What Do We Really Expect From College Professors?

A conversation with my friends and a question for my students

This post was inspired by a conversation I recently had with educators who continually energize me. These are faculty who have devoted their lives to improving their students' lives by asking a simple yet profound question: What do students actually need?

I teach economics. I oversee graduate programs. And the longer I do this work, the clearer one thing becomes: People have a lot of expectations of faculty, and those expectations don’t always match.

Some want us to focus on content.

Some want skills.

Some want job preparation.

Some want citizenship preparation.

Some want critical thinking, and others want none of the political noise that comes with it.

It is a confusing time for education, and these questions are a sign of an education system caught between what it was and what the world now needs it to be.

Today, I want to talk about the power of faculty and what students need.

The Problem: Students Are Struggling, Employers Are Worried, and Confidence in Higher Ed Is Falling

Let’s start with the reality inside classrooms today.

Gen Z is entering college with the poorest mental health of any generation on record.

Jonathan Haidt’s research shows rising numbers of students, both men and women, believe:

“People like me don’t have much chance at a successful life.”

Students aren’t just stressed when they arrive; they have lost hope and confidence. The economic system is shifting, and many feel unprepared to navigate it.

At the same time, employers are sounding alarms.

A recent AAC&U survey found that only 60% of employers believe graduates have the skills for entry-level jobs. Nearly 73% say graduates lack essential soft skills, or transferable skills as Dr. Jeni Al Bahrani calls them :

communication

critical thinking

teamwork

adaptability

A separate study found 75% of companies are disappointed in their recent hires, despite their strong academic performance. Employers describe young hires as unprepared for professional norms:

50% unmotivated

46% poor communicators

39% lacking professionalism

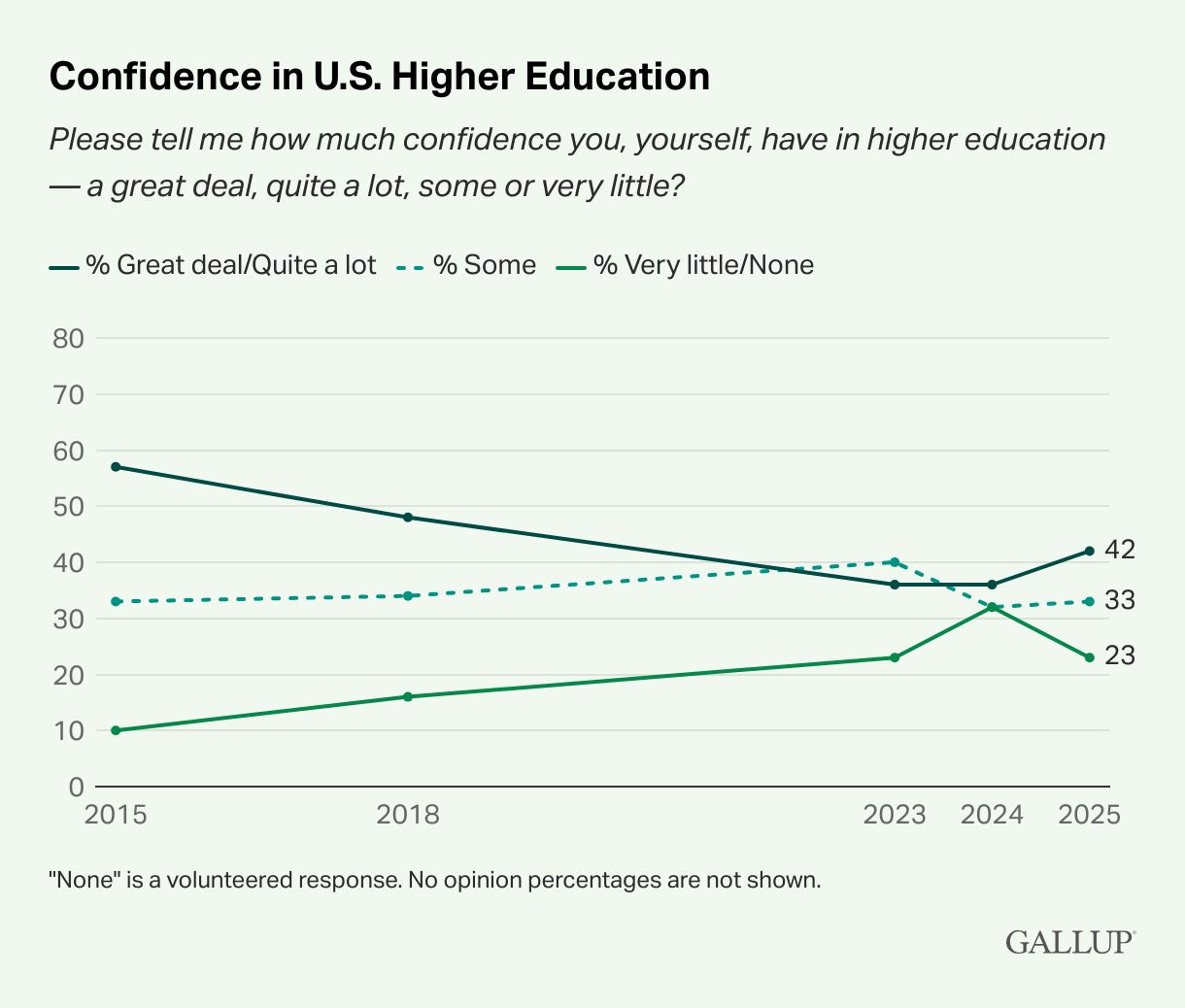

And public trust in higher education has dropped from 57% to 42% since 2015.

