AI May Already Be Displacing Workers

What does this mean for monetary policy and the Fed?

In a recent post, Dr. Abdullah Al Bahrani and Dr. Jeni Al Bahrani observe that young, college-educated men (ages 23-30) are experiencing an unemployment rate higher than that of those with only a high school diploma. This is unusual, to say the least, and they mused whether this could be a canary in the coal mine for how our current higher education system prepares graduates for a quickly changing workforce.

The Canary in the Coal Mine

Indeed, a new paper claims exactly the same thing. Researchers from Stanford’s Digital Economy Lab used ADP1 data for millions of workers and found evidence that AI may already be displacing workers seeking entry-level jobs. The full paper is worth reading and identifies six takeaways, but what stands out most is the authors find:

…substantial declines in employment for early-career workers (ages 22-25) in occupations most exposed to AI…

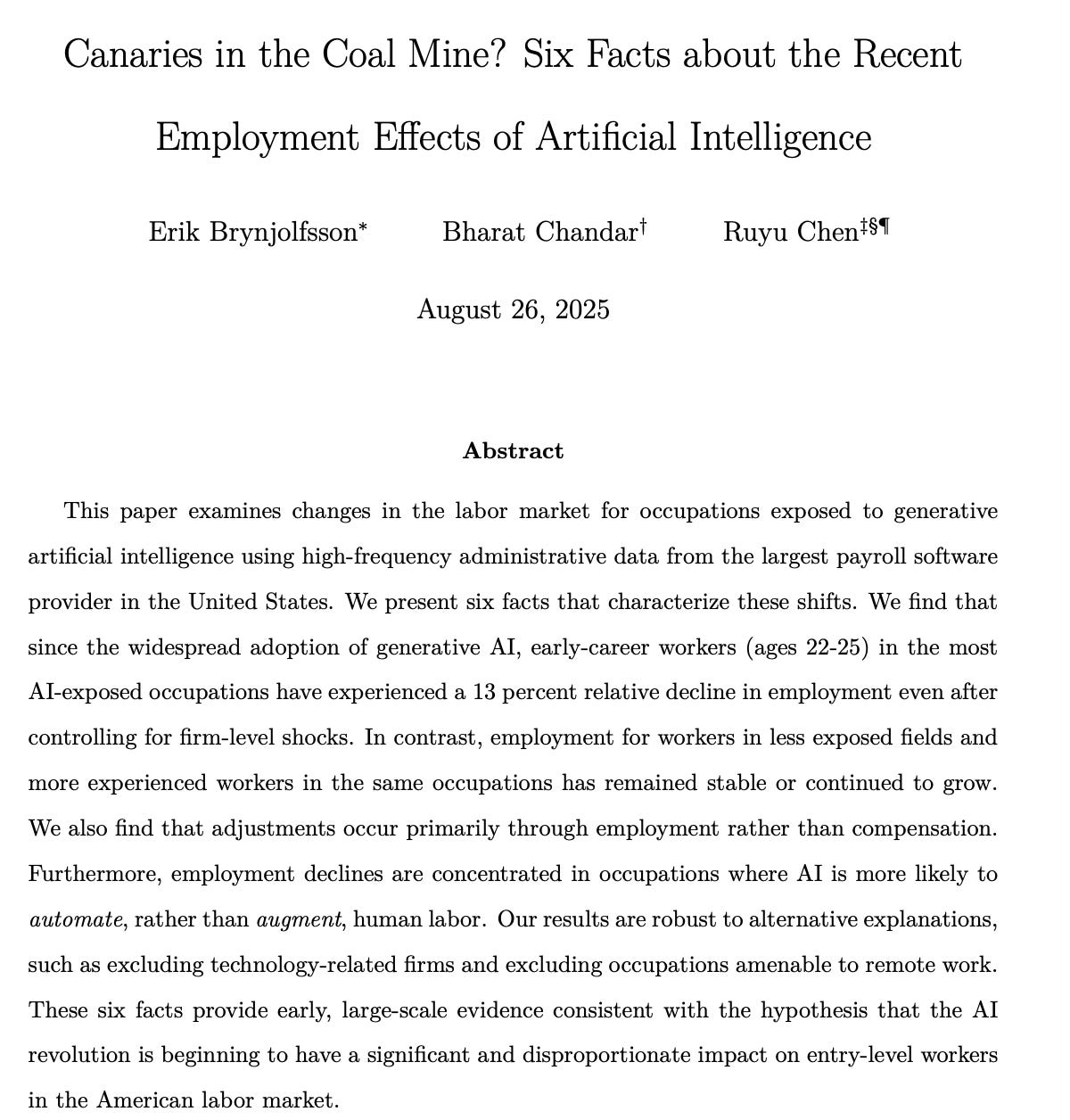

A couple of striking graphics from the paper help tell the story. The first graph shows growth in the number of young workers (ages 22-25). The graph is normalized to coincide with the release of ChatGPT (the vertical solid line in the middle of the graph). This means that everything above 1.0 in the graph represents growth in the labor market for these people, while everything below 1.0 means the labor force for this group is shrinking. Notice the darker line, which shows that workers in the sector most exposed to AI experience a decline in total workers, while those in the least-exposed fields (lighter gray) continue to grow on a similar trajectory as before ChatGPT.

