The Metal Ceiling: Silver Is Becoming AI’s Bottleneck

This is a guest post by Decode Econ Educator Network member Dr. Cecilia Cuellar, Economist and Research Analyst at the Hibbs Institute for Business and Economic Research at the University of Texas at Tyler.

The digital economy’s best trick was making itself feel weightless. We called it “the cloud,” as if computation hovered somewhere above factories, mines, and power plants. For a while, that story held. Software scaled. Storage got cheaper. The internet felt like a place you could copy and paste into existence.

Then AI arrived and exposed the hidden floor. Not because AI is less digital, but because it is more demanding. It turns computation into a high-intensity industrial process: more heat to manage, more power to move, tighter tolerances, and denser hardware. At that scale, growth stops being limited by ideas and starts being limited by the physical inputs that keep machines stable.

That is where silver keeps resurfacing. Not as a headline, but as the quiet constraint behind high-performance computing. If AI is the story we see, silver is the ghost in the machine that helps make it run.

This is a story about Silver.

The moment the market started telling a different story

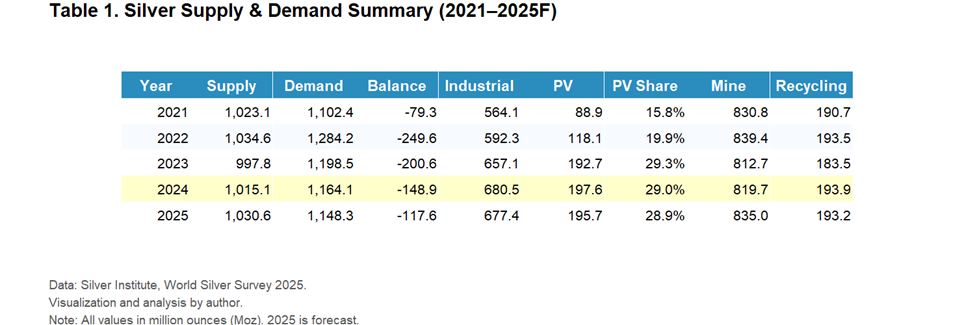

Markets are practical. When something becomes structural, they record it in quantities. In 2024, global silver demand was about 1.16 billion ounces, industrial demand reached a record 680.5 million ounces, and the market ran a deficit of about 148.9 million ounces.1 A deficit means the world used more silver than it produced, so the gap had to be met from metal already above ground, inventories, stockpiles, and whatever could return through recycling or resale. In plain terms, part of today’s demand was met by drawing down yesterday’s supply.

Figure 1 shows when this becomes the new normal. Around 2021, the market shifted from occasional surpluses to repeated deficits. Once that pattern holds, the question stops being “what is the price of silver?” and becomes “where does the metal go first?” That is the metal ceiling, a persistent allocation problem rather than a one-time shortage.

Inside the machine: inelastic demand

Silver demand becomes inelastic in AI for the same reason seatbelts are not optional in a car. Inelastic demand means buyers continue to purchase even as prices rise because there is no acceptable substitute. When a system is built around a minimum performance requirement, you do not switch away from the component that keeps it safe and functional.

AI infrastructure pushes silver into that category. In a normal purchase, you can trade quality for price and live with the compromise. In a data center, the compromise shows up as heat, signal noise, and failures that interrupt service. That is why silver matters. Silver sits in the pathways where power and signals have to move cleanly.2 If you replace it with a weaker alternative, you are not just saving money. You are taking on more downtime risk and a lower performance ceiling. When the cost of failure is that high, buying decisions stop looking like shopping and start looking like reliability management.

Outside the machine: the energy loop

This is the missing piece of the puzzle. People hear that AI needs a lot of power, but the real constraint lies in how we plan to supply it.

The International Energy Agency projects that electricity use from data centers roughly doubles to about 945 terawatt-hours per year by 2030,3 which is slightly more than Japan’s total electricity use in 2024.4 Meeting that demand requires building new generation. The same agency projects almost 4,600 gigawatts of additional renewable power capacity between 2025 and 2030 and finds that solar panels account for nearly 80% of that expansion.³

That is the loop that brings silver back to the center. Solar panels are among the largest industrial uses of silver, so the push to power AI with solar increases electricity demand and, in turn, silver demand.

Figure 2 shows the same pattern in the demand data. Photovoltaics demand rises to roughly a third of industrial silver demand and remains elevated.

In the ground: why supply cannot sprint

Higher prices usually bring more supply. With silver, the supply response is slower.

