The Hidden Tradeoffs Behind Today’s Biggest Social Trends

What Shonda Rhimes, fertility rates, and television teach us about tradeoffs

Today, we are discussing why saying yes to one thing always means saying no to something else.

I’m currently listening to The Year of Yes by Shonda Rhimes, and one theme keeps sticking with me. As her career took off, she felt that she was failing elsewhere, especially as a mother. When work was thriving, home felt neglected. When she tried to reclaim family time, professional momentum slowed. She continuously felt like she was failing.

What Rhimes makes painfully clear is something many of us experience but rarely say out loud: time is finite. Saying “yes” in one part of life almost always means saying “no” somewhere else. That tension isn’t a personal failure. It’s a constraint, and we all face it.

Economists have a name for this: tradeoffs. Seeing the world through this lens is powerful because it forces us to confront reality rather than guilt. When you recognize that every choice has an opportunity cost, decisions become clearer, even when they remain hard.

More importantly, this way of thinking scales. It doesn’t just help individuals make better choices; it helps societies design better policies by asking a simple but uncomfortable question: what are we giving up, and who bears the cost?

The Economics

At its core, economics starts with a simple idea: resources are limited, and our wants are unlimited. We must make choices, and those choices have consequences. Time is one of the most binding constraints we face. You can’t add hours to the day. You can only reallocate them. But this logic doesn’t apply to time alone. It governs all resources, from money and attention to labor and public budgets. Every allocation is a tradeoff.

Individually, those choices feel personal. Collectively, they become social outcomes.

Take Fertility

Across much of the world, fertility rates are falling. They are often presented as shifts in preferences or culture, but those changes stem from economic factors. It’s about time, incentives, and opportunity costs. As housing, childcare, healthcare, and education costs rise, more households need two incomes to stay afloat. More hours in paid work mean fewer hours available for unpaid work at home, including raising children.

This is where economists get uncomfortable, but honest. We don’t moralize the outcome. We ask what tradeoffs people are responding to.

The Power of TV and Its Impact on Women

A striking example comes from India. Researchers Robert Jensen and Emily Oster studied rural villages across five Indian states. When cable television became available, fertility declined within a year. Similar patterns were documented in Brazil by Eliana La Ferrara, Alberto Chong, and Suzanne Duryea.

What’s doing the work here isn’t television itself; it’s the tradeoffs television reveals.

Why would TV affect birth rates?

Cable TV didn’t mandate fewer children or more education. It expanded the set of visible life paths and altered how women allocated their time and aspirations. Women saw other women live different lives. Exposure to new norms raised the perceived returns to education, autonomy, and delayed childbearing. With finite hours in the day, investing more time in schooling, paid work, or personal agency increased the opportunity cost of early and frequent births.

Fertility didn’t fall because preferences disappeared. It fell because the tradeoffs became clearer. The more you learn about the tradeoffs of your actions, the more confident you feel about your decisions.

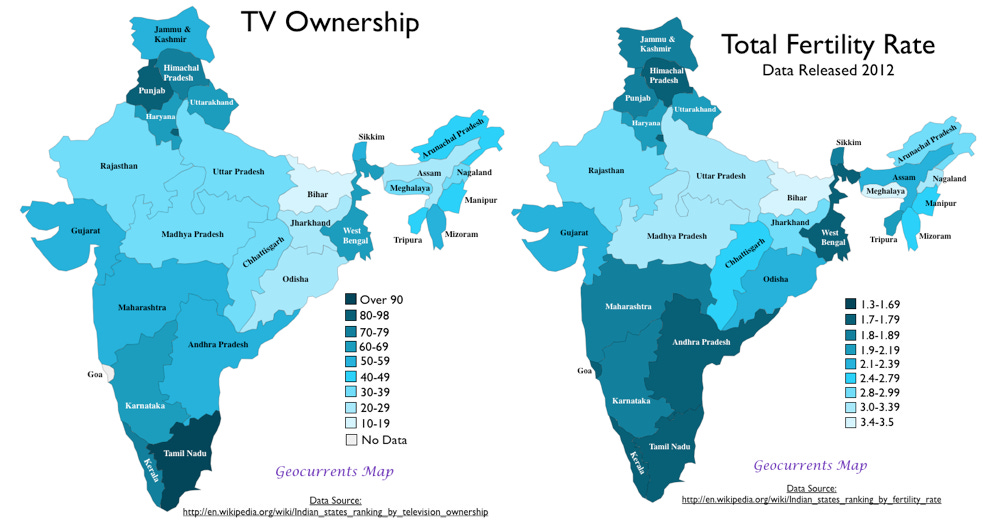

As geographer Martin Lewis shows, maps of television ownership and fertility rates in India look strikingly similar. The correlation isn’t perfect, but it’s telling: when time, information, and opportunities change, family decisions change too.

The Bottom Line

Economists think in trade-offs because treating choices as free leads to poor policy and misplaced blame.

Shonda Rhimes wasn’t failing at motherhood or work; she was navigating constraints. The guilt she describes is one many of us feel every day. Families today aren’t rejecting children; they’re responding to rising costs, limited time, and competing demands. When millions of people face the same constraints, personal trade-offs aggregate into social trends.

