Why a Weak Dollar is an Invisible Tax on the Poor

A major economic story this week is the dollar's depreciation. The dollar hit a four-year low. When asked about it, President Trump responded with that is “great”. But, as always, there is more to it. Today’s post is a guest post by Michael Prunka from Enough with Michael Prunka. Let us make sense of how a weaker dollar impacts your pocketbook.

A weakening dollar is often discussed in trading rooms and finance podcasts. But for millions of Americans, it shows up somewhere far more familiar: the grocery store, the gas pump, and the clothing aisle.

For low-income households, currency depreciation is a pay cut they never agreed to.

Families worried about putting food on the table, keeping gas in the car, or buying cleats before baseball season don’t spend much time tracking exchange rates. But they feel the effects all the same.

When the dollar loses value, it acts like an invisible tax—one that falls hardest on households least able to absorb it.

Lower-income families spend a larger share of their income on essentials that are priced in global markets. What Wall Street analysts call a “weaker dollar” shows up in real life as a more expensive bag of rice, a work shirt, or a tank of gas.

Paychecks don’t automatically adjust to dollar depreciation, but prices often do.

The Economics: Why the Dollar Loses Value

At its core, dollar depreciation comes down to supply and demand.

The United States operates under a fiat currency system, meaning the dollar isn’t backed by a physical commodity like gold. Its value depends on how much exists and how much the world wants to hold.

The dollar weakens when:

Supply of dollars increases faster than demand

Interest rates decline, making dollar-denominated assets less attractive to foreign investors.

or any other global event that causes demand for dollars to fall

For decades, the dollar has enjoyed unusually strong demand because of its role as the world’s primary reserve currency. But slower economic growth, elevated inflation, policy uncertainty, and shifts in monetary policy can all chip away at that demand.

When interest rates fall, global investors often move their money elsewhere in search of higher returns. As dollars flow out, the currency weakens.

What’s happening now

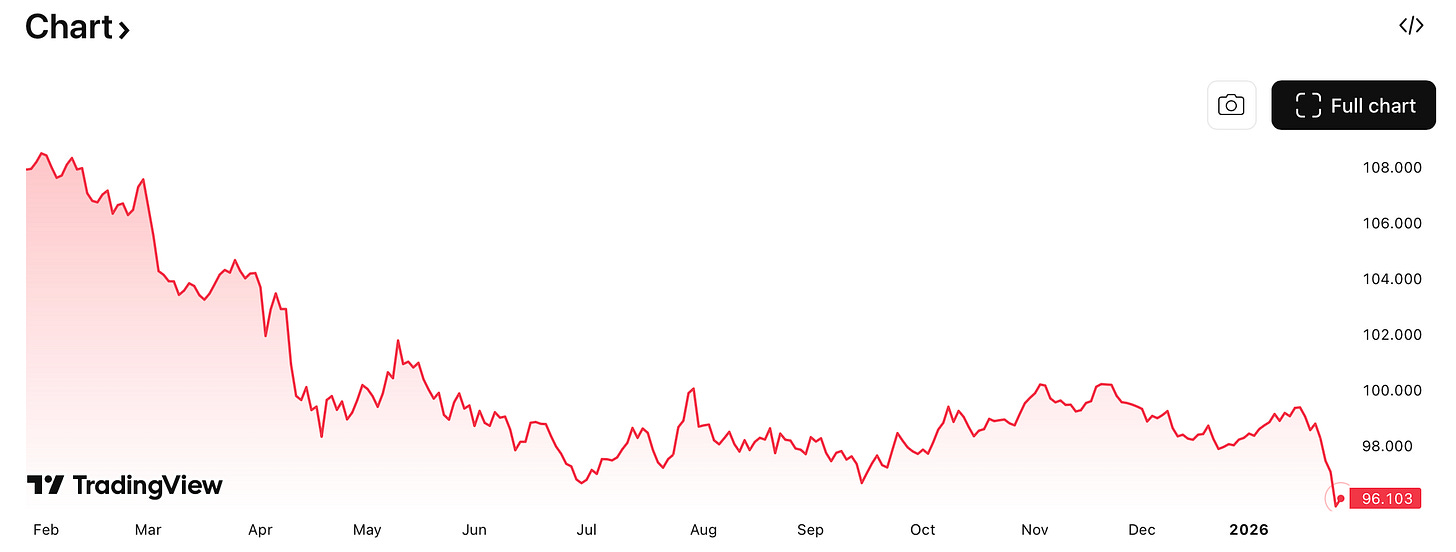

Over the past year, the dollar has declined meaningfully.

The DXY U.S. Dollar Index, which measures the dollar against a basket of major currencies—including the euro, yen, and pound—is down roughly 10.75 percent year over year. The index peaked in early February 2025, dropped sharply in March, and fell again through April amid renewed tariff uncertainty.

Uncertainty surrounding U.S. trade policy and diplomatic relationships, especially with major trading partners that also hold U.S. debt, has added to concerns about further weakening.

The Bottom Line: Who Pays the Price

If the dollar loses value and your wages don’t change, your purchasing power falls. That matters most for households already stretched thin.

The United States remains heavily reliant on imports. Clothing, electronics, coffee, oil, and out-of-season produce are all priced in global markets. When the dollar weakens, it takes more of them to buy the same goods.

Lower-income households already spend a disproportionate share of their income on groceries and utilities. They have little room to adjust. Wages at the bottom of the income distribution also tend to be sticky, slow to rise even when prices do.

Wealthier households are more likely to own stocks, real estate, or other assets that rise with inflation and offer some protection against inflation. Poorer households usually have only their labor, and wages rise slowly.

A weaker dollar can make U.S. exports more competitive and support some jobs. But those benefits arrive unevenly and often lag behind rising living costs. Rent, food, and fuel get more expensive long before relief shows up in paychecks.

Beyond the Charts

Dollar depreciation may sound like a technical issue best left to economists and traders. In reality, it’s a kitchen-table problem.

A weak dollar doesn’t just show up on financial charts—it shows up in tighter grocery budgets, harder trade-offs, and fewer options for families already doing their best to get by.

Understanding currency values helps us understand affordability. And affordability—especially for the most vulnerable households—is shaping economic and political debates heading into this year’s midterm elections.

– Michael Prunka

About The Author

Michael Prunka holds degrees in economics and journalism from East Carolina University. His publication, Enough with Michael Prunka , explores hunger and food insecurity through an economic lens. Subscribe to Enough if you believe no one in America should have to wonder how they’ll feed their family.

I'm not a macroeconomist, so I historically avoid most conversations like this. I appreciate how simple you made this.

We shouldn't ignore the growth rate of US National Debt as a function of lower dollar valuation. With the current Administration's policies on tariffs and the "Mad Man Theory" dominating trade negotiations, Treasuries need a risk premium to attract investment. (Another thing they miss about Foreign Direct Investment. Reputational harm eventually creates markets for investment any other place.)

*I've stared at this post wondering about Subsitution Effect and the assumption about the Wealth Effect influencing spending. You may want to look into how RMDs are creating increased spending among retirees.