Yet, the response from higher education has been slow, at best. Some are still clinging to the old models in a world that has moved on.

The Economics: What People Now Expect From Faculty

Most people think professors are content experts, which they are. However, their role in the classroom requires more of them. In reality? That’s the least important part of the job today.

1. Faculty as Curators of Learning

Information has never been as readily available to our students as it is today. Where they need help is in making sense of the information and connecting the dots.

Students need help:

filtering information

evaluating sources

forming sound judgments

navigating uncertainty

In an age of misinformation, this is economic value creation.

2. Faculty as Community Builders

In my paper, “Classroom Management and Student Interaction Interventions: Fostering Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging in the Undergraduate Economics Classroom,” I share that when faculty intentionally design classrooms around belonging, interaction, and inclusion:

engagement rises

learning improves

students feel more connected

confidence increases

The takeaway: Students learn best in classrooms that feel like communities, not content warehouses.

In a generation struggling with isolation and anxiety, the professor’s ability to build belonging is not “extra.” It is a core learning outcome. Faculty are often focused on the content that they need to cover, but my question is how are you investing in your classroom community?

I have found that “connections before content” is a great way to set my intentions in the classroom, both in virtual and in-person settings.

3. Faculty as Human Capital Developers

Employers consistently tell us the missing skills are:

communication

problem-solving

teamwork

project management

adaptability

professionalism

These are skills built through practice, interaction, and mentorship, not lectures alone.

The labor market is shifting toward skills-based hiring, and many companies are even dropping degree requirements. Higher education must adapt or risk irrelevance.

4. Faculty as Mentors and Stability Anchors

Students come to us overwhelmed, anxious, and unsure. Sometimes we are the first adult in their lives to say, “You can do hard things. Let’s work through this.”

This mentorship is not emotional labor; it’s skill-building. Students who learn resilience, communication, and professionalism succeed long after the final exam. I see this growth every year with students who participate in the Research Fellows program and the Econ Games. The mentorship program helps them build resilience, handle ambiguity, manage stress and expectations, and develop a sense of self-worth through their accomplishments.

5. Faculty as Translators of Relevance

Our students want to know:

Why does this matter?

How does this help me get a job?

How does this help me build a life?

When faculty connect academic ideas to economic realities, learning becomes meaningful. How are you bringing content to life? Education should be experiential, not passive. Good faculty engage, great faculty inspire.

So What Should a College Degree Deliver?

When you put all the data together, four expectations rise to the top:

1. Cognitive Skills

Graduates should be able to:

think critically

analyze data

write and communicate

solve problems

These are the foundations of long-term economic mobility.

2. Transferable, Work-Ready Skills

The skills employers keep asking for:

teamwork

communication

project management

ethical reasoning

adaptability

These are learned through interaction.

3. Identity, Confidence & Professional Maturity

College helps students develop:

resilience

habits

networks

belonging

purpose

This is where faculty make the biggest difference.

4. Mobility, Opportunity & Economic Stability

A degree should still be an engine of upward mobility.

But that promise only holds if higher education stays relevant and responsive.

The Bottom Line

People expect more from professors today because students need more, and the world demands more.

Faculty are not content providers, they are community developers, mentors, traslators of relevance, and architects of belonging.

This is the real work of higher education. This is the work that changes lives.

And if we embrace it, education remains one of the most powerful forces for economic and social mobility we have.

Your students need you.

What do you think the role of a professor is? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Great piece. There is also a role for universities to empower their faculty to better serve their students. In large classes, it’s hard to engage students while also finding time to provide individualized feedback. Some faculty are also expected to produce research and serve on committees which are equally demanded jobs.

1. I love what you are saying, Jeni. 2. Linda's points are absolutely valid, of course, and critical to the long-term success of higher ed in the US -- and are mostly ignored by 4-year institutions, especially those that are research-oriented, such as my alma mater, Harvard University. It may be that elite 4-year institutions are not as subject to failure by virtue of poor teaching, regardless of research success -- Gen Z will be the test of that. 3. I work at a community college, and we live or die by good teaching. You may note that community colleges saw an increase of 4.0% in Fall enrollment in 2025; 4-year public institutions nationwide saw a 1.9% increase; private 4-years 0.9%, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Yes, this is partly because of more students realizing that some form of higher ed is needed to get a good job. That said, 80% of CC students intend to get a 4-year degree. Only 16% nationwide ultimately do so, although 40% transfer, because of money, work and other life issues, problems transferring credits, struggles when they do transfer, etc. Do 4-years focus on the success of CC transfer students, or are they stigmatized, or ignored as a group? I recently went to a nationwide convention of Caring Campus, a group that promotes college efforts to improve student feelings of belonging -- only ONE attendee was a 4-year institution -- University of Texas Lakeside -- all others were community colleges, which are working powerfully in exactly the areas you cite, and which are supporting faculty efforts by increasingly incentivizing teaching success and overall student success. By the way, in Texas the legislature has switched its funding model for CCs to one which is based on graduation rates of students.