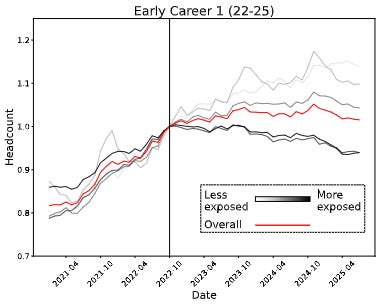

In the graphs below, you can see that the gap between the lines progressively narrows for workers ages 26-30 and even more so for workers ages 35-40. The authors have many more graphs that show the gap disappears almost entirely as you continue to move up the age range of workers. These patterns suggest that AI may be substituting for workers who lack work experience and are performing jobs that are easily automated.

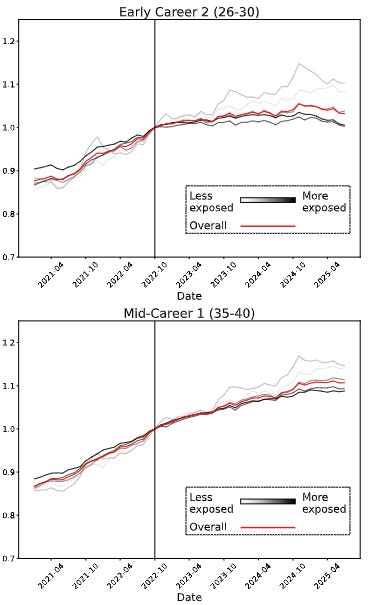

Data from official government sources are also consistent with this story. One striking graph comes from the New York Federal Reserve Bank (h/t to Brian Lynch for the suggestion). This shows that the unemployment rate for recent college graduates (light blue) is now higher than the unemployment rate for the whole population (dark line). Notice the gap has widened since 2022.

What Does this Mean for Monetary Policy?

In the near term, probably nothing. However, if a new generation of workers finds it harder to find their initial jobs, then that slows their career earnings potential. In turn, this may be a drag on future economic growth, as these individuals reach other milestones later, such as buying a house.

A potentially larger issue for monetary policymakers is that lowering interest rates may not provide the same market response in the future. Traditionally, stimulating the economy meant lowering interest rates to incentivize firms to borrow and spend, hiring workers in the process. This helped lower the unemployment rate and increase economic growth, among other benefits. However, if companies are more likely to employ some form of AI instead of new workers, then that limits the effectiveness of the Fed’s preferred policy lever. This poses a challenge for a Fed that seeks to balance low, stable prices with maximum employment.

What Does This Mean for the Value of Higher Education?

Now, more than ever, it is vital that our higher education system emphasizes experiential learning. In other words, students need practice doing authentic assignments and working with real companies and community partners. “Book smarts” is simply not sufficient in today’s world. Many professors may need to redesign their courses to teach students how to complement new AI technologies.

The Econ Games: A Model for Experiential Learning

One way to bridge the gap between the classroom and the workforce is through programs like The Econ Games. Each year, students from universities across the country team up to solve real business problems using data provided by corporate and nonprofit partners. The experience provides students with technical practice, helping them develop teamwork, problem-solving, and communication skills that employers seek. Most importantly, it provides students with an opportunity to apply economic thinking in a setting that mirrors the challenges of today’s labor market.

As Patel, Al-Bahrani, and Hoyt (2024) demonstrate in The American Economist, the competition has evolved into an annual event with participation from over twenty institutions, offering students authentic practice, professional networks, and career opportunities. By embedding more opportunities like this into higher education, we can better prepare graduates for a world where adaptability and human-centered skills matter as much as technical knowledge.

The Bottom Line

The labor market is shifting rapidly in real-time. Past transitions, such as from agriculture to manufacturing and manufacturing to services, took decades. As technology takes on a larger share of production, securing a foothold in income-earning opportunities is becoming increasingly difficult. This is especially true for young, college-educated workers. We’ve highlighted the need for human-centric skills in education, but the bigger question remains: can our policies and social programs evolve fast enough to meet this challenge?

About the Author:

Brandon J. Sheridan is an Associate Professor of Economics at Elon University's Martha and Spencer Love School of Business. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics (2012) and an M.S. in Economics (2009) from the University of Kentucky, and a B.S. in Economics and Government (2006) from Centre College.

Please subscribe to his newsletter to access more of his articles.

ADP is a private firm that specializes in, among other things, processing payroll for companies. This gives them access to data on employment for millions of workers. They produce a monthly employment report based on this (anonymized) information that they share with the public to help gauge the health of the labor market.

Brynjolfsson is a very good economist, and yet I have found he is inclined to exaggerate the effects of AI. Here is an article from the BLS from 2022, which looks IMHO excellent, demonstrating that some jobs that had been selected as likely targets for shrinking by AI, nevertheless grew as a result of factors the economists did not take into account. I remember all the hooplah about MOOCs a number of years ago, which proclaimed that teaching was a vanishing profession -- which turned out not to be true. Mr Trump's disruption of the BLS will have incalculably large effects on the production of great economics papers by people who do not splash their famous names across papers, but somehow produce excellent work. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2022/article/growth-trends-for-selected-occupations-considered-at-risk-from-automation.htm

I'll pressure you the same way that I did the Dr. As. The unemployment rate for recent college grads went above the unemployment rate for all workers *before* the pandemic, which was before widespread knowledge of LLMs and AI agents.

I'm not dismissing that AI has had an outsized influence in the past few years, but what trends might we be overlooking from before 2022?