The Corporate Catfish Experiment

How one viral LinkedIn experiment revealed bias in hiring

Yesterday, I gave a workshop to our students on leveraging LinkedIn for career advancement. One of the discussion points that arose was about profile pictures and their importance. In my post-workshop reflection, I couldn’t help but think of Aliyah Jones’s experience and my neglect to share some of the downsides of the job search process. Today, I am sharing Aliyah’s job search experience with you, along with some of the research that provides evidence to support her personal story.

When Aliyah Jones couldn’t land a job despite strong qualifications, she decided to test whether bias was holding her back. She created a LinkedIn profile for a fictional woman named “Emily” with identical credentials to hers; the only difference was that Emily was White. The results of the experiment will surprise you.

Over eight months, Emily’s profile outperformed Jones’s in every metric. Recruiters engaged more, ghosted less, and extended interview invitations nearly six times more often.

Jones documented her findings in a viral TikTok docuseries, Corporate Catfish, which she is now expanding into a full-length documentary: Being Black in Corporate America.

What the Numbers Show

Interview invites: Emily 57.9% vs. Jones 8.9%.

Recruiter engagement: Recruiters were more likely to engage with Emily by sending emails, while Jones’s inbox stayed empty.

Ghosting: When both candidates engaged with recruiters, Jones’s interactions were twice as likely to end with the recruiter ghosting her.

While the LinkedIn profiles were identical, and recruiters were engaging with the same person, the outcomes were drastically different.

Decades of Evidence

While Jones’s story is personal, what she experienced has been documented in the research. Her results align closely with some academic papers that I often recommend:

Bertrand & Mullainathan (2004)1: They conducted the same experiment but used traditional resumes. The resumes were identical, with the minor twist that some had “White-sounding” names and others had “Black-sounding” names. The result is that “White-sounding” names received 50% more callbacks than “Black-sounding” names.

Ge & Wu (2021)2: Economics Ph.D. candidates with harder-to-pronounce names were 10% less likely to secure tenure-track jobs.

Daniel Hamermesh3: finds that physical attractiveness significantly affects earnings, with attractive workers earning a “beauty premium” of about 5%. In comparison, less attractive workers face an “ugliness penalty” of up to 10%, even after controlling for education and experience.

Hamilton, Goldsmith & Darity (2007)4: Among African Americans, lighter-skinned individuals earn higher wages than darker-skinned peers, even after controlling for education and experience.

Hamilton, Goldsmith & Darity (2009)5: Lighter-skinned Black women are more likely to marry than their darker-skinned counterparts, holding other factors constant.

There is extensive research providing evidence of bias in labor markets, resulting in disparities in social outcomes. What Jones added was visibility. She transformed data into lived experiences, capturing, documenting, and sharing them with millions.

Why Bias Persists

Economic theory suggests that discrimination should disappear as efficient firms attract overlooked talent. Reality tells a different story; our current markets are allowing discrimination to persist.

Three forces explain why:

Information blindness – Many firms fail to recognize or acknowledge their own biases. Additionally, it is challenging to identify which firms are engaging in discriminatory behavior, thereby allowing bad practices to persist and good candidates to be overlooked.

Network reinforcement – Homogeneous hiring practices replicate themselves through referrals and a “culture fit.” How we hire hides bias by calling it by a different name. “Preferred schools” is one that I come across when companies recruit from universities. It sends the signal that some schools have students who are a better “culture fit” than others.

Technology acceleration – AI amplifies bias faster than competition can correct it. Automated processes and AI screening can reinforce previously bad practices through systems that have been trained on biased processes.

The Bottom Line

Jones’s new documentary will expand the story beyond LinkedIn, exploring the daily realities of Black professionals navigating bias in workplaces across the nation.

Her experiment may have started as an act of personal frustration. Her story stands as evidence of how discrimination distorts labor markets, at a cost measured not just in lost opportunities, but in billions of dollars of wasted economic potential.

What I love about Jones’s approach is that she saw a problem in this world and invested in trying to solve it. In doing so, I hope she will create new opportunities for herself and, in turn, open doors for others. She has shown resilience and persistence.

Whether we like to admit it or not, the hiring process is susceptible to discriminatory behaviors. Free markets require information to be accessible; talking about the problem is one way of allowing labor markets to improve. We can’t solve a problem that we do not acknowledge.

Reader Question: Have you experienced hiring bias in your industry? Reply and share your story. Your experiences help uncover broader economic patterns.