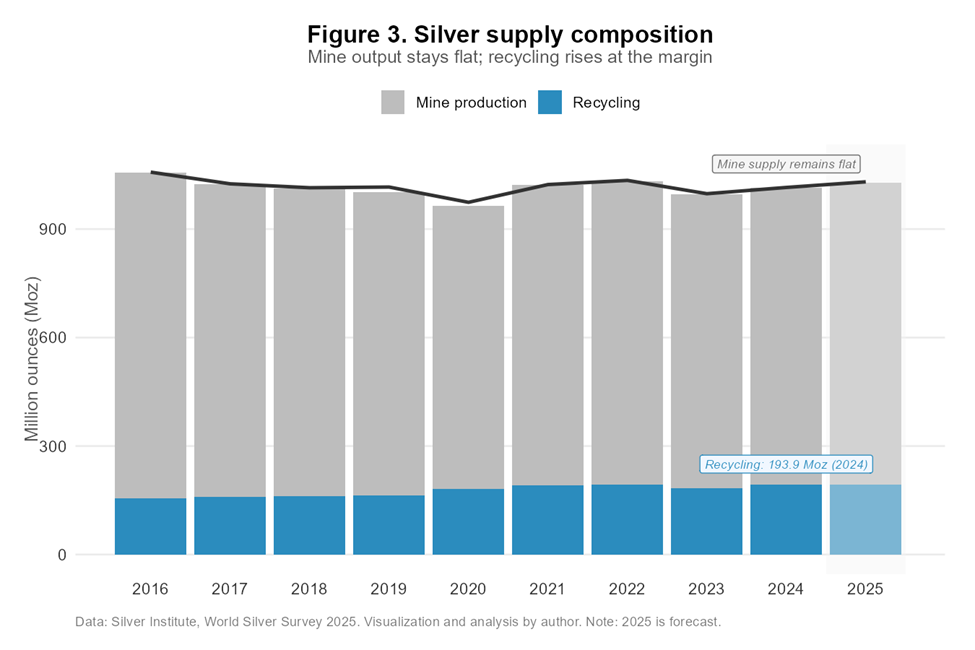

Figure 3 makes the constraint clear. Total supply is relatively flat. Recycling increases, but only modestly. Mine output does not surge when demand strengthens, so the market adjusts through small, incremental shifts rather than a rapid supply response.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates global silver mine production at around 25,000 metric tons in 2024, about 2% lower than in 2023.5 A key reason supply is slow to respond is that much of silver output is produced as a byproduct of mining other metals. In many cases, companies expand production of copper, lead, zinc, or gold first, and silver comes along for the ride. As a result, silver supply cannot ramp up quickly just because silver demand rises.

The Bottom Line

When people say, “AI is eating the world,” they usually mean scale without friction. In practice, AI is teaching a different lesson. Scale has a price, and the price is physical.

Table 1 shows the constraint in one place. Demand has outpaced supply for several years; deficits persist, and industrial uses continue to pull, especially electronics and solar. When that pattern holds, silver becomes an allocation problem. The question is not only what silver costs, but where the ounces go first.

Why should you care? When a key input becomes a bottleneck, costs do not stay within tech companies. They may pass through. Into the price of electrification and electronics, into the cost of building and connecting new power, and into the financing of data centers that show up in your utility territory. Over time, that pressure can surface as higher utility rates, higher costs for solar and grid upgrades, and higher prices for the devices and components that rely on the same supply chains.

Seen this way, ‘silver standard’ is not a metaphor for prestige. It is a shorthand for a system that increasingly has to organize around a hard, physical constraint. The cloud still exists. It just has a floor now. And that floor is made of metal.

About The Author

Cecilia Cuellar is an economist at the Hibbs Institute for Business and Economic Research at The University of Texas at Tyler, where she supports regional economic development by translating data into practical insights for communities and decision-makers in East Texas. Her research agenda focuses on understanding how AI may reshape local labor markets and regional economic development outcomes. Follow her on Substack for data-driven stories that connect economic ideas to real-world decisions, and connect with her on LinkedIn.

The Silver Institute (2025). Silver Supply and Demand. https://silverinstitute.org/silver-supply-demand/

Sancheti, A. (January 24, 2026). Silver Demand in 2026: Technology, Industry, and the Future of Global Markets. Uniathena. https://uniathena.com/silver-market-demand-trends

IEA (2025), Renewables 2025, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2025, License: CC BY 4.0

Our World in Data (2026). Energy: Japan Profile. Primary Energy Consumption. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/primary-energy-cons?tab=line&country=~JPN

U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2025. https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025-silver.pdf

I have often wondered how much of Innovation is constrained by physical materials. Semi conductors can only get so small. There is only so much silver. Etc. This is a good example of that. It will be interesting to see if an alternative can be developed or if certain sciences are finally hitting metal ceilings.

Great paper and extremely relevant with the increase in silver prices being a hot topic of discussion. At what point do material constraints seriously limit the growth of AI?