, divorce aid).

Employer-side accommodation: more female-friendly schedules, same-sex teams, remote work.