And this isn’t only about how we spend our time, it’s about how we spend our dollars. It’s about taxes, subsidies, and the incentives we create through policy. It concerns which costs we socialize and which we leave to individual families. Childcare, housing, healthcare, and work flexibility don’t just reflect values; they shape trade-offs.

If we want different outcomes, we need to understand the tradeoffs at work.

Further Reading

From Amazon

In The Two-Parent Privilege, Melissa S. Kearney makes a data-driven case for marriage by showing how the institution’s decline has led to a host of economic woes—problems that have fractured American society and rendered vulnerable populations even more vulnerable. Eschewing the religious and values-based arguments that have long dominated this conversation, Kearney shows how the greatest impacts of marriage are, in fact, economic: when two adults marry, their economic and household lives improve, offering a host of benefits not only for the married adults but for their children. Studies show that these effects are today starker, and more unevenly distributed, than ever before. Kearney examines the underlying causes of the marriage decline in the US and draws lessons for how this trend can be reversed.

Kearney’s research shows that a household that includes two married parents functions as an economic vehicle that advantages some children over others. For many, the two-parent home may be an old-fashioned symbol of the American dream. But this book makes it clear that marriage may be our best path to a more equitable future. By confronting the critical role that family makeup plays in shaping children’s futures, Kearney offers a critical assessment of what a decline in marriage means for an economy and a society—and what we must do to change course.

Fertility vs Birth Rate is a labeling issue. Fertility captures within a specified age-range (reproductive age) whereas Birth-rate captures a population as a whole. Education, Birth control and establishing professional standing affect fertility. Add those and any other statistic as a reason for the population rate to change.

Leaving the "We're no longer an Agrarian Economy" aside, the average age of a person in the US is 37. 10 years higher than a generation ago. (Immigration changes will push this upwards in the near term before we rebalance.)

Rhimes, Sandberg, etc are all just addressing Preception Bias carrying forward something Fisher wrote in the 80's, "Getting to Yes". For them adding in gender roll biases but downplaying income disparities that elevate their ability to resolve certain daily issues, is about them addressing guilt. It's public self-soothing promoting societal changes that have been occurring since the 70's.

The choices we make, in turn, make us. Control is an illusion.

So many things...

First: YES! Shonda is right. I have also seen this.

Second: Shonda -- and I -- are in positions of privilege -- we have the ability to take advantage of more expensive yesses, harder to access yesses. I took a summer in Europe when I was in college. It was not that expensive -- I bought a Eurailpass and slept in youth hostels and ate a lot of bread and cheese -- but I did not have to work (I had saved money working at the local department store in high school -- but I also did not have to spend that money on clothes and food & cet). Shonda can say yes to being on TV -- I said yes to acting in a play with my daughter at a local community theater, which I felt not too nervous about, because I had done a ton of theater in high school and college -- 30 years previously, before life happened. See what I mean? Not everyone can say yes to everything. No, you really cannot do whatever you want. But you definitely can leverage what you have, and turn that into more! And you never know where that can lead -- maybe to life satisfaction.

Oh -- TV and fertility... You understand what happened, right? What was it on the TV that changed all those women's lives? IT WAS THE SOAP OPERAS!!! I am not kidding at all. The most watched programming in Spanish in the two American continents are Mexican soap operas -- this, by the way, is why Mexican Spanish can be understood everywhere in the Americas. Exactly the same in the Arab world with respect to Egyptian soap operas -- which is why Egyptian Arabic, which is not at all universal in the Arab world, is nevertheless universally understood. And of course all the conservative clerics rail against it, and no one listens. Same with Hindi soap operas in India, Nigerian soap operas in large swathes of Africa, and of course US ones in English. Women become obsessed with the lives of these free, upper class women, and they want to have that ability to work and have a meaningful life outside the home, freedom to make decisions, etc. I hope this does not let the secret out, and inspire a generation of socially controlling dictators to change the format. China is a warning of what happens when they do. Chinese state TV is hopelessly boring (like Soviet TV was too), and no one watches it willingly (in the USSR the TV was required to be on all the time, and so a generation of Soviets grew up able to filter out the background noise of propaganda and pap). But currently there is a huge surge in independently produced 2-minute soap opera segments that people watch obsessively alongside the modern Chinese busy stressful life.

One last thing: the domestic economy. I periodically get mad at how utterly the economics profession ignores household production. Yes, of course GDP primarily follows commercial production, as it should -- Kuznets initiated this industry in 1934 to see how well the US economy was recovering from the Great Depression (badly). But we do not have solid date on what households produce. I'm not talking about making meals and cleaning and fixing things -- the BEA does a pretty good job on this (here: https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/household-production). I mean the PURPOSE OF HOUSEHOLDS, which is sexual services, companionship services (there is a market price for this in Japan. No, I'm not kidding), quality parenting. Like: by how much is income over a subsequent lifetime improved by high quality vs average parenting services, net of education and income? Nobody knows. If anyone out there has a graduate student who wants to dedicate a career to teasing out such data, I'd love to hear the results.