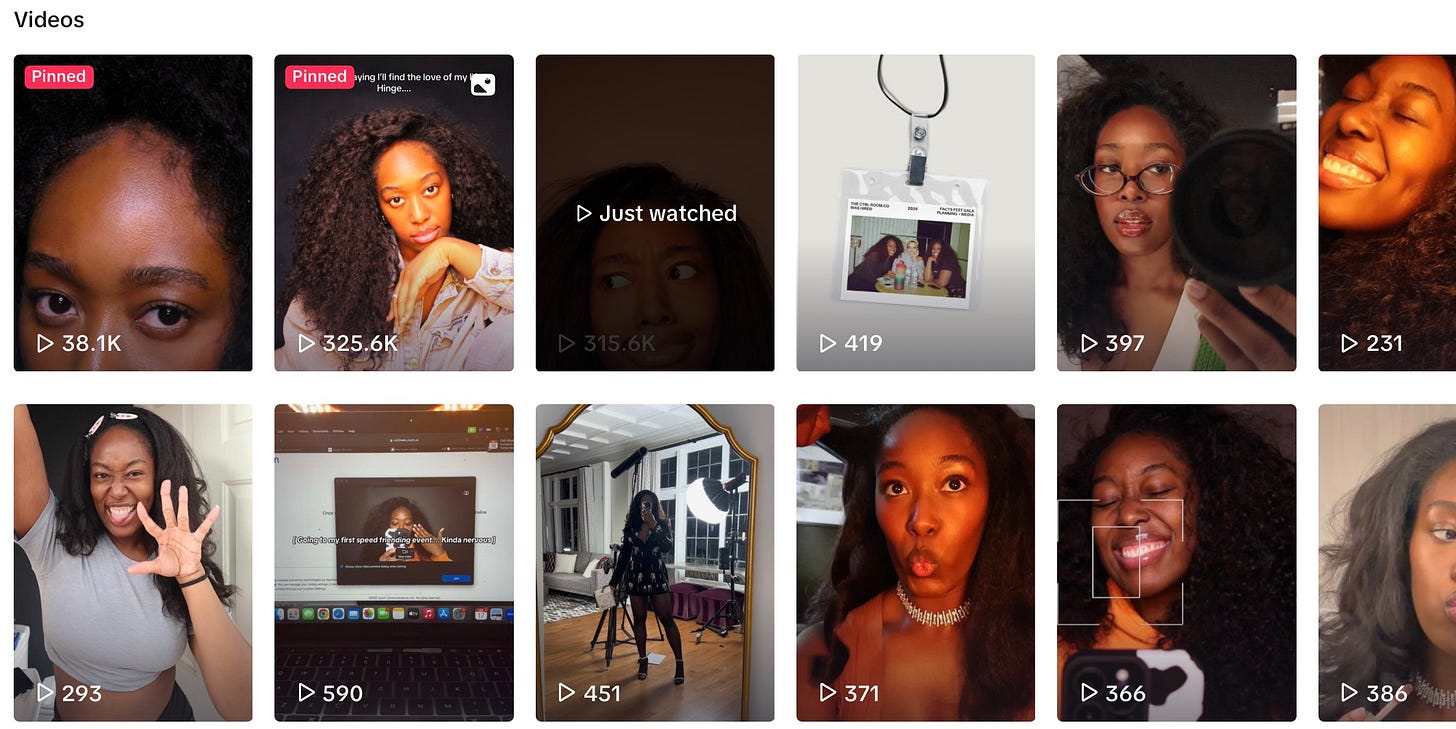

Jones’s TikTok Account

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991-1013.

Ge, Q., & Wu, S. (2024). How do you say your name? Difficult-to-pronounce names and labor market outcomes. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 16(4), 254-279.

Hamermesh, D. S. (2011). Beauty pays: Why attractive people are more successful.

Goldsmith, A. H., Hamilton, D., & Darity, W. (2007). From dark to light: Skin color and wages among African-Americans. Journal of Human Resources, 42(4), 701-738.

Hamilton, D., Goldsmith, A. H., & Darity Jr, W. (2009). Shedding “light” on marriage: The influence of skin shade on marriage for black females. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 72(1), 30-50.

The solution to the name/ethnicity bias in hiring is simpler than most consider. Simply voiding the field when the information is accessed by a potential employer/recuiter works best. For years my former employer required that HR not share that information so that merit based hiring could be the standard and not something that needed awareness. (This argument does collapse when an individual may have attended an HBCU or a program geared towards a "special ability".)

Maybe due to being on the Behavioral side of Econ I'm more cognizant of implied baises and the methodology to address those same biases, but that also falls on employers/education providers to develop internal systems than address individuals and not whatever upload LinkedIn provides.

This is a complicated area of inquiry, and will continue to receive serious attention. If this became tangled up in a legal squirmish, we'd all benefit from learning the causal effect of race on job choice. Here is more recent research in the area, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104079